laughter for the sake of heaven

Sholem aleichem,

Before we dive in, I wanted to let y’all know that I’m putting together an online chaburah (learning collective) to learn Rebbe Nachman's Elul Torah during Elul this year (starting in a month, on August 25th). Join us to learn about the process of perpetual repair, the two essential skills in a life of teshuvah, and what it really means to say the words "I am ready to become".

More info and sign-up: https://drive.proton.me/urls/QNT9BRDNE0#QDy6LIqp41GZ

Okay, so -

It happened once that the sages of Chelm were trying to bring a boulder down off of a hill. They all surrounded the boulder and were slowly dragging it down the hill. When they were about halfway down, a passerby interrupted them, “Rabosai, rabosai, surely it would have been easier to just push the boulder and let it roll down the hill?” The sages conferred, and agreed with this chiddush. So they dragged the boulder back to the top of the hill, gave it a push, and indeed! It rolled all the way down.

In a couple months, I’ll be three years sober, thank gd. I actually first got sober over nine years ago, sometime in the summer of 2016. It took me a lot of trial and error, over the next six years, to learn how to be consistently sober. As I’m reflecting on that process, I’ve been thinking about the feeling of “needing to get sober again”. The feeling of being back in a place I’d been before, and needing to start all over, from scratch.

Let’s open the Torah to Masei, the second of this year’s double-portion (Bamidbar 33:1):

These are the journeys of the children of Yisroel, who went out from the land of Mitzrayim, by their hosts, in the hand of Moshe and Aharon.

…They set out from Ramseis and camped at Succos

They set out from Succos and camped at Eisam

They set out from Eisam…and camped before Migdol

…

The Torah repeats the same words — “they set out…and camped” — over and over, a total of 42 painstaking repetitions.

So, my favorite prayer, since beginning my return to Yiddishkeit, is Ana b’Koach. I love all the melodies we sing it to, and I love the words. “Untie our tangles” I find myself singing, sometimes, all the way home from shul, “Oh knower of mysteries!”

Ana b’Koach is a short prayer, just 42 words. But it’s an important prayer, especially in Kabbalah: the first letters of the words of Ana b’Koach correspond to a secret 42-letter name for haShem, part of a tradition stretching back to (at least) the time of the Mishnah (Kiddushin 71a):

Rav Yehuda said that Rav said: the name of 40 and 2 letters, they did not transmit it except to one who is tznius and humble, and stands in half of zir days, and has no anger, and does not get drunk, and does not stand upon zir stature.

There’s a tradition that connects Ana b’Koach and the 42 letter name to the 42 journeys carefully listed in our Torah portion.

Earlier in Bamidbar, the Torah told us that the b’nei Yisroel traveled “according to haShem, by the hand of Moshe” (Bamidbar 9:23).

The Malbim explains, in the name of the Maharash, that “according to haShem” should be read literally: according to “ha shem”, that is, according to “the name” of 42 letters. “Each journey”, the Malbim teaches, “was indicated with a single letter from the letters of the name of 42.”

Ramseis, their first camp, wasn’t just Ramseis. It was also the first letter in the name of 42: an א. And when they set out from Ramseis, leaving the aspect of א, they journeyed toward the next letter in the name: a ב.

But there’s more than one camp in the journey that corresponds to the letter ב. The Malbim continues:

When you place in order the 42 letters of the name of 42, corresponding to the [42] journeys, you will find … the letter ב three times.

In Ana b’Koach, the Malbim points out, the letter ב appears at the beginning of three separate words: b’koach/in-strength (the 2nd word), barcheim/bless-them (the 19th word), and b’rov/in-great (the 27th word).

If we list out all of the camps in the journeys in order (and I did), we’ll find that the 2nd camp was Succos, the 19th camp was K’heilasah, and the 27th camp was Motseiros. So all three of these camps correspond to the letter ב in the name of 42.

This is the meaning of the second half of the verse “according to ha-shem, by the hand of Moshe.” Leaving Ramseis, they were directed “according to the name” toward the next letter ב. And it was Moshe our Teacher, peace be upon him, who understood which specific aspect of the letter ב needed to come next: strength/b’koach, corresponding to Succos; blessing/barcheim, corresponding to K’heilasah; or greatness/b’rov, corresponding to Motseiros.

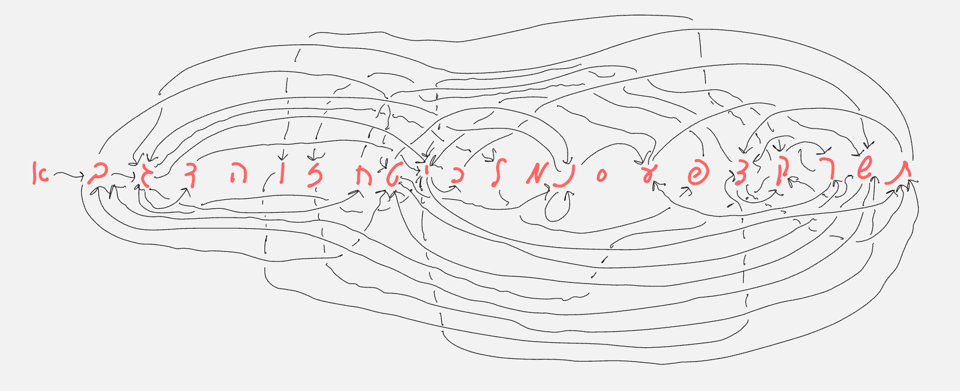

The journey in the wilderness, in other words, wasn’t a journey from one camp to another. It was a journey through the letters of the alef-beys, a journey that kept looping back on itself, returning over and over to the same letters: departing from Succos, the ב of b’koach, only to return, some time later in the journeys, to the ב of barcheim at K’heilasah.

I mentioned earlier the feeling of starting over from scratch with sobriety, of having circled back to a place I thought I’d left behind. But I never truly circled back. As I spiraled through the Name, letters changed form as I came and went. After leaving the צ of “trouble”, I returned to צ to find that it had become ”justice”, and then later, ”screams”; after leaving the נ of “please”, I returned to נ to find “lead [your people]” in its place.

There are some letters that the b’nei Yisrael return to over and over in their journeys. But they never return to א. They’re never back at the start, in any form.

The first time I had to get sober again, I wasn’t back where I started, either. Because at the start, I’d never gotten sober before. As soon as I was getting sober again, I had made my camp at a completely different letter of haShem’s name. That first step into the wilderness, the first time I got sober, caused a fundamental shift. Even though I wouldn’t stay sober from then on, even though I’d relapse again and again, something in me, something in my life, something in the Name was altered. Forever.

That word, again, contained in it all of my journey from first getting sober to the point of getting sober a second time. In the moment of deciding to try again, that part of my past could have helped me feel the change in the Name, despite my relapse. It could have helped me sense the newness of the experience before me, to get sober again. Instead, it felt (in the moment) like that past was made meaningless through relapse, just a challenging experience that I now had to repeat verbatim.

So, I started this dvar with a joke, learning from the model of our sage Rabbah in the Gemara, on Shabbos 30b:

Before opening [a teaching] with the Rabbis, Rabbah would say a word of cheer, and the Rabbis would be cheered.

The Baal Shem Tov explains (Kesser Shem Tov 37):

[On] the matter of "a word of cheer before the teaching". [This is] because life runs and returns, and a person is in the secret of smallness and greatness, and by means of joy and a word of cheer ze goes out from smallness to greatness to learn and to be joined with Voi, the Blessed

(using Voi/Void/Voix pronouns for haShem, as I learned from my teacher brin solomon.)

Elsewhere in the Gemara, in Taanis 22a, Eliyahu haNavi is telling Rabbi Beroka Khoza’a that the two brothers he sees in the shuk have a place in the World to Come. Rabbi Khoza’a asks them their occupation. And they say to him: “we are merry-makers”. The Baal Shem Tov explains:

"these two merry-makers" … would open the narrowness of a person by means of words of cheer, and then were able to bring zir close and lift zir up

This, the Baal Shem Tov explains, is what the Torah means when she says, in the Binding:

וַיִּקַּ֞ח אֶת־שְׁנֵ֤י נְעָרָיו֙ אִתּ֔וֹ וְאֵ֖ת יִצְחָ֣ק בְּנ֑וֹ

and [Avraham] took two of his lads [servants] with him, and Yitzkhak his son

The word שְׁנֵ֤י means “two of”. But vocalized differently, it could mean “years of”. And, with some flexibility, we can read נְעָרָיו֙ not as “his lads” but “his youth”.

So Avraham “took the years of his youth with him” — and his son, also. Yitzkhak, whose name means “he will laugh”.

The Baal Shem Tov explains:

Because by means of laughter for the sake of heaven, ze is able to lift up zir years of youth also with zir.

Through laughter for the sake of heaven, we can bring our past with us. Not as something that weighs us down, but as something that rises with us. Not in a sense of smallness and constriction, but in a sense of expansiveness and freedom. Because life runs and returns through the Name. And the life that we’re living? Is it not the Or Ein Sof, the light without end, the light that is gematria laughter?

We can’t always laugh, of course. And not all laughter is for the sake of heaven.

But it is funny, sometimes, truly. To be back at the top of a hill, dragging a familiar boulder behind me, realizing I could have just let it roll down from where I was before.

The view might look the same as it was the last time I was up here, but if I open up, something feels different. I’m somewhere new in the loops and spirals of the Name, between the א of “please” and the ת of “mysteries”. Maybe I can let the boulder go, this time, and watch it roll down the hill…

good shabbos,

ada

p.s. Here’s my full translation of the Malbim’s commentary explaining the maamar of the Maharash. It includes fun autobiographical tidbits about the Malbim! And a table of all the words of Ana b’Koach with corresponding camps! We love tables! We are nerds!

p.p.s. “and the life that we’re living? is it not the Or Ein Sof?” is a reference to the Meor Einayim, who said (see my dvar on Vayeishev for more on this):

אפילו כשהוא מצומצם אצליכם כשנפלתם ממדריגתכם אף על פי כן אתם דבקים בהשם יתברך באמצעות כי הלא חיים כולכם היום ומי הוא החיות שלכם הלא הוא יתברך שמו ויתעלה זכרו

Even when [the Blessed Name] is contracted from you, when you have fallen so far, even then you are so close to the Blessed Name, because are you not alive today? and who is your aliveness? is it not the One, may her name be blessed and remembrance raised?

p.p.p.s. The fact that “or ein sof” is gematria “laughter” comes, I believe, from R Yitzchak Meir Morgenstern. I heard it in a shiur that I can’t find from R Joey Rosenfeld.

p.p.p.p.s. I learned the joke about Chelm from the excellent collection “Yiddish Folktales” edited by Beatrice Silverman Weinreich and translated by Leonard Wolf. My version is probably a bit different at this point!

Add a comment: