Notes on (ballooning) stationary

A particular delight during the archival research for my book was the often-personalized stationary created by my protagonist and his correspondents. Though he is perhaps best known as a photographer, as his famous firsts make clear, Nadar is equally associated with aerial navigation. An early and ardent proponent of the flight of machines heavier than air (what we know as aviation), he nonetheless was deeply embedded in the culture of ballooning.

It is no surprise that balloonists figured prominently among his correspondents. Entrepreneurial spirits that they were, printed letterhead was an opportunity to tell a story and, hopefully, ensure some future opportunities. While aeronautic self-fashioning does figure prominently in the book (see chapter 2!), the stationary itself sadly does not. I couldn’t let these gems go unseen, so here are some notes on ballooning stationary from nineteenth century archives in Paris (primarily the Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris, for inquiring minds).

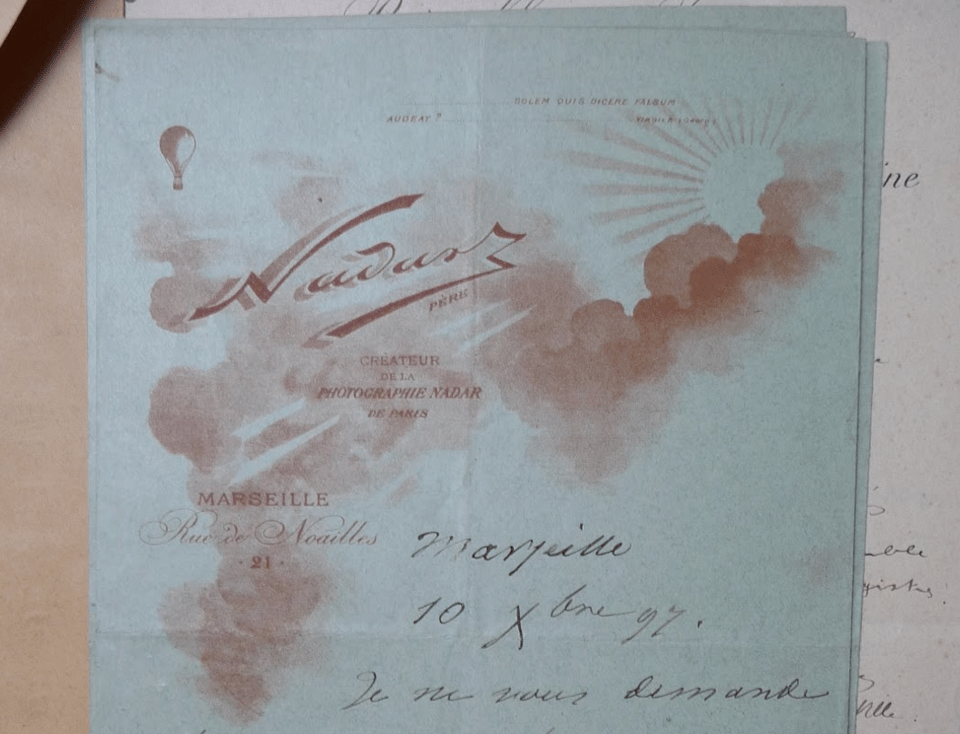

In 1897, forty-three years after its first incarnation on rue Saint-Lazare in Paris and with its patriarch at the age of 77, the sun had not yet set on the Studio Nadar. Emblazoned in red and floating in a bed of clouds, Nadar’s by-then iconic signature basks in the rays of a glowing sun. In keeping with his lofty personal iconography, a small balloon at left signals both Nadar’s lifelong devotion to the cause of aerial locomotion and the inflationary nature of his celebrity. Topping this aerial vista, a verse from Book I of the Roman poet Virgil’s Georgics reads “solem quis dicere falsum audeat?” [“who dare say the sun is false?”]. This phrase was regularly cited in nineteenth-century French photographic literature in order to stress the source and accuracy of what had, early on, been called heliography — literally sun-writing. In the passage from which this line is drawn, Virgil describes the possibility of forecasting the weather and intuiting or marking impending historic events through the interpretation of visual signs in the natural world. In the form of this soothsayer sun, Nadar offers a pithy reference to photography, the medium that had so profoundly shaped his career and the century in which he lived.

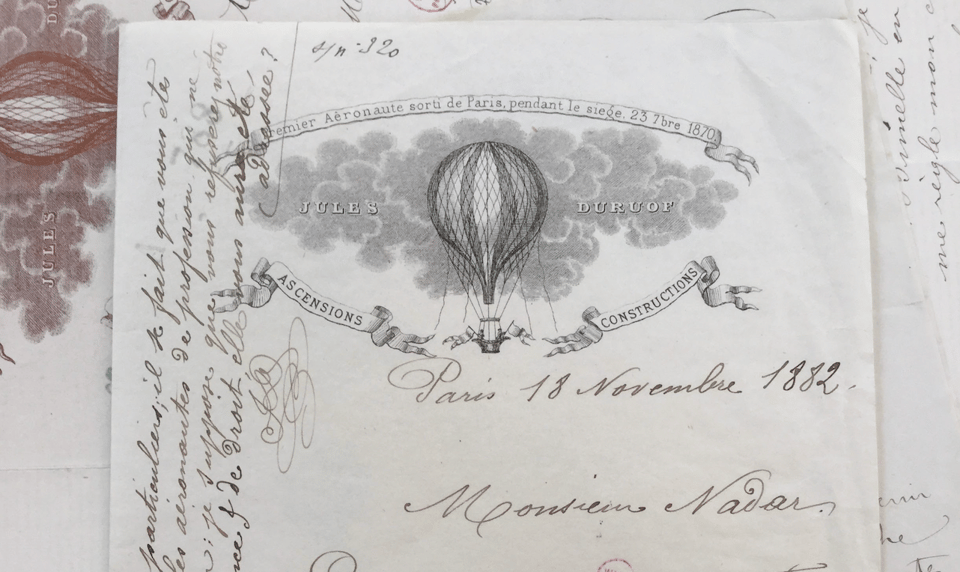

Like the surface of a photograph, the top of a letter was a space to stake a claim—a first. Here is a letter from aeronaut Jules Duruof, reminding us that he was the first aeronaut to make it out of Paris by balloon during the 1870 Siege of Paris. Not only did he shepherd the balloon Neptune out of the city over advancing Prussian lines, he brought with him several pigeons who would later fly back to Paris with written missives (more on this form of communication to come in a future letter).

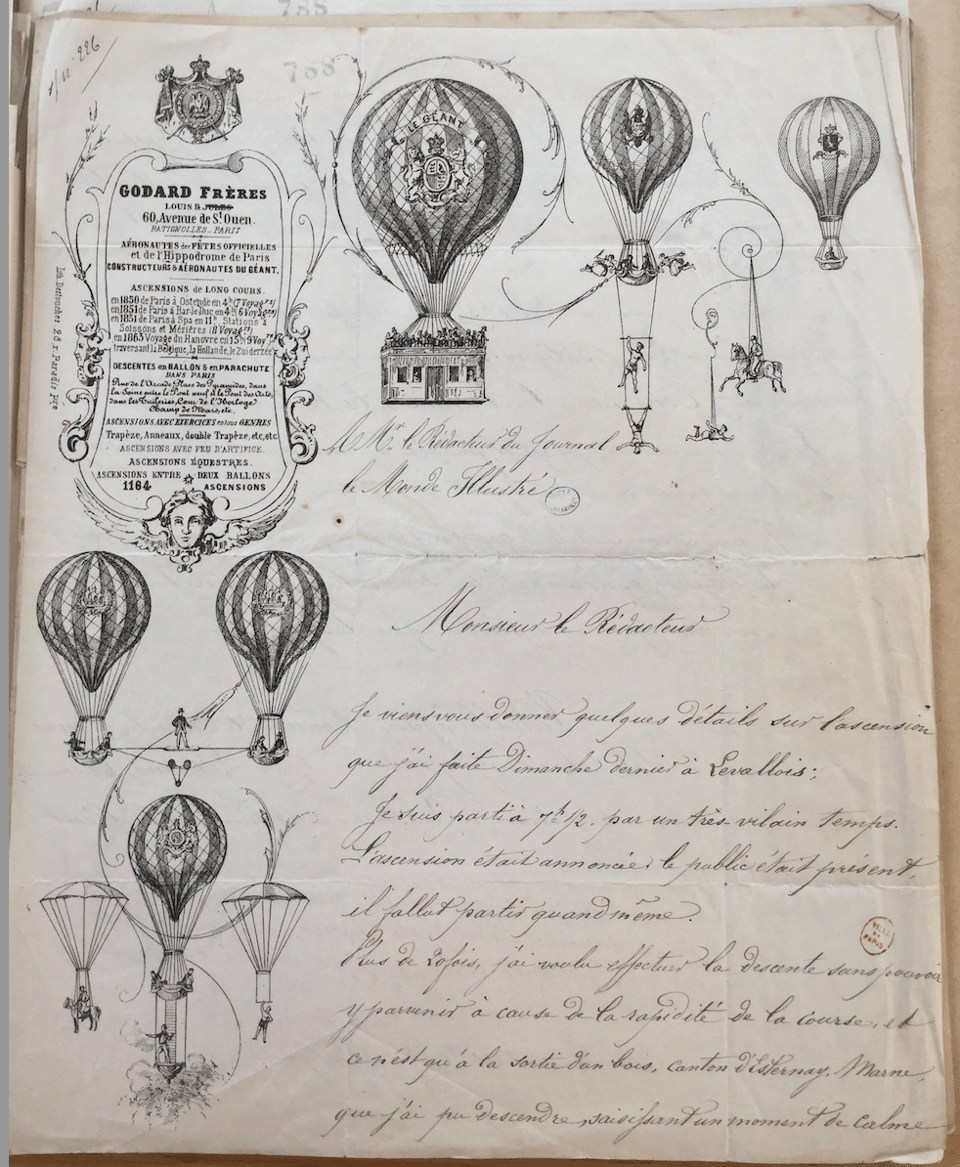

Ballooning — like photography itself — hovered somewhere between popular entertainment (or commodity) and scientific enterprise. The Godard brothers, Eugène and Louis, built and maintained several of the early hydrogen balloons that made successful flights in France. Eugène would later tour several of the balloons — including here in Montréal. Their letterhead listed these feats, among them building Nadar’s famous Le Geant (featured at centre left). On the blank surface of the page, the balloons make space for circus feats — flying horses, acrobats, and tight-rope walkers. The whimsical tendrils holding each body in flight point to ballooning’s oscillation between mass entertainment, speculative mode of transportation, and, it was hoped, lucrative commercial possibilities.

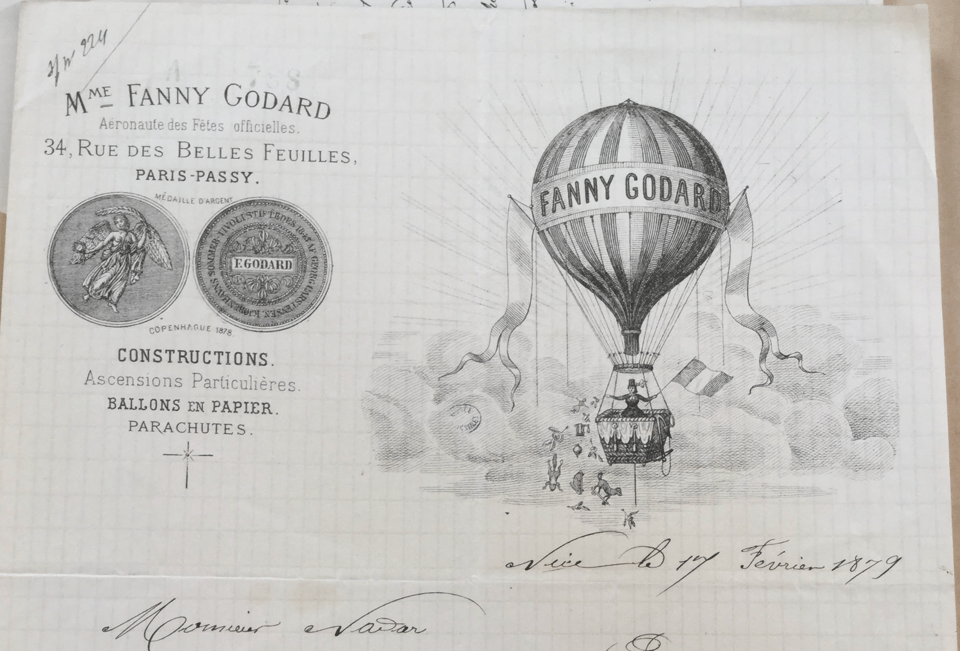

Though less common, women aeronauts were not to be left behind. Of the same Godard family, Fanny Godard asserts her own capacity for flight in her letterhead. Waving the French tricolour flag and positioned quite definitively as the master of her own aerial domain, Godard wrote to the Nadar studio in 1879 to hasten them to send her copies of the photographic portrait they had made of her en ballon.

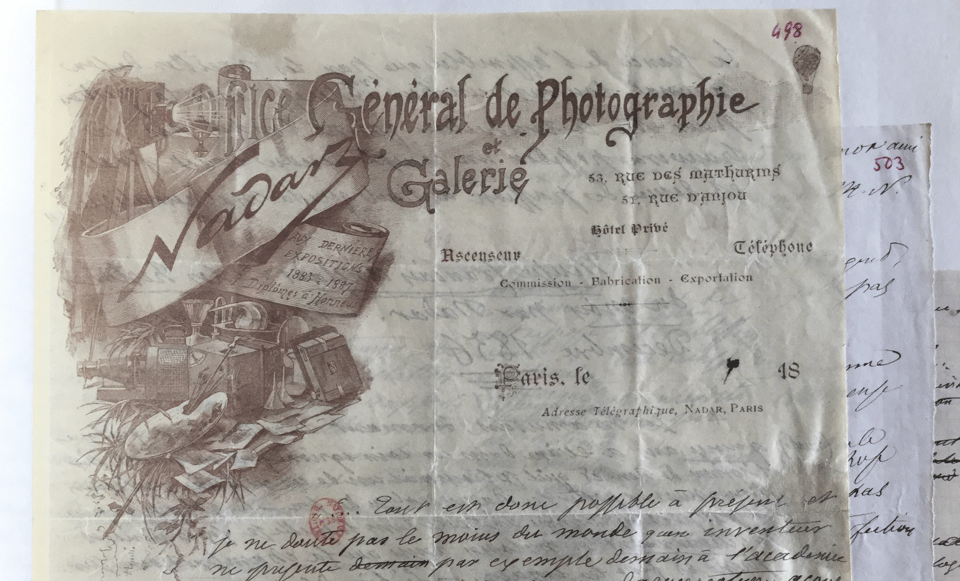

5. Over the course of the many decades of its existence, the Nadar studio never failed to make its association with early ballooning known. Even in the letterhead for Nadar’s son Paul’s Office général de photographie a small balloon floats off in the top right-hand corner — a miniscule yet iconic reminder of the centrality of ballooning to Nadar’s reputation and celebrity.

I could go on but I’ll stop myself there. More archival outtakes to come! Until then, have you ordered your copy of the book?

Sincerely,

Emily

P. S. Have you ever bought special writing paper? Received a letter on wonderful stationary? I want to hear all about it. Hit reply and tell me your epistolary stories.

P. P. S. Did someone forward you this letter? Hit subscribe below to receive notes from me in the future.