new year, new book, old questions

Dear reader,

Writing a book is a strange thing. A smart friend asked me over dinner recently: why did you write a book?

I’m not sure I know the answer but if it did it would go something like this.

Somewhere around 2012, I became obsessed with a series of photographs of model helicopters by a nineteenth-century French photographer named Félix Tournachon — known simply as Nadar.

As I continued work on this project, people (read art historians) regularly seemed confused as I stated my project’s focus. Nadar? Everybody knows who he is.

The assumptions held in this sentence quickly became an object of fascination — was art history (or history in general) a process of filling in gaps of previously unknown knowledge? Once something “was known” (to whom, I wondered) could it never be reinvestigated?

Nothing I knew about art history would indicate this was true — books on Manet or Degas abound. Yet for some reason, when it came to Nadar: a singular focus on a well-known artist was, it was made clear, somehow old-fashioned or, worse, conservative.

And yet, most of the stories told about Nadar, were, it became increasingly clear, just that: stories. So where did they come from and why did they bear repeating?

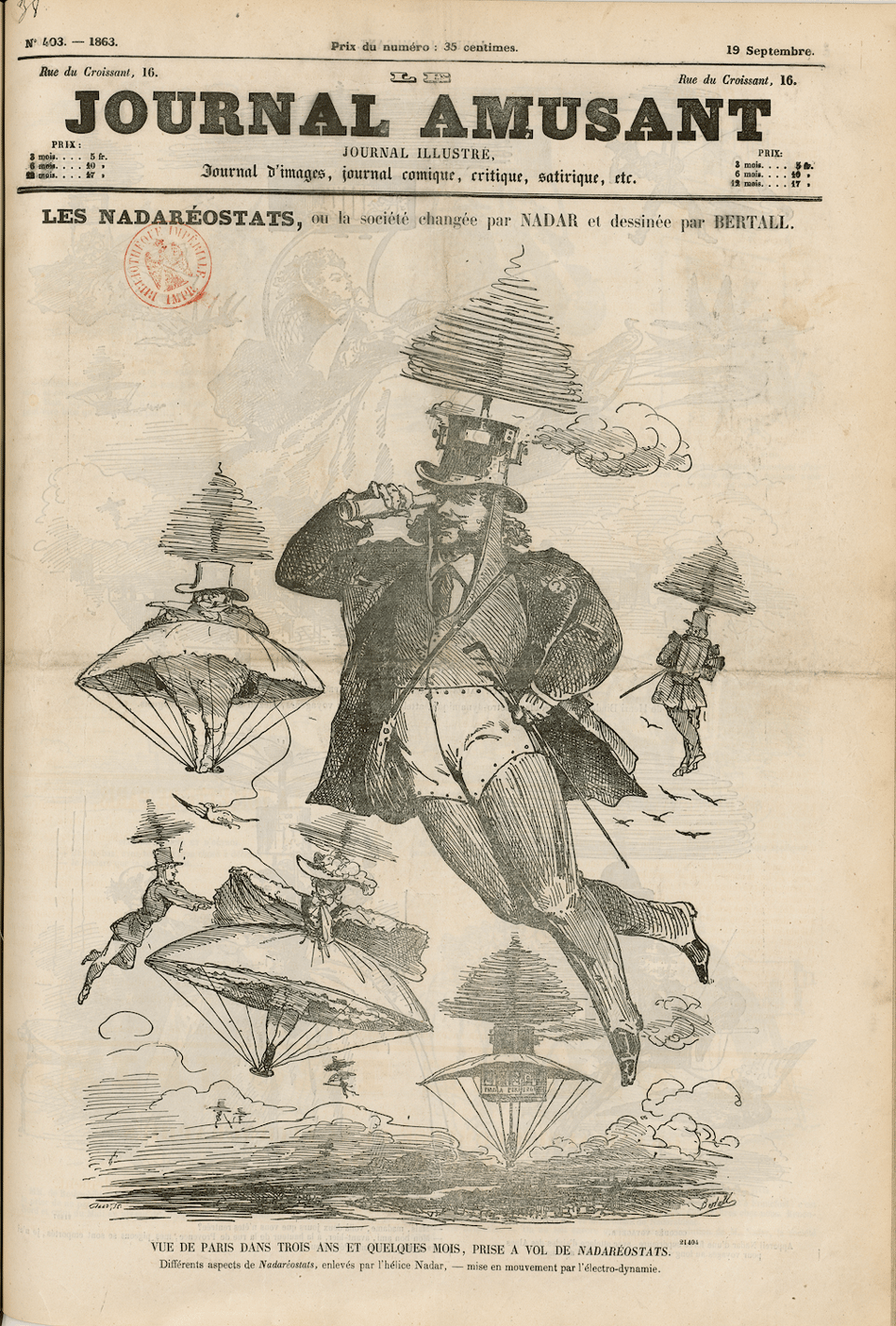

When I wrote this all up as a PhD dissertation, I argued that these stories were a process of speculation, an attempt to bring about a certain future (see the Nadaréostats below).

Nadar, like so many of his nineteenth century compatriots desperately wanted a different world, while for some that meant a world in which the working classes held collective power, for others that meant air ships in the sky — and for some, it meant both. In this rendition of the story, Nadar’s tall tales and speculative visions were a process of imagining a future into being.

When I returned to this project to rethink it as a book, I somewhat suddenly realized I’d been quite wrong — or actually, right, but about the wrong thing. The story was so much more mundane, though all the more useful (historically speaking). Where, hopped up on “socio-technical imaginaries,” I’d previously seen speculation, I now saw archives.1 What I’d interpreted as a process of future-making was also a process of legacy-making — yet another category of the future. The tenor of my analysis shifted towards understanding the process of representing “innovation” as a self-branding process rather than as a way to imagine the future in and of itself.

The question then became more nuanced: how do images (or, perhaps, media, more broadly) of the technological present shape the history of technology of the future? Or more simply: how is the new pictured, and therefore remembered? And, more importantly for my protagonist, who will be remembered as the author/inventor of that future?

In the resulting book I’ve largely tried to avoid making connections to the present, but there are no historians outside of their own situation. To say that my thinking on this has been influenced by the intervening techlash and wholesale ”enshittification” of contemporary technology is probably an understatement. And yet, I remain a citizen of the twenty-first century writing about the nineteenth — but why?

Put simply, because:

What has been will be again,

what has been done will be done again;

there is nothing new under the sun.1

I’m very excited (and slightly terrified) to say that the book is almost here. Now available for preorder, Inventing Nadar: A History of Photographic Firsts will be published by Duke University Press on April 21, 2026. Just a few short months away.

You can order a copy here. Use code E26NADAR for 30% off your order.

More soon friends,

Emily

P. S. What are you reading? What are you writing? Hit reply and let me know ;)

Ecclesiastes 1:9. ↩