The Ed's Up - Immersion in the True Reality

Last month, I wrote a piece for the New York Times about what birding has meant to me. Here’s a little snippet, but you can read the full piece with this gift link.

Birding has tripled the time I spend outdoors. It has pushed me to explore Oakland in ways I never would have: Amazing hot spots lurk within industrial areas, sewage treatment plants and random residential parks. It has proved more meditative than meditation. While birding, I seem impervious to heat, cold, hunger and thirst. My senses focus resolutely on the present, and the usual hubbub in my head becomes quiet. When I spot a species for the first time — a lifer — I course with adrenaline while being utterly serene.

When I step out my door in the morning, I take an aural census of the neighborhood, tuning in to the chatter of creatures that were always there and that I might have previously overlooked. The passing of the seasons feels more granular, marked by the arrival and disappearance of particular species instead of much slower changes in day length, temperature and greenery. I find myself noticing small shifts in the weather and small differences in habitat. I think about the tides.

It’s easy to think of birding as an escape from reality. Instead, I see it as immersion in the true reality. I don’t need to know who the main characters are on social media and what everyone is saying about them, when I can instead spend an hour trying to find a rare sparrow. It’s very clear to me which of those two activities is the more ridiculous. It’s not the one with the sparrow.

I originally wrote the essay for this newsletter but offered it to the Times at the last minute. I’m glad I did; it undoubtedly reached more people, and the response has been heartwarming. One friend told me that it helped her finally understand why people bird. Another is inspired to take it up. And while the piece is ostensibly about birding, it’s also about deliberately carving out space for joy and attention in one’s life. One reader said that it had helped him reconnect with a part of his childhood that he had lost, and was now keen to share with his own kids.

In hindsight, there’s so much I didn’t mention. Especially now, when so much of the world feels like it’s spinning out of control, there is something quietly radical about spending a lot of your day looking up: My neck lifts; so, too, my spirits. They also do so in company. I was one of several dozen birders who recently went to see a Cassin’s sparrow that had somehow ended up in Berkeley. A bird of southwest grasslands, this species had never been recorded in the East Bay before, and though drab (even for a sparrow), we gawped at it like we were watching a total eclipse, relishing in both its unlikely presence and each other’s communal joy.

I also want to highlight this paragraph in the NYT essay:

So much more of the natural world feels close and accessible now. When I started birding, I remember thinking that I’d never see most of the species in my field guide. Sure, backyard birds like robins and western bluebirds would be easy, but not black skimmers or peregrine falcons or loggerhead shrikes. I had internalized the idea of nature as distant and remote — the province of [wildlife] documentaries and far-flung vacations. But in the past six months, I’ve seen soaring golden eagles, heard duetting great horned owls, watched dancing sandhill cranes and marveled at diving Pacific loons, all within an hour of my house. “I’ll never see that” has turned into “Where can I find that?”

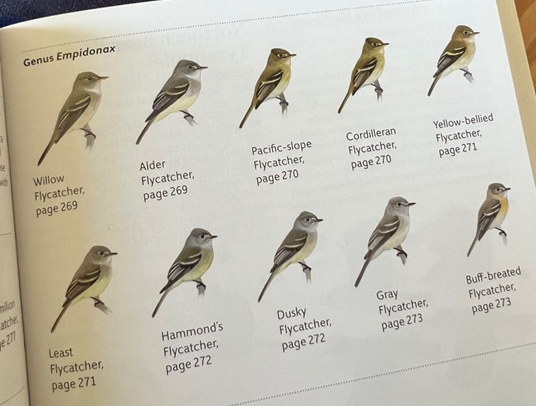

The mental block that I mention here is substantial and multi-faceted. It makes nature seem not only distant but hard to learn about, and there’s a quick leap from finding something daunting to dismissing it as pointless and dumb. Consider this page from my Sibley field guide:

Eight months ago, I looked at this and laughed. Those are all the same bird! I can barely tell them apart from the pictures, let alone in the field, with suboptimal lighting and branches in the way. Learning to differentiate them seemed impossible, and laughably so. Birding! How ridiculous!

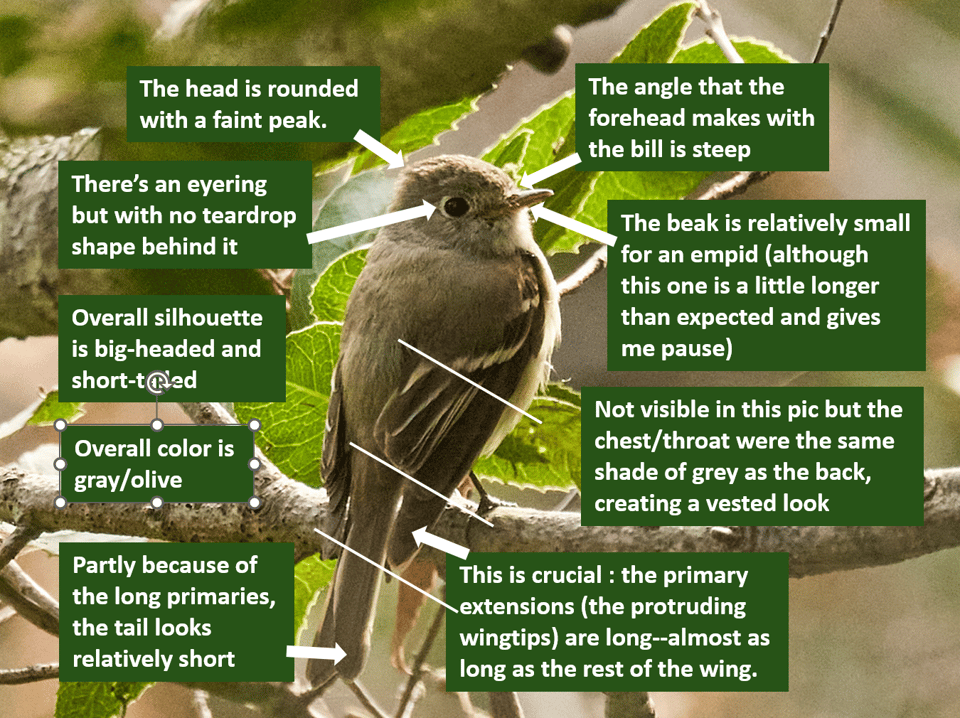

But then I started browsing All About Birds, a site from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, has detailed descriptions of every North American bird and, crucially, comparisons that show photos of similar species side-by-side along with marks that might distinguish them. The lab’s Merlin app has recordings of each species singing and calling, which I listened to. I watched this enormously helpful video (and plan to get the book by the same people). And after all that, earlier this week, when I saw the bird below, I recgonized it as a Hammond’s flycatcher.

Because while I might once have looked at that bird and seen a small grey thing with some white wingbars, here’s what I see now:

I’m about 90% confident about this, and ran it past three other birders to check my hunch. Hammond’s is probably one of the easier species to identify, and I’m still uncertain if I could pin down, say, a dusky flycatcher in the field. But my point is that it’s doable. There’s nothing stopping anyone from learning this, other than the perception that it’s impossible or pointless, when it is neither. To me, this kind of knowledge feels like being gifted with a precious secret—a way of better appreciating the living world, including the identities of its citizens, simply by looking and listening a little more closely.

Some Gugg news

I’m proud to say that I was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship—a long-running and prestigious grants scheme for people who show “outstanding aptitude for prolific scholarship or exceptional talent in the arts”. The money will help me to cover a lot of the reporting and travel for The Infinite Extent—the book I’m currently working on, about life at different scales.

Wildlife photography

Reading about Gaza and more

As usual, here are some pieces worth reading about Israel’s ongoing, US-funded genocide in Gaza.

“Mom quickly went out and stood in front of it, exactly in its path, and started telling them that there were civilians, women, elderly, and children in the house. The bulldozer kept coming.” A 14-year-old Palestinian girl named Lujayn describes the fourth time she has been displaced since Israel began assaulting Gaza.

The story of Gaza’s destruction in 100 lives—an incredible art piece by Mona Chalabi (who was also interviewed about her work here)

“I am old enough to remember when our public conversation was preoccupied with the coddling of college students, their unwillingness to confront hard truths and their desire for safe spaces, shielded from challenging ideas. Many of the voices who for years ridiculed the safety concerns of Black, brown, Indigenous and queer students are notably silent as an iron-fisted university leader sends in cops in riot gear to arrest college students for passionately engaging with political life and taking a stand on an important moral issue.” Lydia Polgreen on the campus protests, and the hypocrisy of the cancel-culture debate.

“This is, of course, the point of the meta-coverage of the raging protest movement: to drown out the protesters’ actual demands… as well as what is actually happening with U.S. money and materiel in Gaza.” Jonathan M Katz calls for some perspective on the discourse around pro-Palestine campus protests.

“It can be almost impossible for Palestinians to rid themselves of a looming sense of transience, whether they live in the diaspora or are struggling to hold on to their homes in the occupied territories. Imagine what it feels like to be a refugee in your own homeland.” Iman Fayyad on houses and homes.

And on other topics: Sabrina Imbler on the ethics of attempts to resurrect extinct species; Lindsay Ryan on how much of American health-care is really dealing with “end-stage poverty”; and Jenny McKee on the birding club for long-haulers that I founded.

Book recommendations

The Light Eaters, by Zoe Schlanger. If you read my last book and thought, “But what about plants?”, then this is the book for you. Instead of trying to ram the square peg of botanical life into the round holes of human biology and metaphors, Schlanger instead considers plants on their own terms, as they actually are. The result is mesmerizing, world-expanding, and achingly beautiful. I’ll be talking to Zoe about the book at Point Reyes Books on May 11.

Stories are Weapons, by Annalee Newitz. A thoroughly researched and masterfully crafted account of the past and present of psyops, disinformation, and propaganda. Newitz also gives us something hopeful—a way to disarm the narratives that have been used against us and reclaim better ones.

Future speaking events

I’ll be talking about An Immense World unless otherwise stated. Come say hi; please wear a mask

Apr 29 – Pittsburgh Arts and Lectures in Pittsburgh, PA (virtual ticket also available)

May 10 - UC Berkeley, a conversation with Donna Haraway

May 14 – The Cabin in Boise, ID

That's it for this week

As always, this newsletter is free, but you can choose to pay a monthly subscription (at whatever level you set) if you'd like to support my work.

Stay safe.

One more thing…

I spent so much time trying to find a pileated woodpecker that had set up shop in Sunol Regional Wilderness. I finally found it on a distant telegraph pole, which led to perhaps my favorite bird photo of the year. Note: there are still enough field marks to identify the bird here.