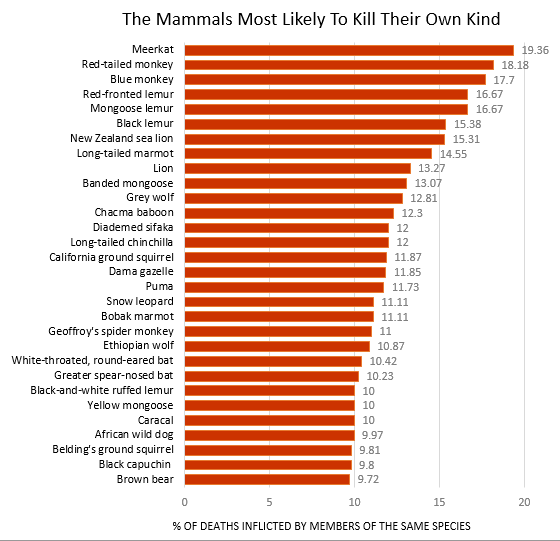

Chinchillas, man. Who knew?

If you're wondering about humans, look below. And if you're wondering about this particular, non-murderous human, here's a list of book talks I'll be doing over the next month:

"The point of this macabre census was to understand the origins of our own behavior. Gómez noted that closely related species tend to show similar levels of lethal interpersonal violence. He could use those similarities to predict how violent any given mammal should be, and whether it meets, exceeds, or defies those expectations. Humans do all three. Gómez’s team calculated that at the origin of Homo sapiens, we were six times more lethally violent than the average mammal, but about as violent as expected for a primate. But time and social organizations have sated our ancestral bloodthirst, leaving us with modern rates of lethal violence that are well below the prehistoric baseline. We are an average member of an especially violent group of mammals, and we’ve managed to curb our ancestry." (Image: Stefan Huwler)

Here’s a prediction. In the next month or so, a viral video will start circulating around the internet, depicting a mysterious underwater… thing. It will be a gelatinous specter appearing in front of confused divers, or a blobby phantom floating before a remotely controlled submersible, or a deflated lump washing up on a random beach. It won’t conform to your mental image of any animal; it probably won’t look like an animal at all. You, like most other people, will be confused. Even scientists, the headlines will claim, will be baffled. Except Steven Haddock. He will not be baffled. (Image: Lars Plougmann)

"We know that the bacteria in our microbiome are important for our health, and that changes in the microbiome have been linked to many conditions including inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, diabetes, and more. So it should be possible to improve our health by taking the right microbes. The problem is that we do so in a crude and naïve way. These areliving things and we are ecosystems. You can’t just introduce the former into the latter and assume they’ll take hold. You need to know why they might succeed or fail." (Image: Eric Gaillard)

More good reads