A Globe Gazing Upwards, A Little Less Bulky, A Commitment To One Another

Hello friends. My name is Duncan and this is Hello From Duncan, a newsletter that I usually send every ten days but haven't actually sent since the middle of August. As ever, it's free to receive and you're getting it because you signed up for it. There's an unsubscribe link in the footer if you need one.

The reason why it's been about six weeks since you last heard from me is threefold. First, because I went to the UK for two weeks (by train for the first time). Second because I got COVID on the way back, and third because despite testing negative for a week or so, I've been struggling with energy levels since. But I'm gonna try to get back on schedule, even if the next few newsletters are a little less bulky than they sometimes are.

In fact, you can expect fairly light newsletters for at least another month or so because I'm gonna be moving! To Malmö! I think I wrote earlier this year that we were looking for an apartment there, and we've finally found one. It's in an amazing part of town packed with fun stuff to do, it's two minutes from a big train station, and it's less than ten minutes from one of Malmö's bigger parks. I am extremely excited. We get the key to the new place tomorrow, and the moving vans arrive in a few weeks. So yeah - exciting times, but it may continue to curtail my newsletter-writing ability for a while longer.

Either way, the good thing about there being such a big gap between the last issue and this one means that there's a tonne of good stuff in here for you to dig into. So take your time with this one, don't feel like you need to read everything, and if any of it sparks any thoughts in you that you'd like to share, then please just hit reply.

As noted above, my trip to the UK this year was by rail for the first time. I thought it might be worth talking about how I did it, in case you'd like to do such a thing.

The journey takes about a day and a half. On the way out, I took an early train from Helsingborg to Copenhagen, then from Copenhagen to Hamburg, then Hamburg to Köln, then Köln to Brussels. I stayed overnight in a cheap hotel near Brussels Midi station, then got the Eurostar fairly early the next morning. With a little assistance from timezones, I was at my parents' house in Reading by 11am.

On the way back, I took at Eurostar mid-afternoon from St Pancras to Brussels, then an onward train to Köln. I stayed overnight in Köln and then got a direct train to Hamburg, another to Copenhagen, and then a final leg back to Helsingborg, arriving fairly late in the evening.

Neither journey was totally smooth. On the way out, there was engineering work around Köln that meant I had to get off at one small station, take a local train to another small station, and then get on another. All these trains were delayed quite substantially and while it worked out, it never felt at any point like it would. It was rather stressful.

On the way back, my calm evening train that was supposed to get me into Köln by about 8pm got stopped in Liege due to signalling issues, and then we had to wait around for about 90 minutes for a local train that then took us to a bus, which took us to another train. I eventually got into Köln a little after midnight.

The weak link in this chain seems to be Germany. I've written before in this newsletter about German trains and how they fail to live up to their reputation of efficiency. Quite honestly, they're unreliable as hell. But it's more or less impossible to get from Scandinavia to anywhere else in Europe without passing through Germany, so I'm gonna have to live with it. Luckily, Deutsche Bahn's system for getting refunds is pretty efficient.

My advice: for trains passing through Germany, make sure the connection you're trying to get to is not the last one of the day (so if you miss it you can get the next one), and consider also buying a five-euro seat reservation on the next connection if it's looking in any way shaky that you'll make it. It's a cheap insurance policy.

Also a bit of good news - Deutsche Bahn has pledged a huge modernisation of its network, investing about 40 billion euros over the next five years or so, paid for through greater tolls for foreign HGVs on the country's motorways. In the short term, this will mean even more disruption - major routes shutting down for months at a time. But once the work is complete, it should be better for everyone. Can't wait.

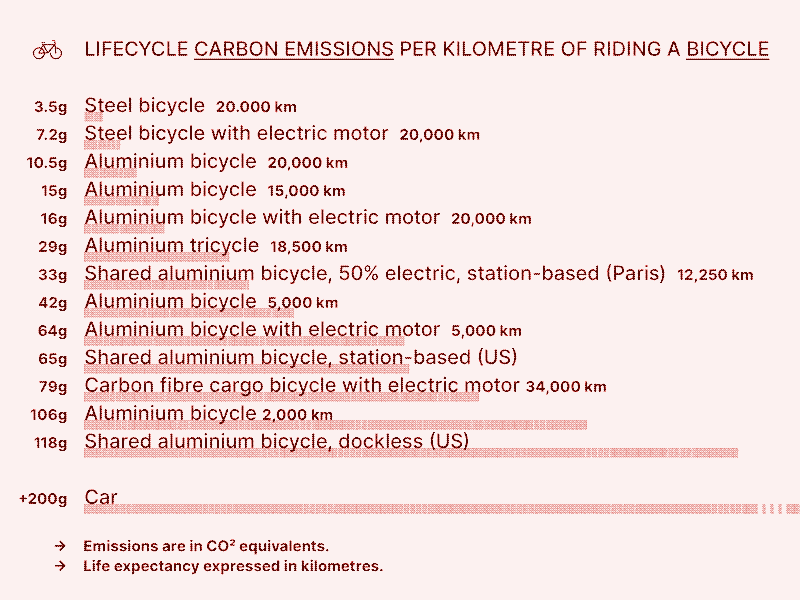

Low Tech Magazine, which has a solar-powered website, has published a good article about how bicycles are getting increasingly unsustainable. Obviously they're still a far better choice than a car, but if you're in the market for one then they recommend that you opt for an older, second-hand, steel-framed model. Here are the lifecycle emissions for several of the options:

And here's a good bit about what drives sustainability when it comes to bicycles:

For a long life expectancy, some parts of a bicycle need replacement. These are typically smaller parts such as shifters, chains, and brakes. Until a few decades ago, component compatibility was a hallmark of bicycle manufacturing. My bicycles are a perfect example of this. Most components – such as wheels, gear set, and brakes – are interchangeable between the different frames, even though every vehicle is from another brand and year of construction. Component compatibility allows for easy maintenance and repairability, thereby increasing the lifetime of a bicycle. Bike shops in even the smallest villages can repair all types of bicycles using a limited set of tools and spare parts. Cyclists can do minor repairs at home.

Unfortunately, compatibility is hardly a feature of bicycle manufacturing anymore. Manufacturers have introduced an increasing number of proprietary parts and keep changing standards, resulting in compatibility issues even for older bicycles of the same brand. For example, if the shifter of a modern bike breaks after some years of use, a replacement part will probably no longer be available. You need to order a new set from a new generation, which will be incompatible with your front and rear derailleur – which you also need to replace. For road bikes, the change from cassette bodies with ten sprockets (around 2010) to cassette bodies with eleven, twelve, and most recently thirteen sprockets have made many wheelsets obsolete, and the same goes for the rest of the drivetrain including shifters and chains.

Read the whole thing here.

I really appreciated Max Patrick Schlienger's article on "The Cargo Cult of the Ennui Engine" (that link goes to a version I highlighted so you don't have to read it on Medium and deal with their paywall, but you'll find a link to the original in the top right).

I found a lot in it that I identified with, like how I default to scrolling feeds when I have a free moment, rather than picking up a book or an instrument or a movie I've been wanting to watch for months.

We scroll through Twitter, Facebook, TikTok, and Reddit, vaguely hoping to find something with which to amuse or inform ourselves before getting up in the morning or going to bed at night. We favor videos that either are very short or don’t require dedicated focus, confident in the knowledge that we can move on to something else whenever we want to. We ignore thoughtfully composed “walls of text,” but we electronically applaud memetic image macros and single-sentence references that aren’t inherently entertaining or insightful (yet are somehow still poorly written).

It covers a lot of ground, from cargo cults, to emotional energy, to the ways in which the human brain is "not so different from that of a pigeon". It's great. Give it a click.

Way back in 2015, eight years ago(!), I curated a series of themed article collections for How We Get To Next - a publication about how the world is changing. It was just as the current AI acceleration was getting started, and it's fascinating to see some of the perspectives we held then.

One of my favourite articles that I commissioned was from my friend Matt O'Leary, who wrote about his experiences using an AI-powered recipe app that dictated everything he ate for a week.

You know, it was actually a really good dish. I was at first unsure–the basil seemed like a bit of an afterthought; I wasn’t sure the lime zest was necessary; and cold salmon salad on a burger bun isn’t really an easy sell. But damn it, I’d make that sandwich again.

It's still a hugely fun read.

A few years back, I produced a data visualization cataloguing the canine cosmonauts of the Soviet Union. You've undoubtedly heard of Laika, the first animal to orbit Earth. You might have heard of Belka and Strelka, who were the first to reach orbit and return safely. But there were tonnes more, many of whom flew multiple times, and most of whom went on to live long happy lives back on solid ground.

France, though? The French sent a cat. A Parisian stray named Félicette flew on a sub-orbital rocket in 1963, and survived the trip, despite landing with her capsule upside-down and her bottom suspended in the air. But two months later she was put down so that French scientists could study whether she suffered any anatomical or physiological damage.

They later concluded that they had learned nothing of any use from the autopsy. No more cats were put into space, and France never launched its own astronauts. However, Félicette is still remembered. A statue of her, sitting on a globe gazing upwards, was erected at the International Space University at Strasbourg in 2019.

Lots more detail on Félicette, and various other animals that have been sent to space, right here.

Speaking of space, the Guardian also has a nice article about what's going on on the International Space Station, where (human) cosmonauts from Russia and astronauts from the West are required to cohabit for months at a time. The space agencies are saying nothing, of course, but the author interviews several former astronauts and cosmonauts - some of whom flew pretty recently - who have deeper insights. Meanwhile, Russia's space program is hitting the skids.

While America and its allies, and China on its own, forge ahead with new space stations, a return to the moon and ultimately Mars, Russia’s only real human space programme today is the 25-year-old ISS. That is one legacy of Putin’s terrible war. Sanctions and isolation have done the rest. The tech is ageing, the money is running out, the equipment sometimes defective. And the blows keep falling. Only last week Luna-25, the first Russian probe to return to the moon in almost half a century, crashed onto the surface just four days before an Indian probe landed there successfully. Within the last year, two Russian spaceships docked at the ISS experienced alarming coolant leaks in identical systems, suggesting serious production deficiencies on the ground. And, as I saw for myself in late 2019, the spaceport at Baikonur in Kazakhstan from where Yuri Gagarin launched into history in 1961 is visibly decaying, with its faded Soviet murals, crumbling buildings and stray dogs running wild. Once, the world marvelled at the nation that sent the first human being into space. But the world has moved on. The Russians talk about building their own space station or going to the moon or collaborating with China but, as Zak says: “The key word is talking. Russia has nothing. Russia has nowhere to go without the ISS.”

There's a recurring tendency for some folks to claim that technology is the solution to the climate crisis, that we'll magic our way out of it with human ingenuity. I'm sure I don't have to tell you that (a) that's implausible given the scale of change required, and (b) it's a risky bet even if it wasn't.

If you need some more convincing, though, then I'll refer you to this blog post which goes through the details of the various "technological antisolutions". Self-driving cars. Space colonisation. Burying trees. Geoengineering. Artificial intelligence. It's all there.

I propose that for something to be a technological antisolution, it must meet the following 5 criteria:

- It claims to solve a serious social or political problem.

- It is intrinsically incapable of addressing said problem.

- It is profitable under current market conditions.

- It further entrenches existing power structures.

- It is sexy.

It's a good post, go read it. However, it also made me realise two things.

First, that any company that makes money from selling climate solutions has a clear financial interest in prolonging the climate crisis for as long as possible.

Second, that I am one of those companies. I do a tonne of work around climate change, and if we solved the climate crisis tomorrow then I'd be out of a job. I can of course apply my skills to other areas, but a big reason why people hire me is my deep knowledge around climate topics.

Of course, that doesn't make me suddenly want to take up eating meat again, or to fly everywhere, or to buy an SUV. But it does make me think that I should probably have a plan for the possibility that we do somehow figure all this out.

For those among you of a certain age, this album made of MP3 compression artefacts is really quite something.

This is the longest article I have ever read about a bridge In Minneapolis that goes from nowhere to nowhere.

An excellent quote from the mayor of Pontevedra in Spain:

“It’s not my duty as mayor to make sure you have a parking spot. For me, it’s the same as if you bought a cow, or a refrigerator, and then asked me where you’re going to put them.”

From this Fast Company article.

Finally, I feel like I'm doing a lot of preaching to the choir when it comes to climate stuff. So I'll end with a short Rebecca Solnit essay on why that's a valuable thing to do.

Karen Stokes told me she thinks of the choir as providing a space that is the near opposite of the combative culture of the internet. “In so many churches that I’ve served, the choir is the primary support group. They meet every week; they hang out together, put in extra time on Sunday, have made a commitment to one another."

See you in ten days. I hope.

- Duncan