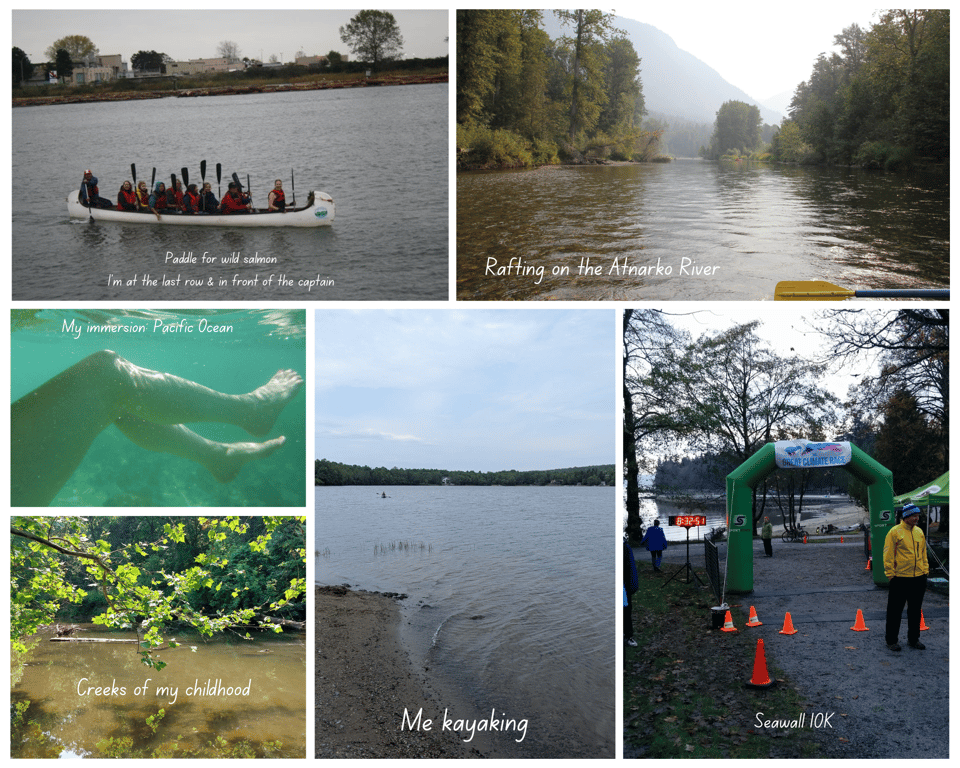

When kayaking recently, I found myself serenely navigating to the center of a lake. It was a hot day, and at the beach were sunbathers and picnics, at the pier were fishermen, and beyond the beach, was a little league baseball game. But here I wrapped myself in solitude. My partner and I are new at kayaking but have a lot of experience rafting and canoeing. That day on the lake, and a week before—dipping into the warm waters of Northumberland Strait—I recalled how much of my life has been in water.

Last summer, visiting family, I spent hours in the pool every day, lounging, swimming, immersed. I grew up in the Midwest, where I canoed and white-water rafted, or in the Chicago area, where I spent languorous afternoons at the Lake Michigan dunes, body-surfing, closing my eyes and dreaming while floating in the water. We spent summers at friends’ lake cottages, water-skiing, swimming, and drifting around in pontoon boats. In California, I tried to surf but never got very good at it, so I just body-surfed, swam, and boogie-boarded. In Oahu my husband and I stayed in the non-touristy area east of the North Shore, and our rusted cottage was on a private beach, so we spent hours in the water, just being.

For the last two decades, I’ve volunteered or worked with environmental organizations and spent my early Vancouver years raising awareness of wild salmon, managing beach cleanups, hosting an Earthwalk on coastal waters, paddling for salmon, even doing my first 10K on the seawall trail. I protested pipelines that would cross First Nations territories and introduce supertankers to the northwest coasts and channels. I studied the waters of the Great Bear Rainforest, wrote about them, rafted in them, and hiked through them. We spent an afternoon learning to sail a Viking longship and spent another day rafting the Squamish River, which is one of the most significant areas of wintering bald eagles in North America. Water is in my bones. I even loving running in the rain. It’s no wonder I’ve spent most of my life, including now, living near the ocean.

With water on my mind, I’ve decided to make a mid-summer newsletter with the theme of water and fiction.

Water and fiction/flashback

According to UN Water, an organization of international parties working on water issues, water is the primary medium through which we will face the effects of climate change. Warming temperatures in oceans means that species not capable of adapting will migrate or die out, which harshly affects ocean ecosystems. Water has become more scarce globally.

While facts are something we can and should pay attention to as we follow scientific integrity, models, and reports, another mode of telling the story about water has been alive forever: churned, spoken, and written by authors who dream up fictional stories related to our past, present, and future world. Where fact and fiction mingle like this is an area of reflection and speculation, tied by imagination. These tales of water ripple out once the pebble sinks in.

The quote above is by me, from an article I wrote for Climate Cultures titled Where Waters and Fictions Meet.

The books I listed in the article were:

Land-Water-Sky (Ndè-Tı-Yat’a) by Katłıà

Oil on Water by Helon Habila (interview)

A Diary in the Age of Water by Nina Munteanu (interview)

The Water Knife by Paolo Bacigalupi (essay)

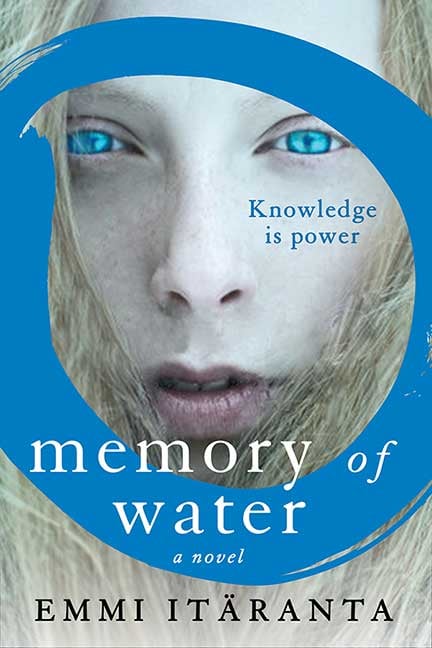

Memory of Water by Emmi Itäranta (interview)

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin

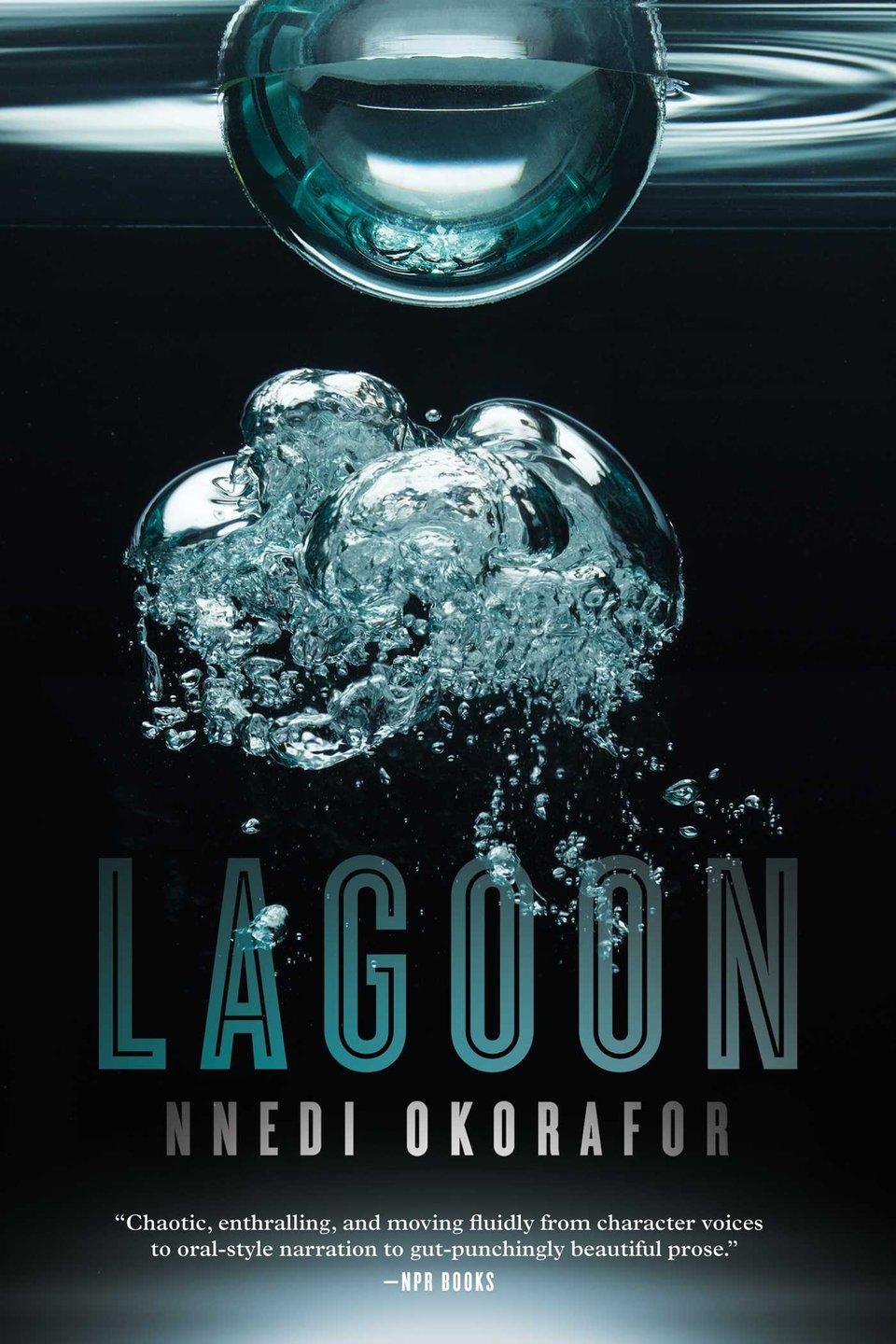

Lagoon by Nnedi Okorafor

Bangkok Wakes to Rain by Pitchaya Sudbanthad (interview)

As you can imagine, fiction about water addresses a range of ideas: scarcity, floods, oceans rising, food security, potable and nonpotable water, ecosystem health, ice, glaciers melting, beauty, healing, essentiality, hydration, fun, and so much more.

There’s many more novels and films to share; the list is huge. I also recommend Naniki by Oonya Kempadoo (interview) and other water fiction posted at Dragonfly.

Film of the month

This month’s recommendation is a documentary by Elliot Page: There’s Something in the Water. The story is set in my home in Nova Scotia. I was moved by collective groups of Indigenous and Black women who believe that it’s their sacred duty to protect the land, water, and air for their people and future offspring. They travel to the site of a dump near south Shelburne–settled decades ago by people of color coming up through the underground railroad–which reveals a toxic waste effluent dump into the tidal lagoon of A’Se’k (Boat Harbour), traditional home of the Mi’kmaq. Mi’kmaw grandmothers try to protect the Shubenacadie River from Alton Gas, which would hollow out salt caverns and dump the refuge into the water. I wrote about the film here.

A poem I wrote

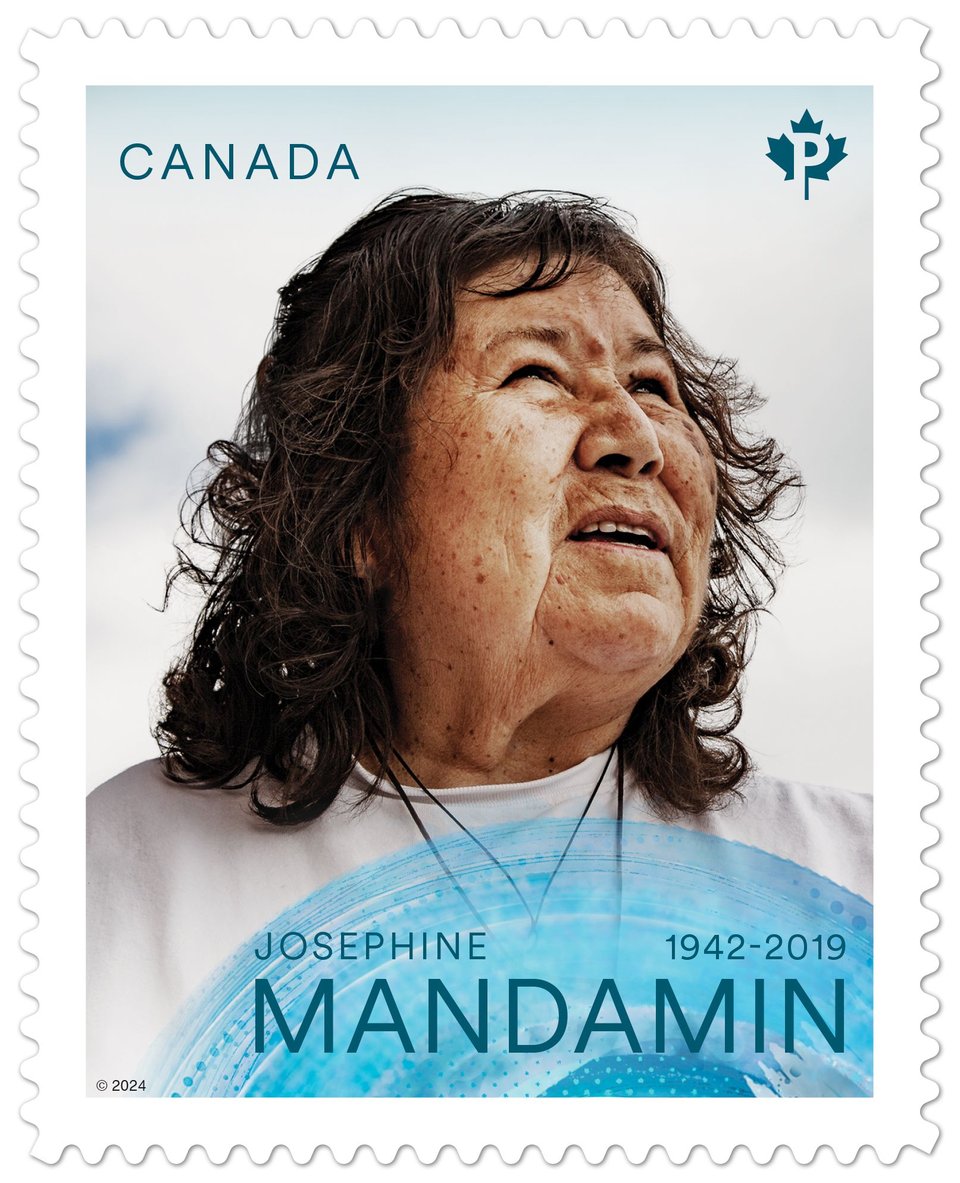

I wrote a poem in 2010, which was published at Word For/Word. It's about Josephine Mandamin (Anishinaabekwe), the "Water Walker". Josephine died in February 2019.

Josephine Anishinaabe tradition is for women to fetch the water. And there she goes. Her copper pail filled with the sun Swaying for thousands of miles She smiles, offers tobacco and chants To the waters of each great lake Her walk slow and deliberate. From Katarokwi to the St. Lawrence Where beluga whales die of cancer To the once great Erie And male frogs who grow ovum To the Love Canal— A hooker killed that. Invasive species giggle in the soup And estrogen floats with shit. PCBs banned decades ago haunt bottom layers of sediment. The water levels down four feet Coastal wetlands disappear. Flags rise off her shoulders She smiles, prays, nods People laugh at her, think She’s crazy! I think She’s the sane one.

World ecofiction spotlight

Between work, play, and gardening, I am taking more time for me and have relaxed my commitment for providing a spotlight every month. I have a couple features coming up in the next few months, but this month, I rebooted my 2014 interview with Emmi Itäranta about her novel Memory of Water.

The novel takes place in the future after climate change has ravished economies and ecologies, and made fresh water scarce. When reading, you just want to drink a glass of cold water and revel in it as if it is the last great thing you will ingest. One could never take water for granted again after reading this novel. The main character, Noria, is a young woman learning the traditional, sacred tea master art from her father. Yet, water is rationed and scarce in her future world. Her family has a secret spring of water, and, as tea masters, she and her father act as the water’s guards, even though what they are doing is a crime according to their future world’s government, a crime strongly disciplined by the military.

Other news at Dragonfly

This month’s indie corner is a chat with BrightFlame about their newest novel The Working.

Recently added novels: Theory of Bastards by Audrey Shulman, Private Rites by Julia Armfield, The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey, and The Breathing Hole by Colleen Murphy.

Resources

In case you’ve missed these exciting resources, including newest books at Dragonfly.eco, check ‘em out!

LinkTree: Find out more about me.

Dragonfly Publishing: My micro-press.

Rewilding Our Stories: A Discord community where you can find resources, reading, and writing fun in fiction that relates strongly to nature and environment.

I finally created a new playlist of “Nature, climate, and environmental songs”. Click here for part 1 (very long!) and here for the new part 2.

Book recommendations: a growing list of recs.

Eco/climate genres: They’re all over the place, and here’s an expanding compendium.

Inspiring and informative author quotes from Dragonfly’s interviews.

List of ecologically focused games.

List of eco/climate films and documentaries.

Eco-fiction links and resources.

Book database: Database of over 1,100 book posts at Dragonfly.eco.

Turning the Tide: The Youngest Generation: Fiction for children, teens, and young adults.

Indie Corner: The occasional highlight of authors who publish independently.

Artists & Climate Change. This site is no longer being updated but still has a wealth of info. I was a core writer for their team, and I’m both honored and grateful. Look for my “Wild Authors” series there.

You just read issue #56 of Dragonfly.eco News. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.