On platonic ideals and pauses

Thoughts from the scarier half of the recording studio

Recording studios have two halves and they’re both terrifying.

My typical domain is the half that the piano and all the microphones live in, intimidating in its emptiness, which I am sealed into via two separate glass doors like a zoo animal with performance anxiety. (I have written and written and written about that part of the process, so if you’re new here, hello, welcome, have fun!)

Behold: the den of terrors.

Behold: the den of terrors.

The second half is the sound engineer’s domain, intimidating in its busy-ness: the dark scary room with all the monitors, speakers, control panels, and blinking electronics with knobs and buttons whose functions I will never know. It feels like the emo teenage lovechild of a Best Buy and a Radio Shack. When I’m in there, clutching my adorably quaint sheet music with its pencil markings amid so much naked technology humming and blinking smugly away, I feel like a frightened time traveler who got off at the wrong stop.

Two weeks ago I spent some time solely in this second room to go over edits to the track I recorded last year of Florence Price’s Fantasie Nègre No. 1, the piece that was the focus of this radio story. There’s something incongruous about this process being so mundane and yet so absurd. On the one hand, I’m just sitting at a desk with a colleague clicking away at a computer. On the other hand, I’m sitting next to someone who has recorded literally the most famous classical musicians in the world, people I idolize, and he’s isolating all my mistakes and playing them at a high volume over a state-of-the-art surround sound system while I try not to have an existential crisis.

I think everyone who plays music has some kind of platonic ideal of what a piece should sound like in their head, and there is often a disconnect between that ideal and what you actually end up producing. Sometimes you know exactly what the thing you’re aiming for sounds like but you’re not physically able to make that happen. Sometimes you have no idea what it’s actually supposed to sound like but all you know is that whatever you’re doing isn’t right. Sometimes you’re convinced you’re doing it exactly the way it should be—you’ve cracked it, you mad beautiful genius!—and then listening back to a recording or getting feedback from a trusted listener, you find out that, lol, you were so wrong.

I always walk into the studio thinking that, with the magic of technology, crafting my takes into my platonic ideal is a reasonable expectation. I am then reminded that I live, sadly, in reality. (“Living in reality” continues to be a lifelong perpetual disappointment for me.)

The editing process involves making a series of decisions about what my actual goal is: do I want an unimpeachable collage of airbrushed perfection—a chamber music coach once mentioned that a famous string quartet’s recordings are spliced note by note—or do I want something resembling the unbroken and imperfect energy of a single live performance?

Sometimes when I offhandedly mention aspects of the recording process to laypeople, they’re shocked that there is any editing involved; I guess people assume performers just walk in, lay down one perfect performance, and…that’s it. Maybe some musicians are able to do this—if you are one of them, please let me know, so that I can personally resent and envy you forever.

When I recorded the Fantasie Nègre No. 1, I did three full takes all the way though, and then did a few individual passages—bits that we knew had been dicey the first couple of times, or denser passages where there was a statistically higher chance of some errant notes—so that there would be enough clean material covering the whole piece. Computers may be powerful, but autotuning single notes in a thicket of chords isn’t an option, and re-recording bits at a later date is out of the question as the variance of tuning and sound and microphone placement can make it impossible to blend a new take into the old one.

I share all this because most of the professional recording process was completely new to me back when I first recorded the Clara Schumann sonata in 2019, and for all the reading and research I do, I have never once been able to find how many takes other pianists make to record pieces, and how much editing is required. I don’t know what’s normal and no one will tell me. So here I am, being transparent about my stats for this piece, in case anyone out there was wondering.

In moments of insecurity in the recording studio, when I get self-conscious about the number of takes I'm doing, I have tremulously asked the engineer, am I normal? and he has assured me I am, but I am painfully aware of the fact that he is exceedingly tactful and extremely good at protecting the performer (me) from themselves. He’s deliberately non-judgmental about messy or bad takes, suggests breaks when he senses a spiral of discouragement on the horizon, and doesn’t ever ever ever compare me to anyone else. While it's some of the greatest professional kindness I’ve ever experienced in music making, it also feels vaguely sociopathic: is he protecting me just to get fewer, cleaner takes out of me, which makes his editing job much easier?

He probably tells me I’m normal because he knows there is actually no answer that will not wreck me. If I knew I was messier and required more takes and coddling than the average musician, I would lose all my confidence and completely break down on the spot; if I knew I was more accurate and consistent than most people, the pressure of keeping that up would create its own climate of self-doubt and cause me to completely break down on the spot.

Look, one becomes very fragile in the recording studio. Don’t judge until it’s happened to you.

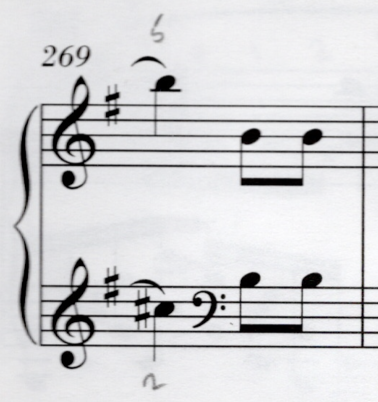

Anyway. There’s something exquisitely agonizing about hearing any imperfection or error in your own playing in front of a seasoned professional, which feels like some kind of a referendum on your abilities and life choices. At one point in the take we were primarily working from, there was a split note (the aural equivalent of a SPLAT!) in the most comically easy of measures:

In case you don’t read music: there is nothing difficult about what’s going on here. Both hands are playing identical Bs at the same time, that’s it. I could grab any old schmuck off the street and teach them to hit two Bs together in a matter of seconds. And after a lifetime of training and practice, I couldn’t do it?

“Can we grab those notes from another take?” I asked, cool and professional. The engineer tap-tap-tapped, cued up the exact spot in another take, and played it over the sound system.

SPLAT! echoed through the room.

I couldn’t believe it. I’d biffed the notes in this other take, too. What were the odds? Could I even play the piano at all?

This is why you do three takes. The spot in the third and last take was fine, so we grabbed that and spliced it in, thus allowing me to continue to dupe you all with the illusion that I am capable of hitting two notes on the piano.

There were other, far more nerve-wracking edits. There was one passage where…you know what, it’s easier if I just make a little diagram.

I am not showing you the actual notes because 1) this is easier and 2) I don’t want any of you knowing where this actually was.

I am not showing you the actual notes because 1) this is easier and 2) I don’t want any of you knowing where this actually was.

Usually edits aren’t this tight, because there’s more clean material to work with—ideally you poke around until you find one take where the entire passage is clean, and drop it in. For some reason there just wasn’t a clean take of the full passage.

Me in the studio when there are no clean takes.

Me in the studio when there are no clean takes.

The only option would be to pluck the tiny bit with no mistakes from Take 2 and surgically insert it into Take 1 and hope it worked.

To make things even dicier, the passage in question was in the middle of a dramatic tempo acceleration, so the chances of the acceleration matching up exactly was infinitesimal. The engineer made his little slices and yoinked the clean millisecond up like a helicopter rescuing someone from the ocean while I prayed fervently to whoever the saint of musical miracles is. “The tempo might not match up,” he warned while he dropped it in and massaged the joins. He backed up and hit play. I covered my face with my hands and listened in agony.

It matched perfectly. I’d somehow accelerated exactly the same at the exact same volume in both takes and you couldn’t tell there was a splice at all. I felt like we were champion sharpshooters pulling off the impossible shot, and no one would ever know. My shame at having messed up the passage in the first place was eclipsed by triumph: we were saved by my consistency, baby!!!

There were other moments where I realized I had a vision for something and had to defend it. We listened to a part of the track and the engineer stopped. “Did you hear that pause?”

I had no idea what he was talking about. “What pause?”

He scrubbed back and played it for me again. He stopped right when the alleged pause happened. “There it is.”

It wasn’t a pause, per se. It was a moment where my musical instinct was to take a little breath, like a singer, before the warm resolution of a phrase. It felt, to me, like a little airy lift before sinking into a feather pillow. I couldn’t explain why it made sense to do it that way: it just did, and doing it any other way felt unnatural to me. I stared at the spot in the score as if it had the answers. (It didn’t.)

For years teachers had told me I played too squarely, that I was too exacting with rhythm and not free enough with time, that I didn’t take enough breaths, and now here I was, having taken their advice, and doubting having done so. I didn’t know whether or not to defend the breath.

“I can take the pause out, it’s easy,” the engineer said to my silence, and I found myself confused not by the option but by the labeling of the breath, the lift, as a pause.

“Why don’t we see how it sounds if you take it out,” I said gamely. Tap-tap-tap, he went, and hit play. The end of the phrase came perfectly in time; somehow just by eye, he’d clipped it into exacting metronomic accuracy, an edit which was virtuosic in itself.

I didn’t hate it, it didn’t sound bad, but it also didn’t feel quite right to me, and I realized that this all came down to that thing we call art.

Much has been made (by me) of my efforts to make as accurate a version as I possibly can of this piece. Part of my goal was to get as close to the objectively correct notes that Florence Price intended as I possibly could. But accuracy is only the start; I’ve also tasked myself with bringing the music to life, and that involves all the decisions in between the notes.

I’ve previously quoted this passage from Jeremy Denk’s memoir, Every Good Boy Does Fine, in this newsletter, and by golly I’m going to do it again, because it’s relevant, dammit:

Rhythms in classical music appear to be notated precisely. But there is an important distinction between rhythms written on the page and the rhythms that you actually play. No matter what your piano teacher has to tell you when you’re little, these are not the same. A computer program can play back for you what’s mathematically written—it sounds horrible. The rhythms on the page of music, interpreted literally, are lifeless, or worse than lifeless, like a zombie. If you play metronomically ‘right,’ it is musically wrong.

[…] The performed rhythm is like a dance around the written rhythm, or a shading around it. The gap between written and performed is not a failing; it is the classical musician’s only hope of success.

Whether or not to leave in that breath—I refuse to call it a “pause”—was a small but existential grappling; removing it would be technically correct, and likely no one would listen and go, “Hmm, I wish there was a tiny breath there!” I just liked taking a little breath there, but was “I like it” enough to justify leaving it in and risking listeners thinking that I can’t keep time? I wished in that moment that I could use the “Phone a friend” lifeline on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire and consult any of my old piano teachers.

“Hi, this is Sharon, your old student! Whatever you’re doing right now, can you drop it and listen to this recording I’ve made of Florence Price’s Fantasie Nègre and just let me know what you think of this little moment where I take a breath before the resolution of the theme? And then can you listen to the whole thing again but in a version where we’ve taken the little breath out? And then tell me if you think the little breath distorts the overall architecture of the passage, or if being too metronomic undermines the freedom of the moment?”

If only.

I took my fate into my own hands. I stood up to defend everything I held dear about that breath: my own musical instincts, my intention to be less square and more free, my own internal tension between straight-laced order and limitless exploration.

“Let’s leave it in,” I said.

The engineer shrugged. “Okay.” He hit Ctrl-Z.

No one is going to notice the tiny breath. But I know it’s there, dammit.

The track will be released sometime later this year. Here’s an itty-bitty preview.

Quick housekeeping

Some subscribers reported having some trouble with setting up custom amounts for paid subscriptions to this newsletter; I think I have fixed it now. If you follow this link, you should now be able to set whatever you want as a monthly subscription. Feel free to respond to this email if that's not the case and I can poke around on the back end to get things straightened out.

If you want to toss something into the recording fund but don't want to commit to a monthly subscription, I also have a dusty old Ko-fi page.

Thanks for reading!

Add a comment: