On Horses and Schubert

Things that have broken my brain, and the revelations beyond

Recently in my riding lessons I went from doing one-off jumps to doing long (to me) sequences of 6-8 jumps, which means I have somehow achieved my childhood dream of being a concert pianist and equestrian jumper at the same time, which I think is right up there with “astronaut princess” and “firefighter president” in terms of implausible childhood dreams.

We did it, Joe.

If you have too much going on in your brain like a conscious person in the year 2026, and want to have too much going on in your brain like a jock whose head is just filled with circus music, I highly recommend jumping. It’s an activity that will flood your little head with so much that you can’t possibly think, guaranteed.

Because as it turns out, stringing together over half a dozen consecutive jumps, with the turns navigated correctly in order to set them up, creates a mental load so staggering I half expect the computer of my brain to freeze up completely.

Here's your brain on jumps: you’re checking that your weight is in your heels, that your knees aren’t constraining the horse’s shoulders, that your calves are wrapped improbably against the barrel of the horse’s sides and pressing in for dear life, that your pelvis is angled back, that the right part of your butt is glued to the saddle, that your belly button is pulling you upwards, that your hips are correctly absorbing each movement, that your lower back is pulling firm against your arms like an accordion being pushed in, that your upper back is stretching up, that your hands are both holding low and steady and also feeling the bit in the horse’s mouth and adjusting the position of her head to align with the jump, that your shoulders are firm but not locked, that your eyes are looking ahead and never down (down is death), that the crop in there somehow tucked between your fourth finger and pinky (don’t drop it), that when one individual part shifts you’re adjusting all the other parts correspondingly, that you’re doing all this while rocketing up and down and around at what feels like a million miles an hour on top of a monolith of skittish muscle, that on top of all of that you have to count and feel the beat before launch the way a conductor feels the ictus before the downbeat…

It is all so impossible that I can’t believe anyone does this without their heads exploding. It’s like playing a Bach fugue on a seesaw on the deck of a ship that’s also on fire.

I’m at the point where my trainer is giving me advice that sounds eerily familiar—telling me to quiet excessive motions, release the tension in my shoulders, drop my hands, count the beats and know where the rhythm is going, think ahead—oh, where have I heard all of this before?

All my tendencies and mistakes, it seems, have merely replicated from one discipline to another. I have the same habits of tensing up, of collapsing my back, of gripping tighter when I need to let go and loosening when I need to hold firm. Multiple times I’ve nailed the landing of a jump and veered triumphantly off in the wrong direction, and then realized too late that I had completely forgotten I had four more jumps after this one, that there was an order to them, that the world was a little bigger than I thought and that I’ve now screwed everything up. It’s exactly like when I would stick the landing on a technically demanding passage of music in a lesson, then lose my head and bungle the simple I-V cadence at the end of the phrase because I completely forgot what key I was in. (“Are there E-flats in E-flat Major?”)

I know at some point these controls and adjustments will transfer from conscious to subconscious, that it’ll become second nature. For now, though, I enjoy this terrifying mental state immensely. When you’ve done enough classical training, something happens to rewire your brain and turn you into a complete freak. I am aware that most normal people prefer not to first be overwhelmed and then be yelled at while in said state of overwhelm, but I love it—it is, perversely, one of my comfort zones.

Performing a mentally demanding physical activity with a high probability of failure while an authority figure yells instructions that you don’t think are physically possible? That’s not torture, it’s my happy place. (I said once that something has to be very wrong with you to play the piano, and I stand by it.)

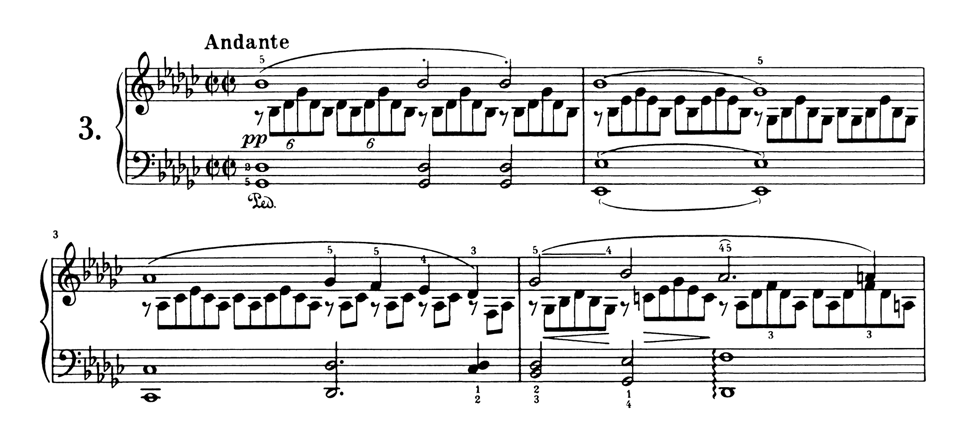

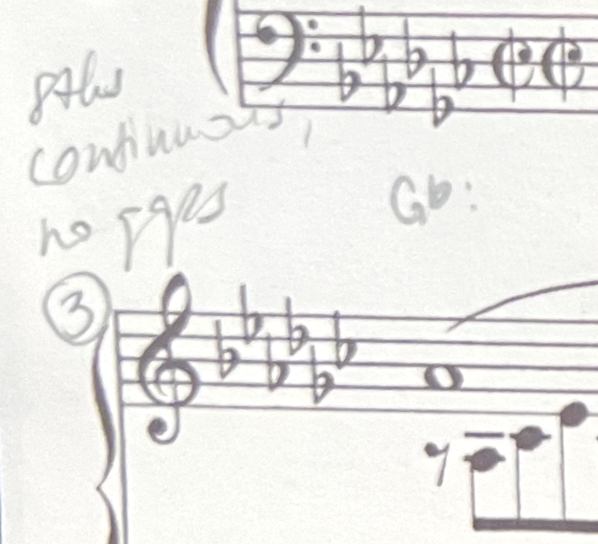

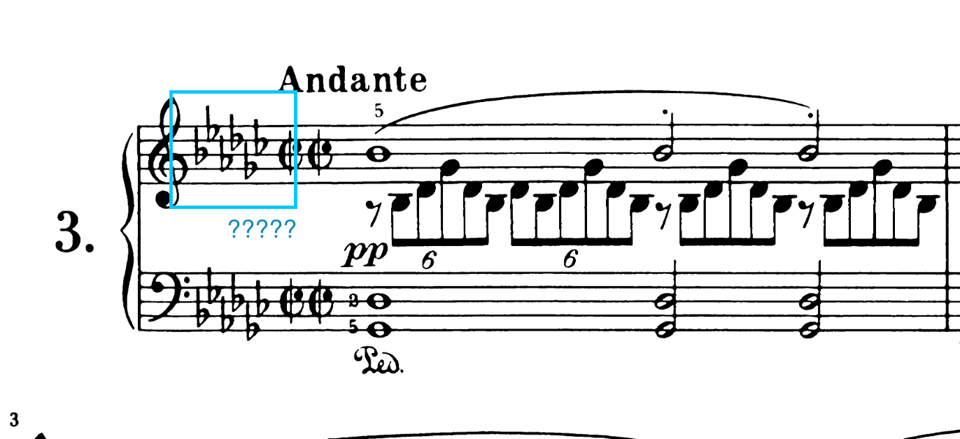

I recently pulled out Schubert’s Impromptu in G-flat Major, a piece a teacher assigned to me over a decade ago (!) as part of a campaign to break me down and build me back up, and I realized that working on this had been strikingly similar re: being yelled at while trying to do impossible things. It really speaks to the gorgeousness of this work that getting the bootcamp treatment didn’t put me off of it for life. (I am motivated by beauty in a way that might be problematic.)

Inspired by a Schubert-y moment in a Clara Schumann piece I’m working on, I started relearning the Schubert, which immediately brought me back to the Sisyphean ordeal of playing the Impromptu to my teacher’s satisfaction. I realize, looking back, that I was doomed to never have been able to meet his standards that year—if I could, I wouldn’t need his instruction in the first place—but I didn’t know that at the time, and so I strove like someone who didn’t know that the rock always rolls back downhill.

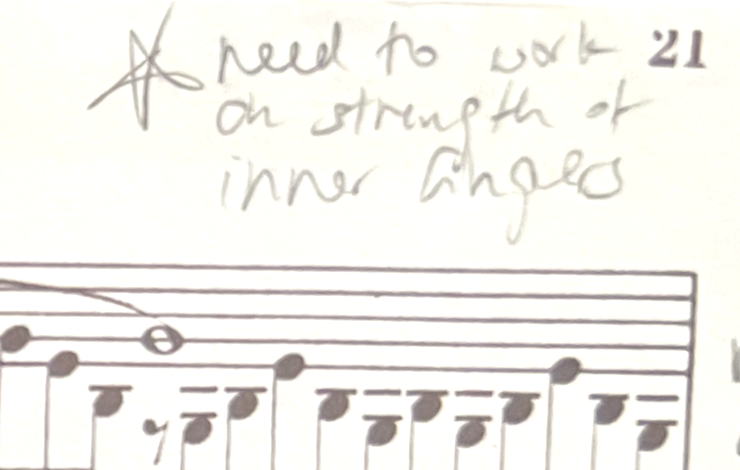

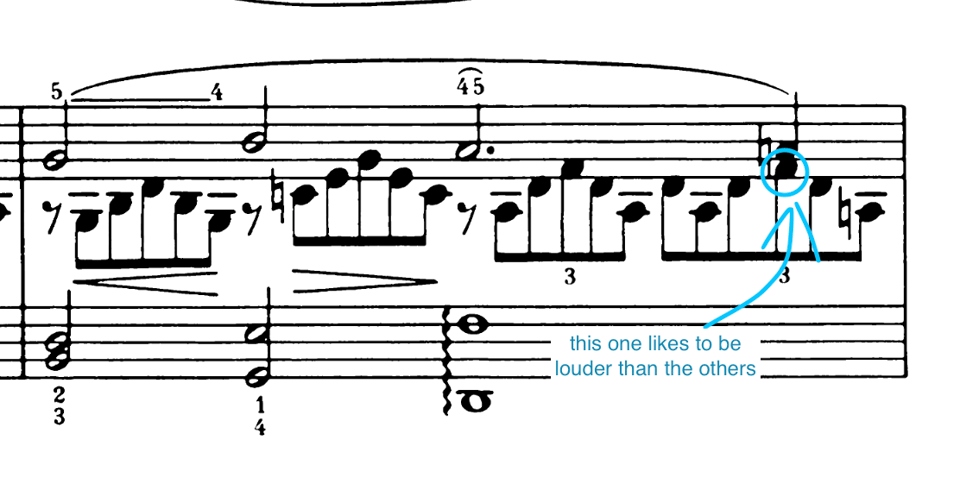

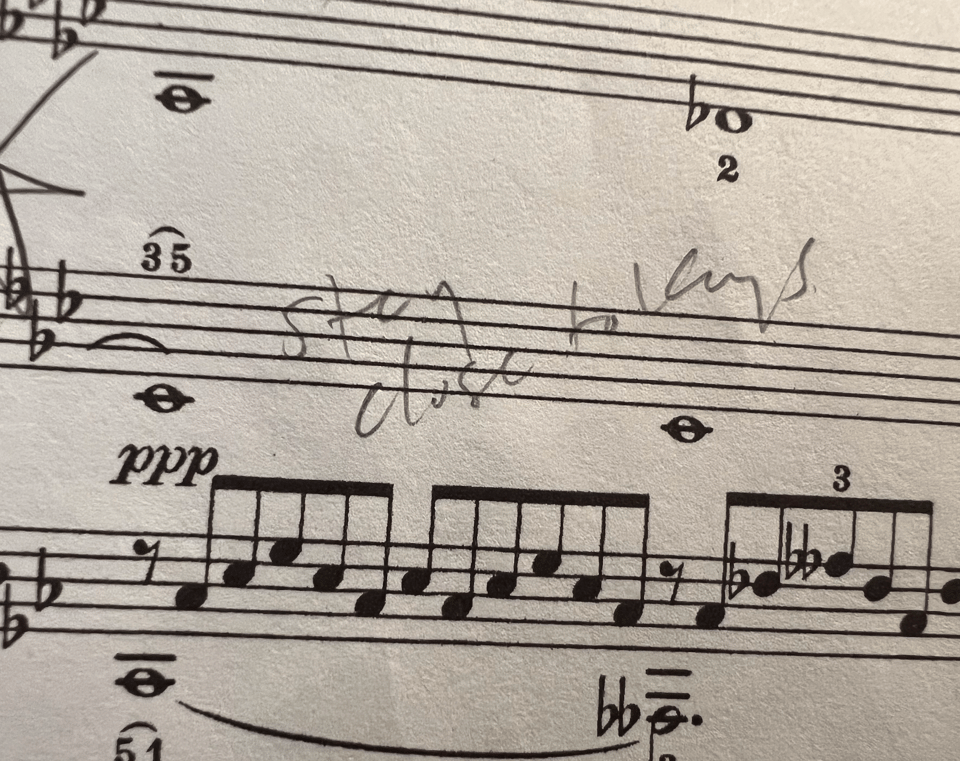

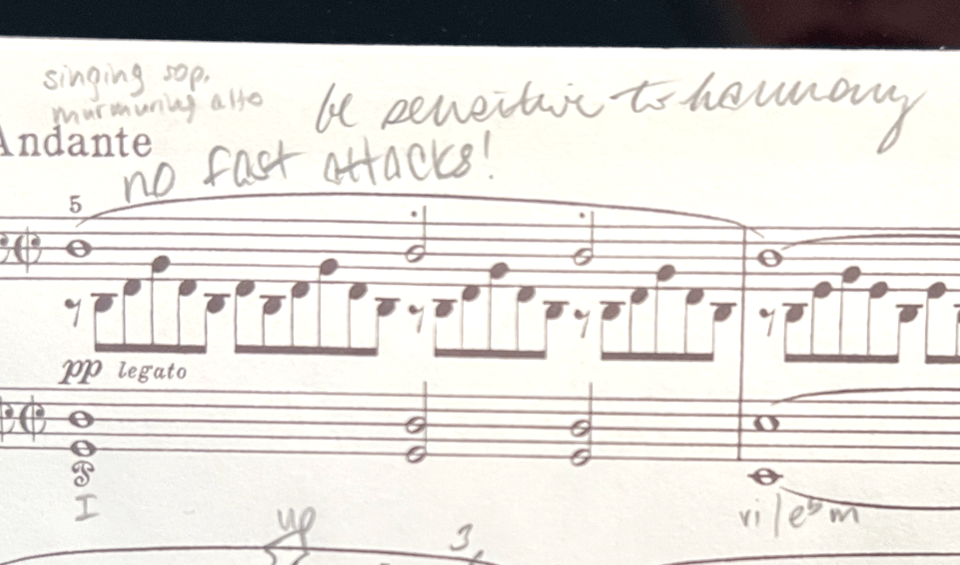

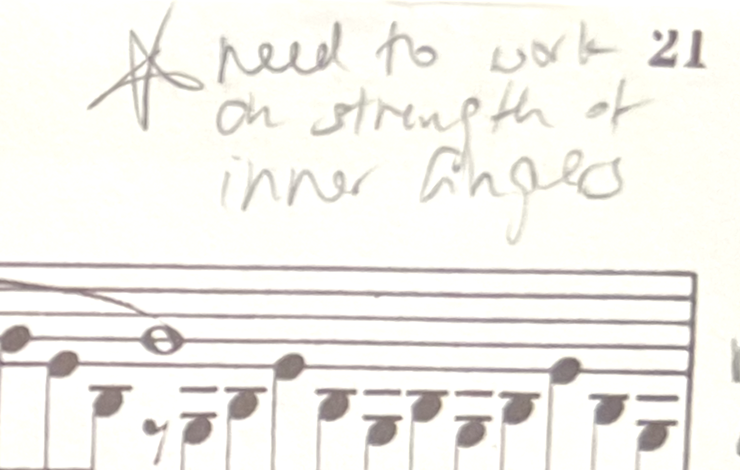

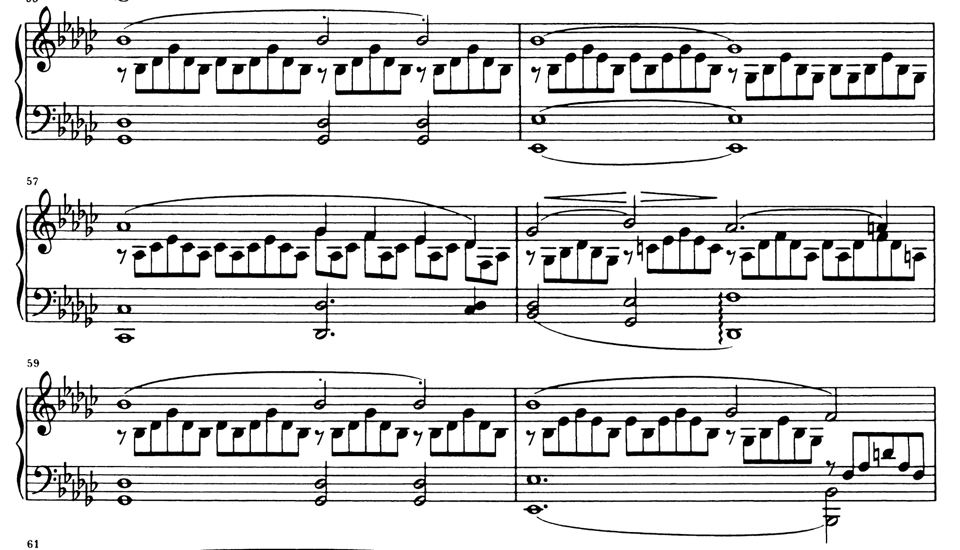

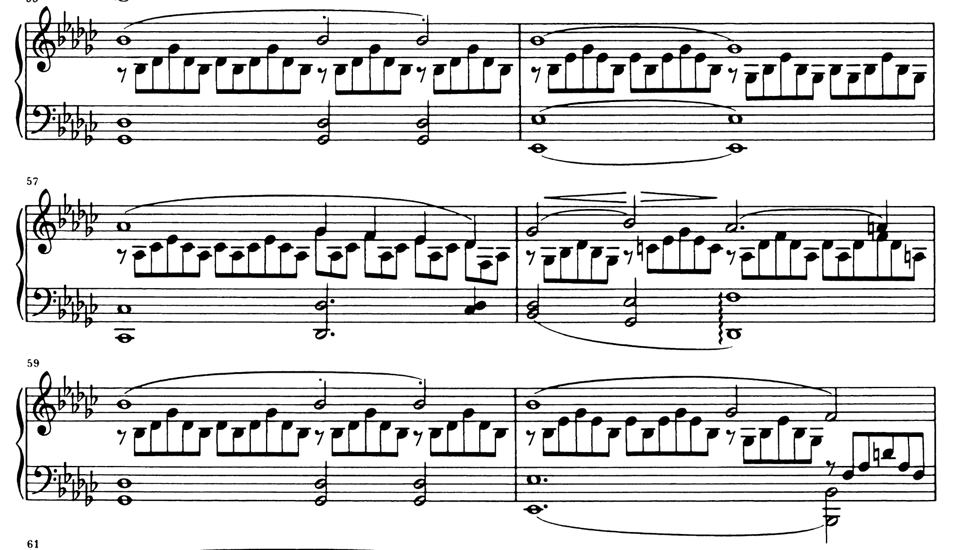

Throughout the Impromptu, the inner notes quietly ripple under the melody, and thus have to be a lot softer—any yokel could tell you that, but my teacher demanded far more than just “little notes quiet, big notes loud.” To start with, every single inner note still had to be clearly heard—it’s all too easy to drop or swallow a quiet note and not notice, but my teacher could pinpoint when a seemingly unimportant note didn’t sound with perfect clarity.

Then because the inner notes fall unevenly in the hand, making each one audible meant that some, naturally, became microscopically louder compared to their neighbors, so I had to calibrate and adjust each microsecond-long note passing under my fingers.

Then all the notes, being the same volume, had a flat sound because there was no overall shape giving the feeling of rising or falling to the figurations, so I had to incorporate shape into these little notes.

This then made them rhythmically uneven, which meant I had to spend hours grinding away, evening them out.

Then the inner notes and the outer melodic notes all came out having the same tone—there was no depth to the texture, the same way painters have to color a distant mountain range a lighter color than the foreground to communicate depth—so I had to work on playing the outer notes both with a different part of my fingerpads and with a different motion, with the inner notes originating at my fingertips, pulling inward, and the melodic notes originating from my arm, pushing outward.

(Doing all of this caused my elbows to rise upwards like a marionette, so I had to devote part of my attention to sinking the weight of my arm downwards for a deeper, more beautiful sound, which sometimes constricted the motion of my fingers, forcing me to recalibrate everything all over again.)

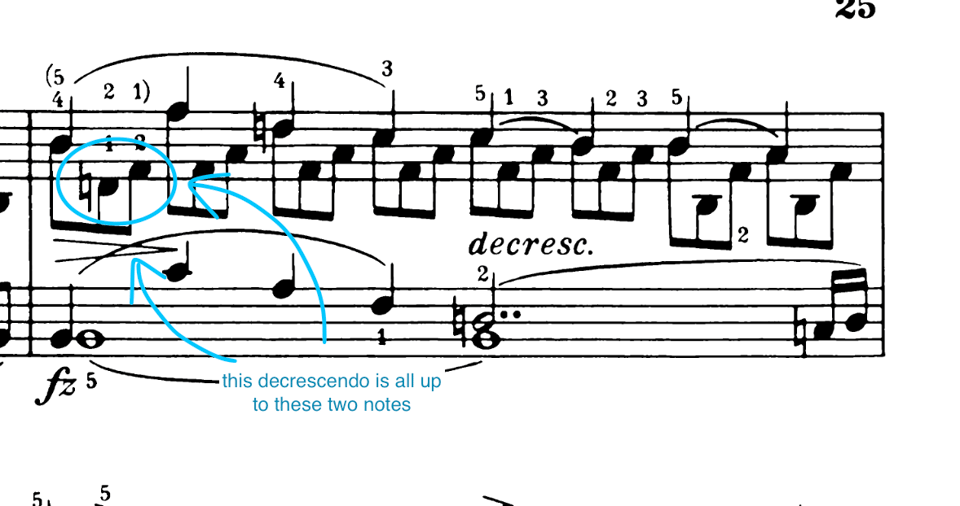

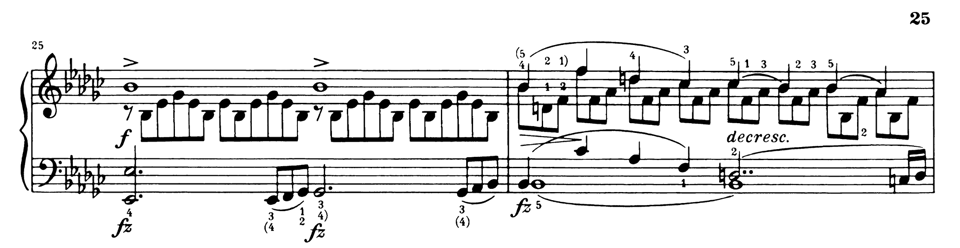

When I finally, finally, maintained some semblance of the precarious balance of volume and tone this Impromptu required, with the inner notes appropriately even, I ended up with an entirely static melody that had no forward momentum, no buildup and comedown—“square” and “vertical” were the dreaded words I heard a lot in those days. My chord changes were matter-of-fact, and there was no sensitivity or expression, which was an entirely new criticism of my playing, as up to that point my entire life I’d been praised for the natural expressivity I always got without even trying.

I shoehorned as much expression and movement as I could into the piece, shoving rubatos and surges and breaths anywhere I could fit them, the way you cram clutter into the crevices behind things right before a friend comes over…which caused my carefully worked inner notes to drop and become uneven again—which sent me back to square one.

Like I said, you have to be messed up to want to play the piano.

I know for a fact that no one enjoyed me playing the Impromptu that year. Mentally juggling all the contradictory physical requirements on top of playing by rote memory broke my brain each time, and in a way that I wouldn’t quite experience again until the aforementioned jumping. My teacher was never satisfied with the tortured renditions I eked out, no matter how many hours I poured into a piece that, let’s face it, isn’t actually that technically demanding.

Little wonder that I never got around to plumbing the emotional depth of the piece—how could I have the mental bandwidth for it? That’s like asking me to compose original poetry while navigating an eight-jump course—nice try, it’s simply not going to happen.

These last few weeks as I started relearning the Impromptu, I approached it differently from when it was first assigned to me, and I realized that there was so much to the craft beyond an overwhelmed brain and internal screaming.

I started asking questions. Why does this piece stir up so many complex un-nameable feelings? Why does it feel simultaneously like pleasure but also like pain? Why does it feel close to heartbreak, but not quite? Why the heck does it have so many flats?

The harmonies of the Impromptu shift quickly, as mercurial as daylight when clouds drift across the sun, so the major:minor::happy:sad dichotomy doesn’t work here. There are major chords that ache in ways minor chords can only dream of. The piece seems to exist in a different plane of existence.

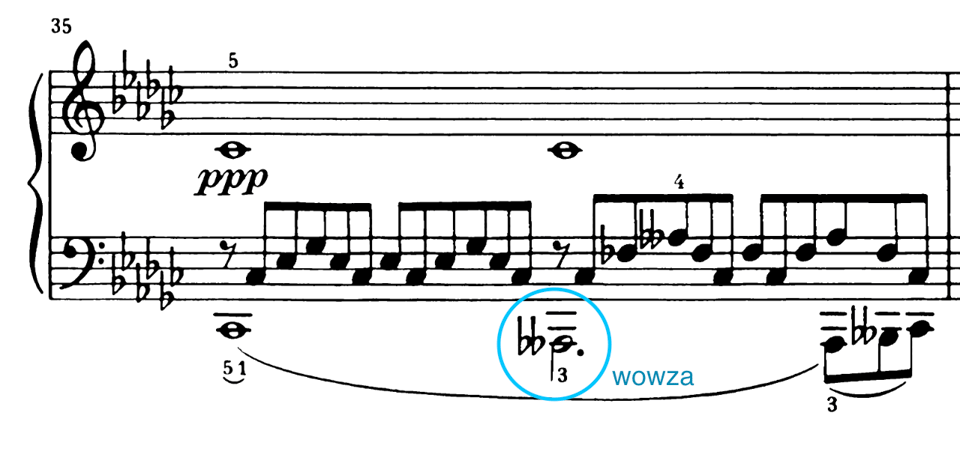

While I rememorized the bass line and harmonies in the dark B section, I realized there was a sensuousness to the chord changes that I had completely missed when I was sweating the small stuff. There are moments where a single note just slips!—oops!—downward, as casually and provocatively as letting a strap fall down your bare shoulder, a single tiny action that changes the temperature of the room.

I used to puzzle over the emotional content of the B section—it’s dark but not angsty like sturm und drang, filled with tension but not outright conflict. How do you play something that is a lot of almosts and not quites when you don’t have a clue what any of it is meant to be?

It finally occurred to me this week what this section felt like: it has the energy of letting yourself be wholly consumed by a desire you know will wreck you. It’s got the same fatalistic, falling-backwards-into-the-abyss-in-slow-motion feeling that I love about the ††† song “Bitches Brew.”

The surrounding A sections, on the other hand, have more of that classic golden “being in love” feeling, but there’s still an emotional distance to them that I couldn’t quite figure out. Exaggerating the emotional content causes these sections to sound overly sentimental, while doing the opposite gives them a coldness that doesn’t quite work. What is going on? Is it love or is it heartbreak, and why does neither seem to quite fit?

Then it hit me—the many-flatted key is a clue. This piece could have easily been in G Major instead of G-flat—one sharp instead of six flats, and indeed there are published versions of this work in G Major—but G Major has a certain brightness and immediacy that doesn’t quite gel with what’s going on in the Impromptu. Shifting the whole thing down a half step, away from the orange-juice-sunniness of G Major, washes the piece with a sepia tone, imbuing it with a sense of memory.

My understanding of the piece clicked into place. This piece isn’t speaking from a current state of being in love, or even in the immediate wake of heartbreak; there’s a distance to it that indicates that enough time has passed to color the whole affair. It’s retrospective, regretful, bittersweet.

The distance makes the memory of love a more private, vulnerable thing. When you’re in love you want to shout it from the rooftops; when your heart is broken you want to scream it into the void; when you’re reflecting on the memory of love without a happy ending you want to whisper it only to yourself when no one else is listening.

The moments of innocent, brimming joy in the A sections are a memory of innocence, like a faded polaroid from childhood. The moments of being devoured in black fire in the B sections are a memory of such, tempered by intervening years. Whatever heartbreak has occurred—and occurred it definitely has—it’s happened off-screen. Only the narrator knows how the story ended.

Schubert, who hurt you? Does it matter? The heart broke, it mended, the story was told, and now we have music that helps all of us process those private bittersweet feelings. I have no idea how the hell I’m going to make all these complex, multi-layered thoughts come through in my playing, but at least I can count on one thing: I’m not going to be held back by those pesky inner notes. I put in the damn work.

Do such breakthroughs await for me on horseback? We will have to see.

Listening on Repeat

When Florence + the Machine’s album Everybody Scream came out at the end of last year, I listened a few times and went, “Hmm, this album is okay, it’s probably not one of my favorites.”

Then I kept being drawn back to it, needing to listen to it again, not knowing why I was being pulled in repeatedly like the tide. Something crossed over for me the past couple of weeks and I realized that this had, somehow, become an album I can’t live without.

Florence Welch somehow captures the tension of being both a public and private person, of being eaten up by grief and pain while still needing to be seen and adored. She is defiant—about her womanhood in a world made for men, about her private wants—in a way that makes something inside me vibrate with sympathetic resonance.

It’s gotten to the point where “You Can Have It All” has become a quasi-religious experience for me. The slow burn of the opening, building so deliberately it’s excruciating, is just so good—the first payoff doesn’t come until 1 minute and 35 seconds into a 4 minute track, and when it does, whew. Welch wails “you can have it all” with so much irony and bitterness that each time, I feel something inside me release.

Between Florence + the Machine and Schubert giving us art from their most private pain, who needs therapy? (All of us. We all need therapy. The music doesn’t hurt, though.)

Hugoposting

The Hugoposting has, against all odds, continued, and I am getting a lot out of reading Les Misérables in 2026. Like, a lot. Here are the posts I’ve written since the last newsletter.

Book 2

- Chapter 3, “Now We’re Cooking”

- Chapter 4, “Let’s Just Casually Talk About Cheese Dairies”

- Chapter 5, “How to Answer Awkward Questions”

- Chapter 6, “The Gritty Origin Story”

- Chapter 7, “What Prison Does to a MF”

- Chapter 8, “About the Sea”

- Chapter 9, “French Holidays Will Get You”

- Chapter 10, “Insomnia Besties”

- Chapter 11, “Hear Me Out: Jean Valjean is a Cat”

- Chapter 12, “We Have Attained Peak Bishop”

- Chapter 13, “Tough Look For Our Guy Valjean”

Book 3

- Chapter 1, “Everything Happens So Much”

- Chapter 2, “I’m Getting Bad Vibes”

- Chapter 3, “Je téléphone à la police“

- Chapter 4, “He’s a Leg Guy”

- Chapter 5, “[Frenchness Intensifies]”

- Chapter 6, “Queen of the Dinnerwhores”

- Chapter 7, “Throw the Whole Man Away”

- Chapter 8, “Fantine and I Are Right (About Horses)”

- Chapter 9, “Goodbye, Douchebags”

Book 4

Book 5

- Chapter 1, “An Industry Ripe for Disruption”

- Chapter 2, “Big Bishop Energy”

- Chapter 3, “The Platonic Ideal of a Rich Guy”

- Chapter 4, “I Am Distraught”

- Chapter 5, “Enter Javert”

- Chapter 6, “The Cart Scene”

- Chapter 7, “It’s a Happy Ending, So Why is There More Book”

- Chapter 8, “Doing Nothing is Free”

- Chapter 9, “Hell is Other People (This Person Specifically)”

- Chapter 10, “Fantine is Not a Girlboss”

- Chapter 11, “Do You Get the Fantine/Valjean Parallels Yet”

-

How would you think about the piece if it were in F# major? (The late key change, I think, would actually be more straightforward.)

Add a comment: