On fire

Disasters, salad, and the time I was rude to a piano salesman

Three weeks ago, my husband and I took a little road trip. We drove up the Pacific Coast Highway, past all the iconic shorefronts of Malibu, into the beginnings of Ventura County. We marveled at how beautiful the Southern California coast is, how seeing it even in the dead of winter just makes you happy to be alive.

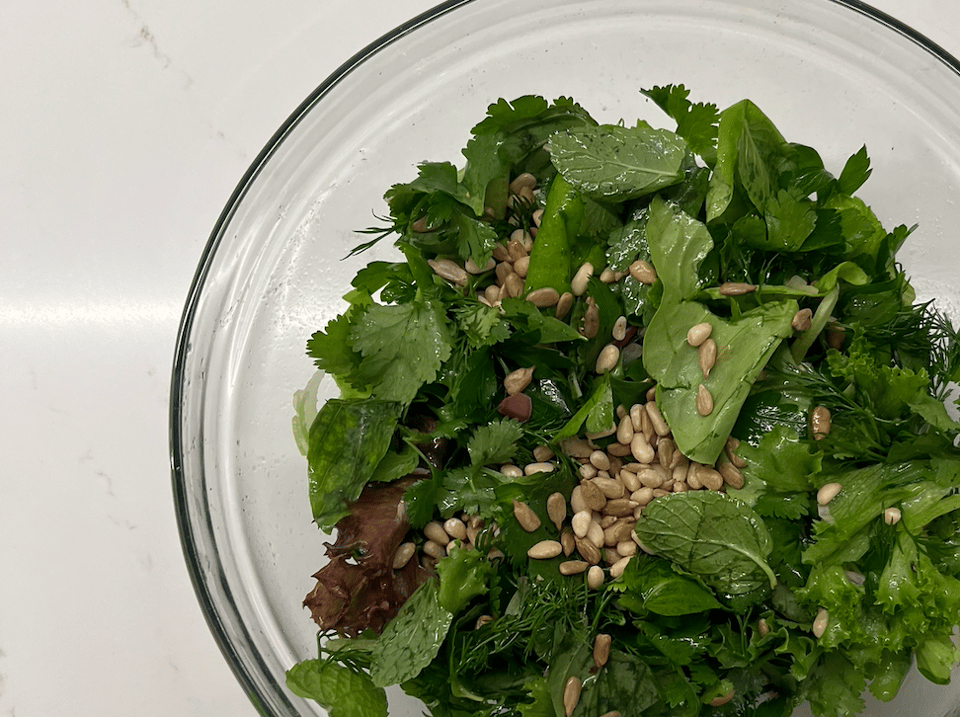

We went to dinner at Rory’s Place in Ojai and, as we usually do at restaurants, we huddled over the menu and planned out what to order with the strategic determination of decorated military generals. My mom taught me to have vegetables with every meal, so we obligingly tacked the herb salad on to our order. A lot of restaurants don’t do much with their salads—it’s often a half-hearted “here you go, you health-minded freak” more than an opportunity for a chef to do something special—so I didn’t have high expectations when I lifted that first forkful to my mouth.

What I ate blew my mind more than any salad should. Instead of the usual salad base—your lettuce, your kale, your mesclun, your frisée, your bagged spring mix—the herb salad used herbs for its greens. Fresh, soft, piquant herbs: cilantro, basil, parsley, shiso. Every bite was a joy, the culinary equivalent of those concerts that are so good you just go into a sort of blackout of delight.

I decided right there that I would make herb salads a thing at home. I would practice, I would experiment, I would try different combinations and ratios and tweak the dressing until I could nail it every time (I am always musicianing) and experience that sensory joy on demand.

We drove back down the Pacific Coast Highway, chattering happily about what a great time we had, agreeing that salad had been amazing, not knowing that we were thoughtlessly enjoying some of the scenes before us for the last time.

On the third day of the fire, we needed groceries. I put a respirator on, went to the grocery store, and wondered how it was possible to decide what to make for dinner. Everything was happening so much. Because I had no other direction, I remembered how much I’d wanted to make an herb salad. So I bought herbs. I took them home. I made a salad.

Making herb salad is tedious. I stood at the kitchen counter with a heap of herbs on the cutting board, painstakingly plucking the leaves off each stalk and watching the leaves slowly pile up in the salad bowl. It was like drilling a four-bar passage over. and over. and over. again, very slowly, corseted by the metronome. (Once again, always musicianing.) For some people this is hell, but that time spent gently preparing herbs was the first time in three days that I had a real moment of peace.

For once, I wasn’t frantically toggling between the Watch Duty fire map and the official county evacuation maps, refreshing local government web pages every minute to see the latest update, texting the family and friends and acquaintances and everyone, it seems, who ever got my phone number, who were all piling into iMessages frantic to know if I was safe, who at a much safer distance than me were more scared than I was and who wanted me to assure them I was okay and answer all their questions about what was going on and what the situation looked like and how far away was the fire from me and how bad was the smoke and did I have my bags packed and did I have someplace to go and was this museum okay and was that one road open and have I seen this update from six hours ago and have I seen this video in the news and was I very close to that thing that burned down and they were so scared for me and had I heard and and and and

You don’t know what luxury is until your city is on fire. Luxury is a moment of quiet when the only thing on your mind is an enormous pile of green herbs. Luxury is enjoying that moment of quiet in your own house which is still standing. Luxury is breathing blessedly clean air through your respirator at the grocery store and filtered by the air filters in your house which you bought several wildfires ago. Luxury is a mouthful of fresh herbs from a bowl on your own table while people you know are huddled in hotel rooms and evacuation centers watching their homes burn on TV. Luxury is the guilt of knowing you are so lucky when misfortune is an avalanche.

I made dinner and cooked with all the things that, 48 hours ago, I had been willing to never see again. The Le Creuset we got as a wedding gift, the Peugeot salt and pepper grinders we treated ourselves to last year, the Crate and Barrel bowls that had survived four moves: I had been ready to lose them all, I had been ready to make that bargain for our lives, and yet here I was, making dinner like nothing in the world had changed.

When the fires threatened, on Tuesday night, to promote themselves from a local tragedy to an internationally televised disaster, I had the weird feeling of having studied for this. It’s not just that there have been so many increasingly frequent wildfires in California, or that we’ve consulted the emergency preparedness checklists. It was that I’ve studied disasters, what happens in disasters, what people feel in disasters, with an academic-minded remove.

I read obsessively about disasters as a kid and took a course on disasters in history in college (it was one of my favorite non-required courses). Rebecca Solnit’s A Paradise Built in Hell, with its profound insights about human nature and the bonds of community in apocalyptic situations, made such a deep impression on me that I gave it out as a favor at our wedding. And last year I read John Vaillant’s Fire Weather, which, besides being absolutely terrifying, gave me a better understanding of what catastrophic wildfires and firefighting look like in our petrol-fueled era of climate change.

And yet nothing can quite prepare you for what it actually feels like to see the flames with your naked eye from the street you live on. Did you know that wildfire, from a not-far-enough distance, blobs around like the globules in a lava lamp? I don’t think I will ever be able to unsee it, the insouciant dancing so lazy it’s insulting.

A weird sense of calm settled over me like a mantle after I saw the flames. Everyday life is infinitely difficult and confusing and I can be paralyzed by situations like not knowing what to have for dinner or having to send an email, but seeing lava lamp fire on your doorstep will sort that all out immediately for you. I was hit by a clarity so intense it was like a religious experience: I must keep myself, my husband, and the cat alive. Everything else is optional.

We packed our bags. It used to be that when I saw disasters on the news, I’d wonder how I would make decisions about what to take and what to leave if it came down to it; everything in the house has memories attached to it, is beyond precious and sentimental.

Clarity has a way of driving out sentiment. I left all the gifts and the beautiful fancy things I’d saved up for. I left the shelves of journals painstakingly documenting my doings and thoughts and feelings and every single practice session and master class and lesson I’d had in the last thirteen years. I didn’t even glance at the library of sheet music accumulated over decades, filled with a lifetime of irreplaceable markings and fingerings and instructions from multiple teachers. I left the books signed by pianists I idolized, some now passed. If I lost all these things that were a record of my life, the clarity told me, I could mourn them later, but there was no point mourning now.

I was willing to walk away from all of it. And the piano—one of the evacuation packing guides names musical instruments as things you should take with you, but how on earth do you evacuate with a grand piano?

The piano is one of the great triumphs in my history of grown-up purchases. For years in the Bay Area I rented a grand piano, and even though the very nice salesman gave me a generous break on the price after hearing me play Chopin in the warehouse (sometimes, practicing hard does actually save you money, kids!), it was one of those boots theory situations where, over the period I rented that piano, I ended up paying more than what it had originally retailed for.

So when we moved down to LA, we agreed that even though we didn’t know how long we’d be here, it just made more sense to get ahead of things and buy a grand piano outright. So we hit the dealers. I trotted out Chopin etudes and tested the double escapement action on a cascade of keyboards. In the end I liked the first piano I’d tried at the first store the most (a baby grand that sounded twice as big, the way some very short people have six-foot-five personalities) so we returned to the first store, to the great cheer of the store’s owner.

“You’re back! You must have liked me!” he announced happily when he saw us walking back through the door.

“I’m just here for the piano, I don’t really care about you,” I said. It was one of those too-honest things I say sometimes when I momentarily forget that people have feelings. The owner recoiled. And thus I kicked off what has now become legend, That Time Sharon Totally Owned a Piano Dealer.

We sat down to do all the paperwork involved when one transacts in overlarge pieces of noisy high-maintenance furniture. Moving past my accidental shot across the bow, the owner began peppering us with charming-invasive questions about our financial situation, perhaps assuming that any girl clearly this lacking in social graces who can sit down and play Liszt on demand is not a real decision maker. He kept turning his head to address my then-boyfriend (now husband) who was intentionally seated off to the side, asking him what he did for work, angling for a ballpark figure on his yearly salary, making decreasingly subtle comments about how it was really my boyfriend calling the shots and buying the piano.

I can only put up with someone making a situation unnecessarily weird for so long. “I’m the one buying the piano, for me, with my money,” I said firmly, looking in the owner’s eyes and pulling out the checkbook. “How much of a discount can you give me?”

To this day my husband will crow to anyone who hears that I am a stone-cold negotiator who can lay any salesperson low (prior to this I’d broken a string of car salesmen and driven off in a brand-new sports car that I got for a stupid low price with years of free service and lifetime navigation thrown in), but honestly, what followed was so easy I feel like the legend is unearned. The piano dealer ceased all attempts to be charming and moved with the accommodating alacrity of someone who just wants the mean girl in front of him to go away. He saw me bracing for a knockout haggling session, the way a cat wiggles its hind right before it pounces, and hastily tossed me a fat discount on the spot. I asked for a better bench—adjustable with padding—and he threw it in for free (with only some muttering about how he usually charges for upgraded benches). First tuning and delivery: free. When the tuner came on the piano store’s dime after the piano had been delivered, he asked me how much I’d paid, and when I told him, he couldn’t understand how I’d gotten a brand new piano that good for so little.

Part of my fondness for my darling baby grand comes from the fact that I feel like I won it (through being a rude asshole). I don’t know if the piano likes that it ended up with someone who beats it up for hours every day, but I love that we found each other, and I really love that I got it with a discount I will probably never get again in my life. When I dust it I feel like I’m grooming a particularly well-behaved horse, and when I schedule tunings I put them on the calendar as “Piano gets a checkup.” It’s more than a piano to me; it’s family.

And yet in my lightning packing session, I didn’t think about my piano at all. It was just as well; there was nothing I could have done to save it. All around LA, countless people had been making the same decision to abandon some of their most prized possessions. That urgent clarity—none of this matters more than your life, leave it and go—was in the air for all of us that day, stronger than the smoke and the flame.

When you imagine yourself living through a Disaster, you imagine the shock, the fear, the grief. I was not prepared for the sheer amount of annoyance: I’ve been annoyed at people far away who were more scared for me than I was scared for myself (who has the luxury of feeling scared when survival is on the line?). I’ve been annoyed at people with main character syndrome who weren’t near evacuation zones who evacuated from the places that people were evacuating to. I’ve been annoyed at well-meaning people outside of LA and California sending me outdated updates (do you think I don’t already know these things, or that I missed a dozen emergency alerts?). I’ve been annoyed at online bystanders suddenly becoming experts in LA water systems and weather patterns. I’ve been annoyed at faraway people nowhere near danger wasting the limited focus of our survival-mode brains with Theories and Explanations.

The annoyance, I think, comes largely from the disconnect between what people think it was like and what it was actually like in the moment. While people far away were freaking out and telling me I must be so scared, I was under that temporary spell of beatific calm and clarity. We were packing quickly and decisively, shoveling cat food and important documents into our bags, but without a firm evacuation plan other than “drive in the opposite direction of the fire.” I had—and this sounds insane given that I am not a religious person and this was a lives-in-danger crisis—a sense of faith, based on 0% experience and 100% belief, that people would come through and we would be okay, and despite the freakiness of the situation I was already full of love and gratitude. You can blame Rebecca Solnit for that one.

In A Paradise Built in Hell, Solnit doesn’t shy away from the fact that humanity can be terrible (the chapter on New Orleans when Hurricane Katrina hit is hard to read), but her main thesis, which she proves masterfully, is that the wakes of disastrous events create the closest thing we have to utopias: temporary states where the transactional nature of society has fallen away, where members of a community bound only by physical proximity provide unconditional help and support; that the violent, selfish “everyone for themselves” mental picture we have of a disaster-torn place is a fiction. She writes:

The existing system is built on fear of each other and of scarcity, and it has created more scarcity and more to be afraid of. It is mitigated every day by altruism, mutual aid, and solidarity, by the acts of individuals and organizations who are motivated by hope and by love rather than fear. They are akin to a shadow government—another system ready to do more were they voted into power. Disaster votes them in, in a sense, because in an emergency these skills and ties work while fear and divisiveness do not.

As we packed, with no idea where we’d go, phones blaring with the heart-attack-inducing squall of evacuation orders, people emerged and plans made themselves for us. Family and friends and people I’d never met two or three degrees of separation away immediately offered up their homes all over LA and Southern California, promising beds and showers and meals in places that weren’t actively on fire. People I hadn’t talked to in years messaged me offering me help and it wasn’t weird at all. Something something the real doomsday supplies are the friends we made along the way.

In the days since the fires obliterated parts of LA, I’ve found that Rebecca Solnit was absolutely right about what society actually looks like when disaster strikes. Los Angeles is not a lawless wasteland where everyone is hoarding precious resources and looking out only for themselves. For a moment there, people became more generous, more unconditional with their love; people were helping neighbors and strangers, unbound by previous obligations or relationships or even the thought of money, just giving and giving and giving because that is simply what you do for your fellow human.

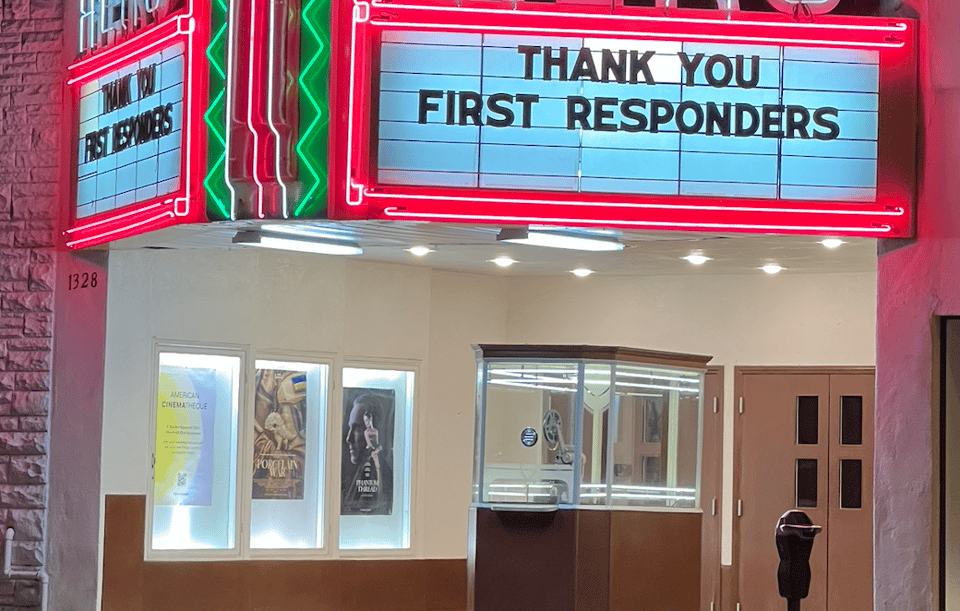

The local restaurants that showed me so much everyday kindness over the years and welcomed me like family opened their doors to evacuees and provided free food and resources to first responders and people displaced by fires. My already generous Buy Nothing group rallied to collect donations for families who’d lost everything. The independent bookstore that fronted me discounts and let me keep a misdelivered book canceled their author events and set up a drive to collect supplies. The saddlery shop that took hours to help out my poor newbie ass (including helping me with gear I didn’t even buy from them) collected and donated tack to help displaced horses and stables. All around me I saw generosity everywhere and none of it was new; I’d been the recipient of so many mundane small acts of kindness in my community and now all this kindness was multiplying upon itself for those who needed it most.

It all made me feel, weirdly enough, like I wouldn’t have chosen to be out of LA when this happened—not because having your home threatened by fire is my idea of fun (it’s something I wouldn’t wish on anyone), but because the sense of solidarity in the air was nothing like I’ve experienced. I’ve been finding it difficult, outside of a few close friends, to talk to people who don’t live here, because they have no idea what it felt like to live through this moment. It’s harder for me to explain what I was feeling—the calm, the faith, the annoyance, the waves of grief and terror and fatigue that hit me long after the fact, the funhouse-mirror aspect of seeing your city’s crisis in the news—to people who didn’t live it than it is to talk to strangers here or scroll through the discussions by anonymous Angelenos online.

It reinforces Solnit's words about the research of sociologist Charles E. Fritz, "that everyday life is already a disaster of sorts, one from which actual disaster liberates us. He points out that people suffer and die daily, though in ordinary times, they do so privately, separately."

Fritz himself wrote, “The widespread sharing of danger, loss, and deprivation produces an intimate, primarily group solidarity among the survivors, which overcomes social isolation, provides a channel for intimate communication and expression, and provides a major source of physical and emotional support and reassurance.”

I wrote this newsletter over several days, not knowing what was going to happen, in a series of scribbles that reflected the grief and annoyance and gratitude I felt at different points as the fires burned, and then after writing this all out I sat on it for almost a week, wondering how terrible I was for writing it all and for potentially posting it. It seems self-indulgent to share such thoughts when, in the end, I was fine. I feel like I somehow stole someone else’s good fortune, and if being rude to the piano store owner made me feel like an asshole, I feel like an even bigger asshole for sitting here, reeking of luckiness, saying that I was scared and sad and grateful and a million other things that don’t matter because I still have my life and my home.

I’m mostly posting this anyway because, well, I haven’t sent a newsletter since December, and so many of you are so lovely about supporting me, and I feel even more like an asshole if I don’t post anything at all. But I also find myself thinking about the fact that this isn’t even the first big communal crisis I’ve experienced in the last five years.

I texted some friends, in the first few days, that it felt a lot like it was March 2020 again: everyone masked, businesses closed, store shelves empty, everyone venerating first responders, and a “we’re all in this together” sense of solidarity between strangers. (A lot of the emails I’ve gotten in the past week have started with “Hope you’re safe,” another throwback.) I thought things were horribly stressful and uncertain then, but the following months and years would excavate deeper depths of disappointment in humanity with the flagrant denigration of vaccines and science, cheapening the sacrifices that frontline workers made for us all.

It’s worth recording, I think, the paradoxical hope that flickers into being when disaster first strikes. I know the long-term ramifications of these fires will be complicated and depressing. I want to remember that for a moment before the ash settled, I saw how good people could be to each other. I think this is worth remembering as we are dragged reluctantly into an era where the people with the most power are the ones who are the most selfish and cruel.

One last time, Rebecca Solnit saying it better than I ever could:

Disaster reveals what else the world could be like—reveals the strength of that hope, that generosity, and that solidarity. It reveals mutual aid as a default operating principle and civil society as something waiting in the wings when it's absent from the stage. A world could be built on that basis, and to do so would redress the long divides that produce everyday pain, poverty, and loneliness and in times of crisis homicidal fear and opportunism. This is the only paradise that is possible, and it will never exist whole, stable, and complete. It is always coming into being in response to trouble and suffering; making paradise is the work that we are meant to do.

-

Sharon, Happy you are safe! You probe your actions and feelings with a deep honesty, and bring your sense of self to a terrible freak of nature/man. I am inspired and grateful for your letters. They are, maybe a bulwark against a terrible uncertainty and growing horror of things already perpetrated by the November election.

Add a comment: