On answering the "What do you do?" question (and failing)

Or, why I just don't tell people what I do anymore

For several years now I have been going to one hairdresser who I love more than some of my own relatives, for the following reasons:

- He knows how to cut Asian hair.

- He has big introvert energy and lets me read entire books during my hair appointments in companionable silence.

- He has no idea what I do.

The last point is of my own fault/making. I’ve been playing a one-sided game since my first hair appointment where I’ve been determined to go as long as humanly possible with this man knowing nothing about a very big, fundamental part of who I am. Once in a while he’ll broach the topic with the gentleness of someone slowly reaching a hand out to a feral cat: “Are you working after this, or do you have the rest of the day off?” to which I’ll say something like “Oh I’m going back to work, but I work from home, so it’s chill.”

I sometimes feel slightly bad afterwards; I’m sure if I told this sweet, respectful man that I play the piano, absolutely nothing would change and he would continue cutting my hair with the laser-focused precision of a heart surgeon. (For those of you now concerned that I am unnecessarily grey rocking him or being the platonic version of an ice queen, please rest assured that we do chat about our families, partners, travel, etc.)

It’s just that over the years, I have started to loathe answering the “What do you do?” question when interacting with normies (one day I’ll come up with a better term for non-musicians). I’ve realized that “classical pianist” is one of those things that people just don’t know what to do with in conversation and despite all the practice I’ve had traversing this minefield, I have yet to develop the social expertise to point the conversation in a direction we can all work with.

Some 90% of the time, this is how the conversation goes:

Them: So what do you do?

Me: I’m a classical pianist!

Them: Oh cool, where do you play?

I DO NOT KNOW WHAT PEOPLE MEAN BY THIS QUESTION. Do they mean “where” like…geographically? I once answered listing a couple of cities I’d played in that year, and then found out that the person’s mental image of “classical pianist” was “person who provides background music in hospitality settings” and they were trying to figure out which restaurant/bar/hotel I played at.

Other times people have some modicum of classical music knowledge (yay!) and deploy it, at which point we both scrabble for it like a lifeline only to crash spectacularly:

Them: What do you do?

Me: I’m a classical pianist!

Them: Oh I love classical music! What composers do you play?

Me: Well right now I’m working on a piece by Fanny Mendelssohn?

Them: [blank look]

Me: You know, the sister of Felix Mendelssohn?

Them: I don’t know them. Do you know Bach?

Me: [wilts] Yeah, I know Bach.

Them: Do you play a lot of Bach?

Me: [trying to salvage the situation by seizing on Bach Things] Yeah, I play some Bach, but you know, I really have to be in the mood for it sometimes, tinkering with all that contrapuntal work can drive you crazy.

Them: [even blanker look]

I don’t know how to be better at this. I think music schools would better serve their students by replacing like, one Theory IV session with a “How to Talk About Your Career in Everyday Social Situations to People Who Don’t Know Anything About Music” seminar. Or maybe this is the real reason why we should be better about funding music studies in public education, idk.

This isn’t even getting into the fact that my work increasingly involves writing, a complication that I have to figure out as the combination of “classical pianist” and “writer,” like bleach and ammonia, creates a (conversational) cloud (of confusion) so strong it’s best for everyone in the vicinity to just vacate the premises. (A lot of people understandably think when a classical pianist says “I’m also a writer” that she really means she composes music, at which point I try to explain that I write with, like, words! and that just creates more confusion.)

It’s much, much, much easier to just not talk about what I do at all if the situation at hand doesn’t require it. (This has occasionally led to hilarious situations, like when I spent an entire day hanging out with someone and neither of us knew we were both professional musicians until a mutual friend brought it up.)

I have gotten super good at answering “What do you do?” with a super flat “Oh, I work from home” in a tone that says “I have a David Graeber Bullshit Job that is so dull it’s best neither of us talk about it because we would die of boredom,” and then we move on to talk about food or pets, at which point I light up and tell so many long-winded stories about how brilliant my cat is that the person then flees from this sleeper Crazy Cat Lady and I am freed from the shackles of social interaction.

Which brings me back to my irrational refusal to let my hairdresser know what I do. I cannot let this beautiful, pure relationship become messy and awkward with confusion and my poor explanations. He has never asked, point-blank, what it is I do, which frankly is one of the best qualities a person can have.

If You Give a Cat a Mooncake

Happy Mid-Autumn Festival, everyone! Because Cleo always tries to eat mooncakes out of our hands (and cries bitterly when we refuse to share) I have now, for two years in a row, made a special mooncake for her out of cat treats and fish. This week I had the presence of mind to film myself making The Cat Mooncake for those who wanted to know how, and then did a quick-and-dirty edit into this video:

Yes, I am a genius, and yes, Cleo is spoiled beyond belief.

The SFS Beat

At this point, if you are interested in keeping up with San Francisco Symphony drama, your best bet is to read everything Emily Hogstad writes on the subject (you can also follow her on Bluesky here). I do get updates via contacts who work under the SF arts umbrella and one friend kindly forwards me the union emails before anything hits the news, but summarizing this all into a coherent narrative on a timely basis is 1) Hardcore Journalism that is beyond my own abilities, 2) a mandate beyond what this newsletter is, and 3) something that other people are doing much better than I ever could.

With that out of the way, the two big things that happened this week:

1) The AGMA members of the SFS Chorus have gone on strike and as a result this weekend’s concerts have been canceled.

2) Whatever is going on with the SFS has broken containment—this week ABC7 (general news for the Bay Area and not an outlet that typically focuses on arts org board leadership) did a story in which the SFS CEO and board chair tried once again to take control of the narrative.

Emily was on it, with receipts. (To quote Joshua Kosman, “Live your life so that [Emily] doesn't come gunning for you the way she's taking down the leadership of the SF Symphony.”)

Geeslin then takes a swing at the PR pinata. She describes an orchestra’s budget like this, in the context of Salonen’s expensive artistic vision:

“‘You sit around a table as a family and you say we have this much money, this is what we can spend this year. Do we take a vacation, do we not take a vacation, do we go out to dinner more, do we do less. It’s saying that this is the money we have to spend and this is how we’re going to utilize it to make sure that by the end of the year we still have a reasonable amount of money to move forward,’ stated Priscilla Geeslin, the Board Chair of the symphony.”

First off, if the stakeholders at the SFS are family sitting around a table, then there aren’t enough seats at that table. The musicians have been trying to sit down at the table for months to start contract negotiations. But for a long time, management refused to set the table: i.e., they put off negotiating, presumably to ratchet up the pressure for as long as possible before the contract expiration date. Meanwhile, dissatisfied audience members are raising hell by holding up signs in Finnish, and have been threatened with expulsion from the dining room entirely.

The whole post is great and you should go read it.

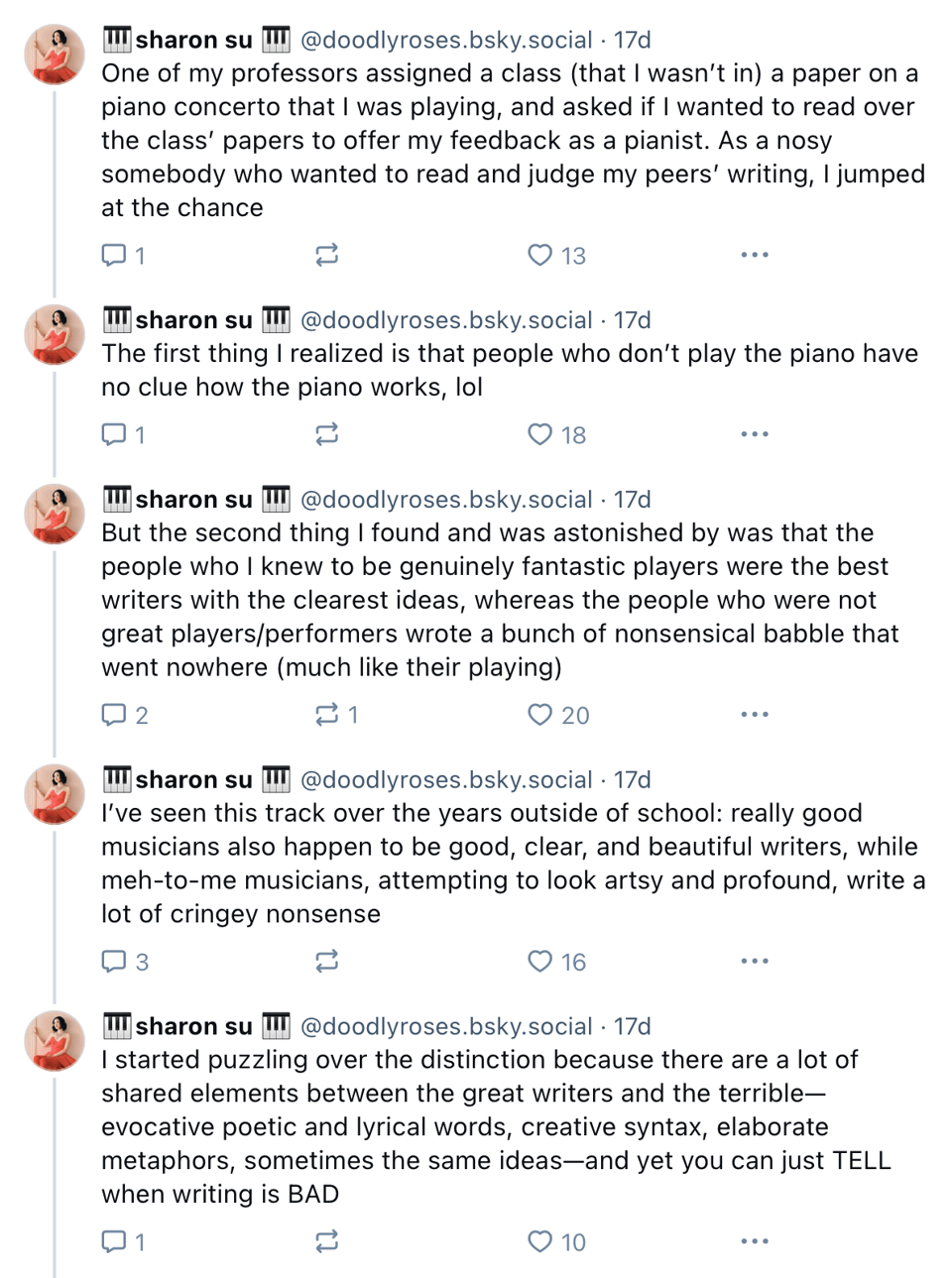

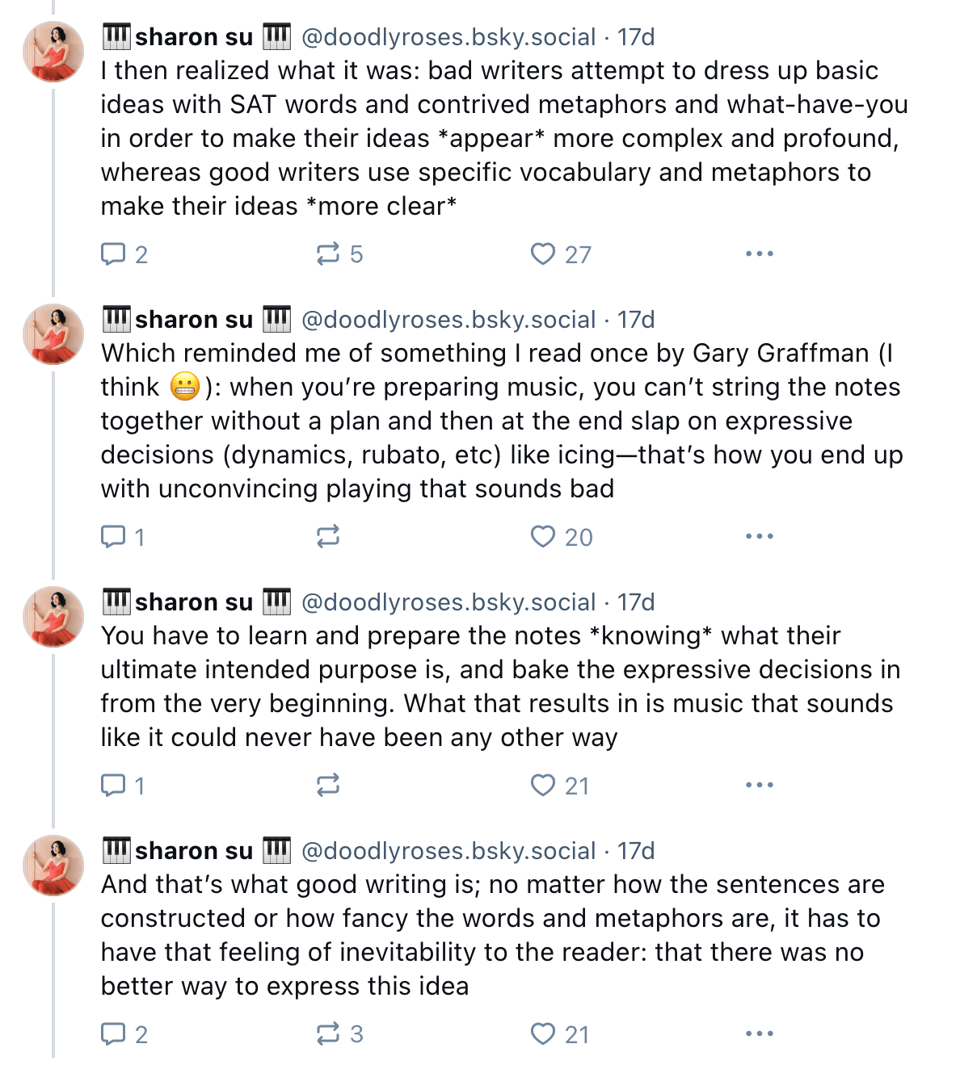

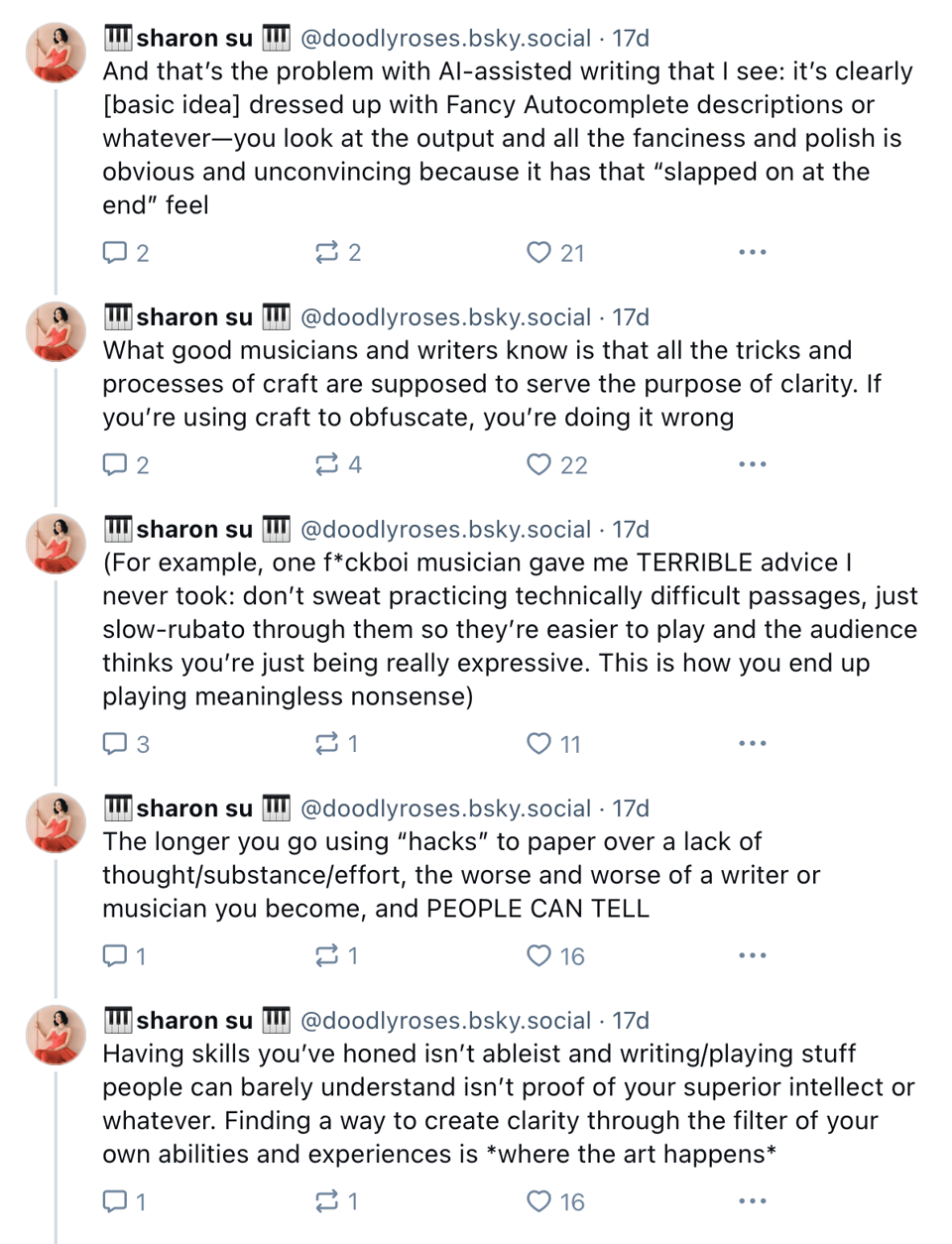

Thoughts about music, writing, and AI

Over on Bluesky I wrote out some thoughts I’d been forming for a while about the links between crafting music and writing. I’m sharing screenshots of the thread here in case you are, for some reason, not on Bluesky:

History is beautiful and also painful

I read two entirely separate (and very well-written) articles that both, to me, encapsulated one of the most beautifully bittersweet truths about history to me: that to truly understand history, you have to steep your whole self in a sometimes overwhelming and painful complexity that cannot be divorced from whatever you consider modern-day reality. There are a lot of people who will, for whatever ends, attempt to sell you on a simplified, child’s-picture-book version of history, and then there are people like the ones profiled in these articles who understand that truth is so much bigger than that.

James Armistead Lafayette’s story encapsulates the paradox at the heart of America’s founding; enslavers who founded a nation to preserve liberty from tyrants. “To get a guest to understand that — to many of them it completely destroys their self-worth,” Seals said. “My job is to minimize their feelings of that destruction.”

That job can require a deft hand and emotional control, as when an older Southern man visiting Colonial Williamsburg with his granddaughter complained about what he saw as the museum’s hyperfocus on American chattel slavery when slavery has existed for millennia. “He’s like, ‘I’m kind of an expert in that sort of thing,’” Seals recalls. “My mind went, ding ding ding! Because that’s also something that I’ve read a lot about as well, which means I can have a conversation.” Seals asked the guest about the realities of enslavement in Greece and Rome, and how those institutions differed from slavery in Colonial America. The differences quickly became apparent. Classical slavery was not hereditary or explicitly based on theories of superior and inferior races, and enslaved people in Greece and Rome had many avenues to attain freedom and become full citizens.

“He actually said to me, ‘I never thought of it that way,’” Seals said. “I didn’t have to embarrass him in front of his granddaughter, which would have completely shut him down.”

In some ways, this was the exchange between two equals that it appeared to be on the surface. But Seals had to do most of the emotional and intellectual work to bridge that divide. At bottom, interpretation is a customer service job, and the power imbalance in favor of the guests is baked in. “Sometimes I’ve got to put myself to the side — actually, most of the time I have to put myself to the side — to think about where [the guests] are and what they need,” Seals remarked.

As with many historic sites, Colonial Williamsburg’s visitors skew older and paler. As of 2013 (the latest available statistics), only 3 percent of visitors were Black.

Portraying an enslaved person as someone whose ancestors were themselves enslaved in order to cater to a largely white audience can be emotionally shredding. In the beginning, Seals told me, the weight of it felt too much to bear. If not for Hope Wright, a fellow Black interpreter, he might have walked. “She saw me unbelievably depressed at the end of it, not wanting to deal with it anymore, and she said to me: ‘Do not bow your head. … It is an honor to give a voice to the voiceless, to humanize the dehumanized. You need to feel honored every single day that you are giving the ancestors a voice that they didn’t have when they were alive.’”

For 24 years, Stewart has led a team of African American divers in Biscayne national park in search of the Guerrero. The Spanish slave ship, caught by the British Royal Navy in 1827, was found illegally transporting 561 enslaved Africans to Cuba. During an ensuing chase, the ship crashed into a reef, splitting in two and resulting in the deaths of 49 people onboard. The exact location of the wreckage remains unknown.

For Stewart, learning about the Guerrero sparked a desire to find the remains of the ship and others like it. In 2005, he founded DWP to train divers in civilian archaeology and assist in documenting shipwrecks worldwide.

“I’ve been on several slave ships, and it’s an eerie feeling,” Stewart says. “Of the 49 who died on the Guerrero, we don’t even know their names.”

Over the years and through a partnership with the Smithsonian’s Slave Wrecks Project, Stewart and his team of divers have contributed to documenting the slave ship the Clotilda, the British steamship Hannah M Bell in Key Largo, and a lost Tuskegee airmen P-39 aircraft in Lake Huron.

In each excavation, the artefacts they find vary – sometimes it’s a cannon, a pulley, or wooden fragments – but the feeling remains the same. They are uncovering remnants of history, literally bringing them to light after hours of fieldwork, surveys and sonar scans. As African American divers, they’re also uncovering parts of their own heritage with each excavation.

Horse Girl Content is Coming

This is a PSA: I have begun taking English riding lessons, thus activating the Horse Girl energy that has lain dormant in me for years.

Yes, my posture is amazing. I was so smug when I discovered that a lifetime of piano playing prepared me for this.

Yes, my posture is amazing. I was so smug when I discovered that a lifetime of piano playing prepared me for this.

A conversation between myself and a longtime friend:

Me: So I’ve started taking horse riding lessons!

Friend: Wait, you were a Car Girl and now you’re a Horse Girl? How does that work?

Me: Car Girl is what happens when you’re a Horse Girl first but you don’t have access to horses.

Friend: Ah.

Just as with my other obsessive interests—sewing, Formula 1—you can fully expect that indulgent writing about the parallels between this and music are incoming. I'm about to become even more insufferable. 🎹

-

As someone who has always spent haircut airtime furiously avoiding any specificity about work, I empathize with that. But I do want to offer the reassurance that saying you're "a musician" seems totally reasonable and normal, and either invites further inquiry or doesn't-- there are so many careers out there that are unfamiliar to others, and in my experience curious people are often genuinely interested to hear about things they don't know much about. At the very least, your job seems easy enough to imagine for most people if you draw the picture for them. (Versus someone responsible for, I dunno, international shipping customs logistics between specific parochial ports.)

-

As a non-musician who spent a summer cooking for the Marlboro Music Festival in 1970, I am well aware of how little I knew then and how much less I know now. I talk much more fluently than I write, but someday when we are in the same vicinity on the planet, I would like to share some "outside - in" stories about the graceful ways the players (especially Felix Galimir) were willing to help me see further into their world.

BTW - I am now retired in Freeport, Maine (should you ever want a free bedroom and to visit LL Bean) and my retirement gigs include being an assistant piano mover for George Family Piano in Harpswell, Maine, as well as softball umpiring, the usual run of community boards and as a member of the Freeport Fire Rescue Fire Police (which gave me an excuse to put a set of flashing red lights on my 20 year-old Land Rover).

Add a comment: