Distillations/Constellations #8: double standards

I’ve found that a good litmus test for rooting out prejudices is the following: would people be comfortable with [situation], if their friends or family were involved?

When I was working on attempting to undo or redirect biometric systems which unnecessarily collected masses of personal data, I asked people involved in building the system:

Would you be comfortable with your friends or family appearing in this database? Having their fingerprints and iris scans included, to be shared with an unknowable amount of government and non-governmental agencies?

The answer, somewhat unsurprisingly, was almost universally: “No.” The explanations were often revealing. Reasons like: “Because I don’t know who might have access to it, or what they might do with it.” or “Because I don’t want my children to be recorded or associated with this.”

Somehow, these concerns hadn’t been a problem when thinking of millions of “others” – in particular, others who didn’t look like them, or others with whom they didn’t seem to feel any affinity.

Recently, I’ve found myself using a different version of this litmus test. I’ve been asking white German people:

Would you feel the same about what’s going on in Palestine, if it were happening in a European country? If the same level of violence and horror were happening to people who look like you, do you honestly think that there would be this level of apathy and inaction that we see today?

Without a single exception, everyone has said “no.” I’m simultaneously grateful for the honesty, while also being (naively) horrified at the prejudices this reveals. I’m reminded of this podcast episode from 2020, where journalist Mehdi Hasan broke down all the ways in which Islamophobia showed up in the world leading to a “global surge in anti-Muslim bigotry, often supported by the full power and might of the state.” It struck me then how impossibly coordinated it all was – Islamophobia showing up in countries distant from each other, on a state and community level, and how scary and dangerous that could be. That was four years ago.

Yesterday, I read this article (in German) which outlined a level of othering and prejudice that I (again, naively) didn’t think was possible.

Here’s a summary, which makes me feel sick to the stomach to even write: Seriously injured children from Gaza were offered fully financed trips to Germany to treat their injuries, with doctors and surgeons in Germany offering to treat them pro bono. As the author, Natalie Amiri, describes, the youngest child at that point was 3 years old. A girl named Ronza. And the German authorities… did nothing, at first. Bureaucratic hurdles, lack of responses. Then the Ministry of Interior finally responded, to say that the children should travel alone, without an accompanying adult, for security reasons. It’s unthinkable for heavily injured children to leave their home country, their family, to travel to a foreign country to receive life changing surgery, alone.

This level of inhumanity is just incomprehensible to me. It’s a sign of complete othering, of seeing those poor injured children as less than human – that I can’t comprehend.

This podcast episode from the Othering and Belonging Institute explains more about the psychosocial side to othering and introduces a model, first developed by Professor Susan Fiske at Princeton University, called the Stereotype Content Model.

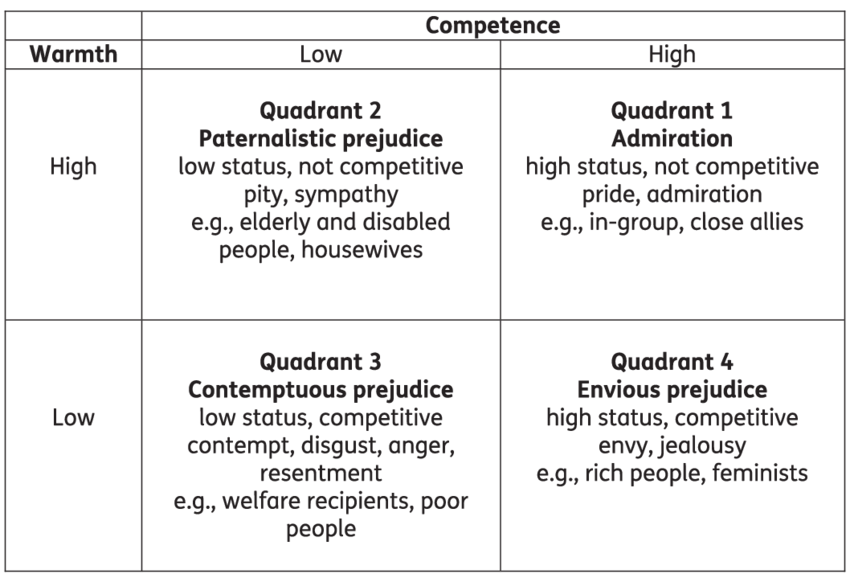

In the podcast episode, john a. powell describes how this model helps visibilise prejudices in different contexts. He says: the “gold corner” is Quadrant 1, where you think people are highly competent AND you have a high degree of warmth towards them. The “most disparaged” group is Quadrant 3, where someone is considered as “not fully human.”

The Othering And Belonging Institute considers ‘belonging’ as the opposite to othering: moving people from Quadrant 3 into Quadrant 1. I can’t help but wonder what policies and technologies would be developed if everyone was Quadrant 1: seen as competent, as warm, as belonging, as deserving, from the very beginning.

What I’m reading

This report on Endowing the Future, by CIVIC SQUARE: CIVIC SQUARE is an organisation I’ve admired from afar for a long time – they’re a place-based organisation “demonstrating neighbourhood-scale civic infrastructure for social and ecological transition, together with many people and partners in Ladywood, Birmingham UK.” Things I appreciate from this chapter of their report include their call to “invest in possibility, knowing that it is unlikely for change to happen linearly with advance warning” and a call for “at least some of the wealth held by philanthropic institutional and individual wealth-holders being moved to ‘real world endowments’.”

I’m late to the party, but Naomi Klein’s latest book, Doppelganger. I really love this style of non-fiction book, which combines personal narratives with structural political analyses, reporting and research.

Achieving Transformative Feminist Leadership: A Toolkit for Organisations and Movements, written by Srilatha Batliwala and Michel Friedman for CREA. There’s a lot in there to take away, so here’s just one nugget: the four P’s of leadership, mediated by the self – Power, Purpose, Practice and Principles. And this, which I feel too often gets missed with the daily grind of running an institution: “As feminist leaders deeply concerned with the transformation of power inequalities, we understand that we have to engage in transformational work within ourselves, as we are instruments of power in our own organisations and movements.”

Add a comment: