I read a sentence in a paper about cell contraction during gastrulation that made me tear up a little today, which just kind of illustrates the level of underwater I am right now. This year, seven whole years into my PhD, I've finally figured out why it's so hard for me to care about other things: it's all my horrible, horrible thesis' fault.

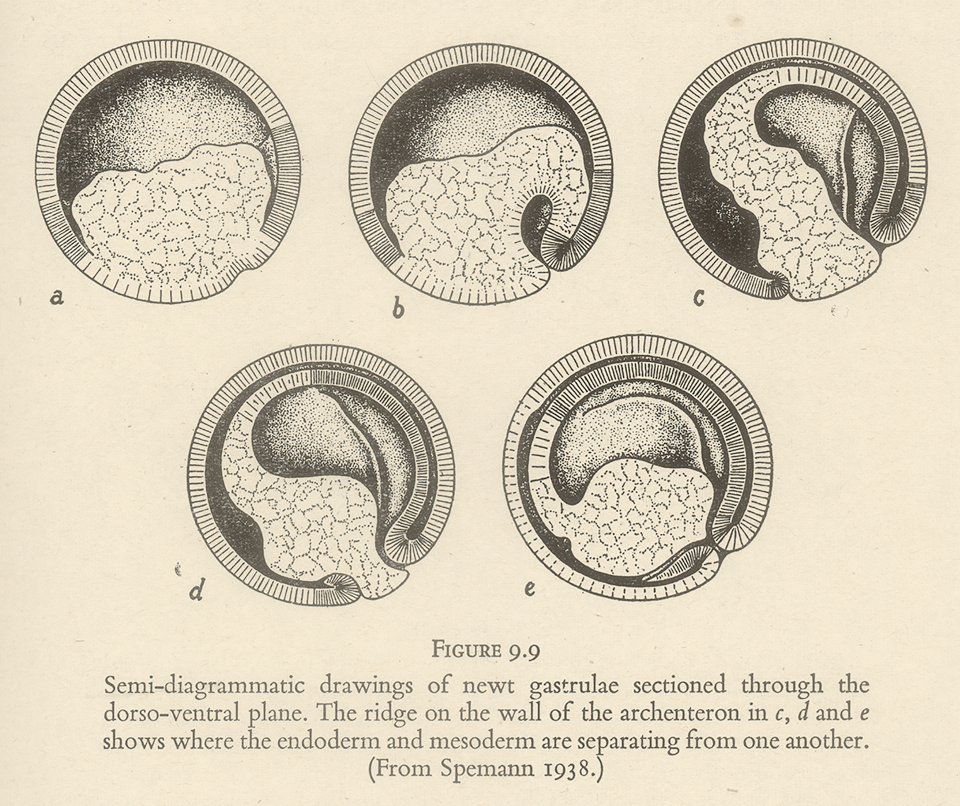

The paper begins by describing cell contraction. Cells, during the early shaping of the primordial stuff of an embryo, like to contract. They contract a lot, contract often, and do it at very specific times and magnitudes. This is how tissues are shaped. This is how you get a brain instead of a butt. One sheet of cells decides to get smaller on one side and fatter on the other, and suddenly you have a spiral, which means more layers, like folding pastry dough. That's gastrulation, baby. We're layers all the way down. As Lewis Wolpert liked to say, "It is not birth, marriage or death, but gastrulation which is truly the most important time in your life." Not sure about that, but it's catchy as dicta go.

Back to the paper:

"A key discovery in the last decade of work on these processes is that they are often pulsatile in nature, with highly transient actomyosin populations that briefly apply a tensioning force to an area of the cell cortex. This has raised a central outstanding question—if actomyosin networks display such pulsed behaviors, how does processivity emerge from cyclic systems? To obtain lasting changes from such systems, there is a requirement for ratcheting mechanisms that gain irreversible changes out of periodic, contractile cycles."

In other words, how do you build something out of a pulse? How do you sail out of a tide? How do you generate lasting change out of oscillatory structures? How do you keep the wet organic mess from sloughing apart between every heartbeat? This is true for fruit flies. It is true for solitary migrating amoeba. It is true for humans.

This is something I take for granted, but shouldn't. At the cellular level, we are shockingly similar to fruit flies. Our cells look much the same. Our gastrulations follow roughly the same paths. We metabolize. We contract. We grow. As a cell biologist, when I watch the early embryos of fruit flies, I feel like I'm watching myself too. Something something god emotion, but not in that feeble Christian way.

Another quote from a review written by the same lab:

"As force generation is pulsatile, to achieve an irreversible change in cell shape the elastic properties of the cells must be overcome and a viscous response occur which will then permit a lasting deformation."

Elasticity against viscosity. Living cells, especially when those cells are taking their places in the serenely blank canvas of the early embryo, are highly elastic. They undergo monumental movements, ripple and fold within minutes, a gorgeously precise choreography that has been embellished upon for billions of years of evolution.

There are a couple wild ways the elasticity of tissues has been measured, at least in fruit flies. My favorite is attaching a disc of tissue to a clamp and just stretching it out, like a piece of wet gum. You can really just keep stretching out that tissue! Something a bit more boring is using optical tweezers, shining an intense la Or, another favorite, injecting ferrofluid into the embryo and jiggling it around with an external magnet.

This is something I'm obsessed with lately. How when one wave falls, another rises. How synchronicity matters. How everything on the cell and in the embryo must find its proper place before the next wave rises. How precise the line is between life and no life. Between an elegant creature emerging from its pupal case, and a tumor.

You just read issue #16 of Dear Ghost. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.