What makes the green bond green

I talked to a superintendent the other day. I met him on twitter when I was trying to put together an illustration of how school bonds work and asking for help (see below). He said he'd be happy to talk to me on the phone to walk me through his experience. When we talked, he said he appreciated that fact that I was putting that slide together since, in all of his training to be a school leader, no one talked to him about bonds, even though they'd turned out to be a cornerstone of his work as an upper-level administrator. He said talking about bonds is important for material reasons: since he didn't have any knowledge about them, he was forced to trust whatever financial advisors and business managers told him. This made it harder to make decisions and to know for sure whether he'd be saving taxpayer money or spending it poorly.

We know that there's an information gap between school leaders and finance experts. Amanda Kass, Martin Luby, and Rachel Weber have a great paper on how that gap cost the Chicago Schools $100 million when they decided to buy swaps in the early 2000s, all of which tanked in the 2008 financial crisis. If school leaders had more knowledge and information maybe they wouldn't have let that happen.

I got my opportunity this semester to put this lesson into practice. I started teaching in a new principalship program this year. These programs prepare students, who are mostly veteran classroom teachers, to be principals of school buildings. My class looks at legal and financial issues. The director of the program told me to make sure that students know how budgets work, but other than that I had free rein. So I decided to make the first half of the course about budgets and the second half about bonds.

One my favorite parts of teaching teachers about education is assigning presentations. I ask students to do a presentation about some legal, financial, social, or economic aspect of their school districts. I always learn a ton and students get to analyze the complex social conditions they live in every day. I also try to take advantage of this opportunity. In every class, I give an example presentation on the Philadelphia school district to show students what I mean and also do some digging into my own school district. For the second half of my principalship course, I decided to do a presentation on a green bond that the School District of Philadelphia issued last year. I wanted to know what makes a green bond green, but also what it means for a school district to issue one. I like to make myself a student in my classes and indeed, I learned a lot by doing this presentation.

Why not more?

According to Investopedia, “a green bond is a type of fixed-income instrument that is specifically earmarked to raise money for climate and environmental projects. These bonds are typically asset-linked and backed by the issuing entity's balance sheet, so they usually carry the same credit rating as their issuers’ other debt obligations.” These bonds are getting more and more popular. Climate Bond Initiative reports that more green bonds got solid in the first quarter of 2021 than all of 2015 combined.

That year, the School District of Philadelphia was one of these sellers. It closed a deal on a bond worth $370 million and proudly announced this on its website on October 7th. This is good! The district has a pretty solid track record of thinking greenly when it comes to its buildings. From an early award for one school's initiative in 2013 to a major district-wide energy savings plan since 2016, the district is trying to do more green projects on its schools.

So when I saw the green bond from 2021 I had a question. It turns out the $370 million isn't all in green bonds. Only $60 million is. Again, that's cool--but why not do the whole bond as a green bond? And why not issue all projects as green projects form here on out? There are some details that probably get in the way here.

It's (not) easy being green

As I've written about before, districts have to bid for construction contracts. They don't have in-house construction firms that do the work for them (though that would be neat). There are all kinds of laws about this bidding process, including whom you can bid to and which bids you can accept when you're a public entity like a school district. For instance, you have to take the lowest reasonable bid when doing construction contracts. This helps prevent corruption, inside-dealing, etc.

But when it comes to green projects, there's a law called the Guaranteed Energy Savings Act (GESA) that provides some flexibility in the construction contracting process. GESA is a kind of procurement law that lets apparatuses like school districts insert clauses into their contracts and thus the bidding process that makes it easier to complete projects that reduce energy usage. The Pennsylvania Department of Education administers the school district version of this program.

The Guaranteed Energy Savings Act allows governmental units to ignore other contrary or inconsistent laws when entering into contracts with qualified providers. School districts have the option of soliciting construction offers through the “Request for Proposals” process outlined in the Act, or by going through the normal statutory process for school construction projects including competitive bidding, separation of contracts and awarding of contracts to the lowest bidder.

This helps school districts do green projects. In Pennsylvania, you need to get Department approval, so that could slow things down I suppose. But the bond statement says that Philly has been working on GESA projects for a few years now. The first group of these projects was called GESA-1 and the $60 million from the 2021 bonds will go towards projects in that plan. At the end of the statement, the district includes an addendum--always read bond statements, and always read the addenda--called Addendum G. This is a single sheet that lists the kinds of projects the green bonds will finance and which schools will get work done.

It's always interesting to which schools they're going to do work on, particularly for green projects. A couple things caught my eye here. The first is that HVAC is first on the list of kinds of projects. I wonder what the carbon footprint of HVAC systems is, particularly in old schools. I have to look that up.

Then, on the list of schools, the first one stood out to me. Last year, students and teachers at SLA-Beeber took to the streets to protest the reopening of their school building. They didn't want to go back given the unsafe conditions of the facilities. The district actually relented and sent an emergency order to keep the school online.

The emergency order came in response to an ongoing construction project at SLA Beeber that has left the school with exposed damaged asbestos, thick layers of dust, and a lack of adequate indoor bathrooms for the 700-plus student body. (The district had brought in outdoor portable toilets for students.)

I don't know if SLA-Beeber was on the original GESA-1 list of schools, but at least this confirms that the district is doing something green about the problems with the building.

There were some other eyebrow raisers in this bond statement. One of them was in the description of how the funds will work. The district says that the money for the green bond will be put in a "segregated account" separate from other monies. That's all it said: segregated account. I had some questions. What's the deal with this segregated account? Are there other compliance issues with it? Is it for GESA? I know that it's usually rightwingers that get concerned with inefficiency and corruption in local government, but I think socialists should be concerned with it too. Then I saw something else I didn't like.

Cut off your Johnson Controls

The bond tells us which companies the district will work with on the green projects. It reports that Johnson Controls International (JCI) will be the main contractor. JCI is a buildings maintenance firm with an otherwise innocuous website. The district contracted $8.6 million of work with them last year. Looking up the company's history, I saw that as recently as 2016 the company was called simply Johnson Controls. Then it merged with an international company called Tyco and moved its base of operations from the United States to Ireland. Why? The corporate tax rate is much lower in Ireland and the company wanted to take advantage of it. In fact, it has not paid $150 million of US taxes per year by moving from the US to Ireland.

This move isn't looked kindly upon by everyone. Merging with another company internationally and then moving to get a lower corporate tax rate is a form of tax inversion. In 2016, when JC became JCI, Hillary Clinton of all people called the move outrageous. I wondered if the district is okay doing business with a company that decided it didn't want to pay taxes? Maybe someone in the Office of Capital programs has a connection to them?

The whole thing with JCI is an example of what doing green bonds means: it means green capitalism, which brings to mind another thing in the world that is associated with the color green. Money. Is a green bond helping the environment or helping capitalism? Looking at other aspects of the bond really bring this green problem out.

Green is the color

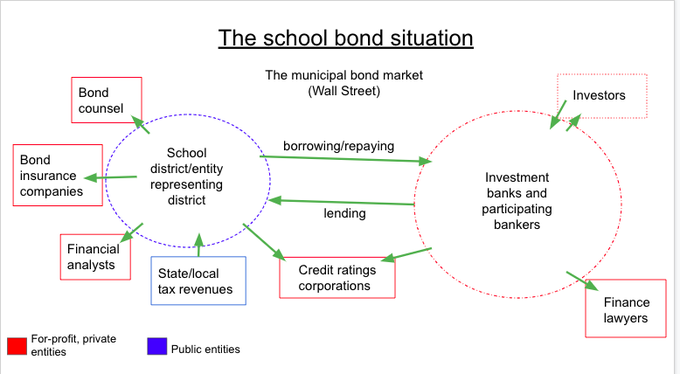

Bonds involve a whole bevy of lawyers, consultants, and agencies that take a cut of the money going back and forth between investment banks and school districts. Like I said at the start, I made a slide illustrating how money flows in a school bond generally for my students and thought I'd throw it in here. The green arrows track the cash flow.

Philly's green bonds from last year are no exception. The district needs to pay a special bond counsel lawyer to make sure the deal is legal. This firm is called Eckhert Seamans. Then there are the banks. At the bottom of the first page of the bond statement is a list of all the investment banks involved in the deal: Siebert Williams Shank & Co, LLC; AmeriVet Securities; Barclays; Bank of America Securities, LLC; PNC Capital Markets; Ramirez & CO; and RBC Capital. The first bank, Siebert Williams Shank, is in big font above all the others. I recognized the name from other bonds I'd seen from the district. There's a thing about Siebert that makes me mad.

When you look it up, the news articles all talk about how it's one of the biggest investment banks run by white women and people of color, not just white men. The CEO is a Black woman, for example. I suppose we should applaud Siebert and the district for contracting them to the tune of $716,000 last year.

I'm for race and gender justice. But is it race and gender justice when white women and people of color are at the helm of an apparatus that's forcing thousands of kids of all races and genders to attend toxic schools? As I've written about recently, toxic finance leads to toxic school buildings. Is it race and gender justice when an ultra wealthy Black woman runs an investment bank that indebts a school district serving the diverse working class of Philadelphia, a majority minority city, whose school buildings are poisoning teachers and students? I don't think so.

Yet the money that Siebert helps front for the loan to the district will go towards greener school infrastructure. That's one of the tensions at the heart of the green school bond: which green is it?