What happened in Vermont

Carol Brigham’s family stopped talking to her. The superintendent of her school district got his tires slashed. A father, reporting on what was happening, had to explain to his daughter why their neighbors were calling them sharks. The popular fiction author John Irving felt his children were being threatened by ‘trailer envy’, pulled them out of their public schools, and started his own private school using his own money.

It’s Vermont in the late 1990s. An inspiring school funding system has been put in place by the state government. Brigham and others took on the state’s wealthy property owners and won a rare victory. The reaction was intense.

What happened here? What was the system that caused such distress among the Vermont’s ruling class? And how did they successfully kill it?

The cruel illusion of local control

Carol Brigham’s local school, the Whiting School, couldn’t afford a new roof. It couldn’t afford the extra teacher students needed. They couldn’t afford it because they couldn’t wring enough revenue out of their low property values. Just across the Green Mountains, Kilington schools had more money than they knew what to do with. That’s because Kilington is a ski town with high property values. It could spend 25% more per pupil than Whiting.

So Whiting’s superintendent worked with a coalition of other districts to sue the state government for being in violation of its own constitution, which guarantees an education to all its students. Carol’s daughter Amanda agreed to be a plaintiff and the case was named after her.

The inequalities in Vermont were really bad. Average per pupil spending was nearly $15,000 in rich towns and less than half that in poor towns, at $6,500.

The court found in their favor. It was kind of intense actually. Judge John J. Meeker skipped the appeal stage and wrote a scathing opinion. It’s worth a read. The best line, I think, is when he calls local control a “cruel illusion,” since districts where property values are low don’t have control over the education they provide. ‘Local control’ is only for the rich districts. Still true.

As happens with successful school finance equalization court cases, the judge ordered the state legislature to come up with a new funding structure. Unlike New Jersey, where lawmakers dragged their feet, Vermont legislators got busy and passed something very strong very quickly.

Marxist Robin Hood gone wild

The result was Act 60. In my research thus far, it’s the most confrontational school finance law when it comes to private property. People in rich towns called it Marxism, leftism, and Robin Hood gone wild. And they were kind of right.

Here’s how it works.

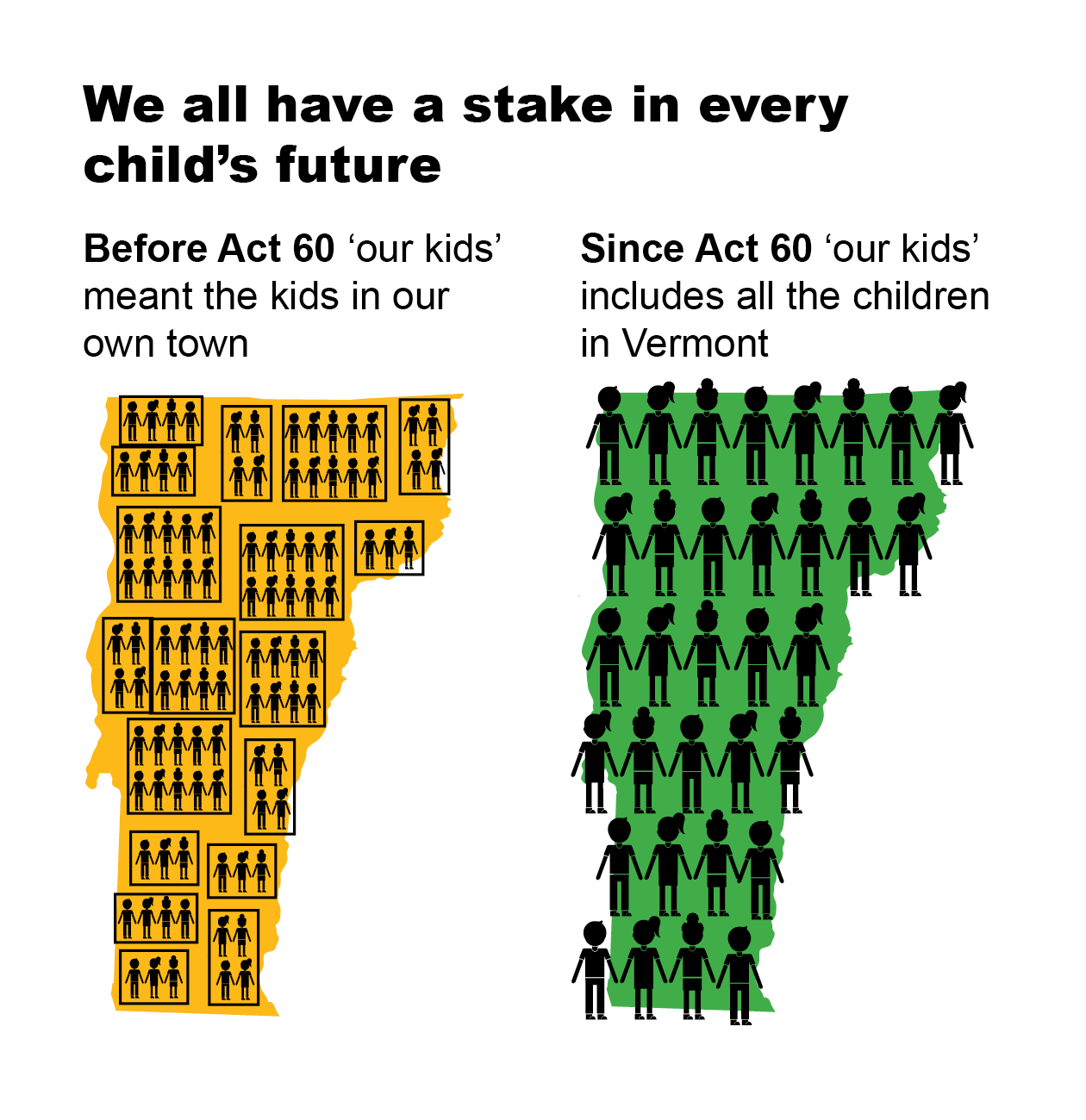

Every district levies a property tax to fund its schools. When you have districts with high property values, they can tax less and get more. Districts with lower property values have to tax more to get less. Siloed into the dog-eat-dog, individualistic, illusion of ‘local control’ it’s everyone for themselves.

But Act 60 set a state standard for property tax rates. Every district had to tax their property at about one dollar for every $100,000 of assessed value. At the same time, the state calculated funding allotments to each district. Any amount of revenue a district raised above the state allotment went into a statewide pool and got distributed to poorer districts.

This is brilliant, because it forces the rich districts to tax their property at a relatively (though not outlandishly) high rate, and then, given the state allotment, captures excess revenue to redistribute. It milks the rich districts. It also ensures that poor districts don’t have to tax their property overmuch. They get what they need in terms of school funding. Rich districts became ‘giving towns’ and poor districts became ‘receiving towns’.

Turns out Marxism is good.

At the height of its powers, Act 60 equalized the tax burden. Before Act 60, average town tax burdens varied from .1% to 8.2% on assessed property. After Act 60, they ranged from 2-4%. Average differences in per pupil spending between districts went from 37% to 13%. Districts that had historically spent less increased spending at a greater rate than districts that had spent more.

But in the end, school funding equality isn’t good for its own sake. It’s good because it’s good for students. And Vermont’s acheivement gaps closed between 1998-2001. (All my info is coming from this essay, btw.)

As you’d expect, the King came for Robin Hood.

Ruling class claps back

When you confront wealthy property owners, they come at you. The same happened with Act 60. Rich people went bonkers. They slashed superintendents’ tires, put up ropes blocking roads to their neighborhoods, and called towns like Whiting shark towns. It was class struggle par excellence.

Ruling class blocs don’t mess around. They get creative and get organized. In the giving towns, wealthy people formed private foundations and donated ‘voluntary levies’ for their schools. This meant the money couldn’t be recaptured by the state and shared. They basically created a parallel privatized funding structure. They formed alliances, initiatives, and organizations that supported these foundations. One example was the Freeman Foundation of Stowe, which promised to match any district’s private fundraising each year. In all, they matched $20 million of private voluntary levies.

The Freeman Foundation was a powerful organization in Vermont. And guess who was too scared of them to stand up to them? Then Governor Howard Dean. He ended up saying Act 60 didn’t work and sided with the Freeman. I didn’t like him much before, but now I really don’t. His Lt. Governor, Racine, was for it though. Dean called him a misguided whiner. (Ugh.)

Act 60 was at the center of the 2000 gubernatorial election. It was very close but the Republican, Douglas, won on a promise of making ‘struggling taxpayers’ whole. Act 60 was largely gutted when Act 68 reformed it. The new law got rid of the sharing pool, its most confrontational protocol. It left some things in place, so Vermont’s not awful in terms of school finance, but Act 60 became a thing of the past.