Twoers and Seveners

You can learn a lot when leftists disagree in public. The cover story for the January 2018 issue of In These Times was "Wall Street Isn't the Answer to the Pension Crisis. Expanding Social Security is." Doug Henwood and Liza Featherstone, heavy hitters on the left, wrote the piece saying there's a pension crisis. Henwood even went on C-SPAN to talk about the article.

Then pensions researcher Max Sawicky responded to them in the magazine, saying no, there's no pension crisis, and that Henwood and Featherstone's recommendations were misguided. Henwood responded, saying yes, there is crisis. Sawicky responded again, in a fourth piece for Jacobin, saying no, there is no pension crisis.

This debate wasn't specifically about teacher pensions but it's helpful for understanding what's happening with teacher pensions and what, if anything, we should propose to change about public teachers' retirement policy from a left perspective. I can't do the whole debate justice, so here's a breakdown of some of the main contours I'm seeing.

Is there a crisis?

A big question at the heart of Henwood/Featherstone and Sawicky's debate is whether there's a problem with public pensions at all. Over the last few weeks, I've written about different perspectives on this question and tracked their datasets and ideological tendencies.

Overall, I've found that rightwing neoliberals tend to point to a pension crisis. They focus on cost increases, arguing that these costs are unsustainable and taking too much money from other things. They tend to recommend replacing defined benefit plans with defined contribution plans. They also tend to be anti-union, get their research funding from anti-union, market-zealot organizations, and therefore want as much public spending and policy to be more market-oriented.

Henwood and Featherstone actually agree that there's a pension crisis. But they have a totally different ideological project than the neoliberals. They want retirement policy out of markets entirely. They'd rather get rid of pensions whole hog in favor of a more robust social security system. They cite McCarthy's book Dismantling Solidarity and harken back to the days when social security was supposed to be our big, public, and federal retirement program rather than the decentralized industry-specific pensions we have today. The system of pensions we have now were always a compromise when moderates (and actually unions!) defeated bigger and better public program to deal with old age in the 1950s.

Henwood and Featherstone make their leftwing cost-side argument by focusing on the unsustainability of pension needs. Drawing from my previous posts on this, whereas Chad Aldeman gets his data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and Equable, Costrell gets his data from the CalSTRs pension, and Biggs gets his data from the PPD database, Henwood and Featherstone get their numbers from the Federal Reserve.

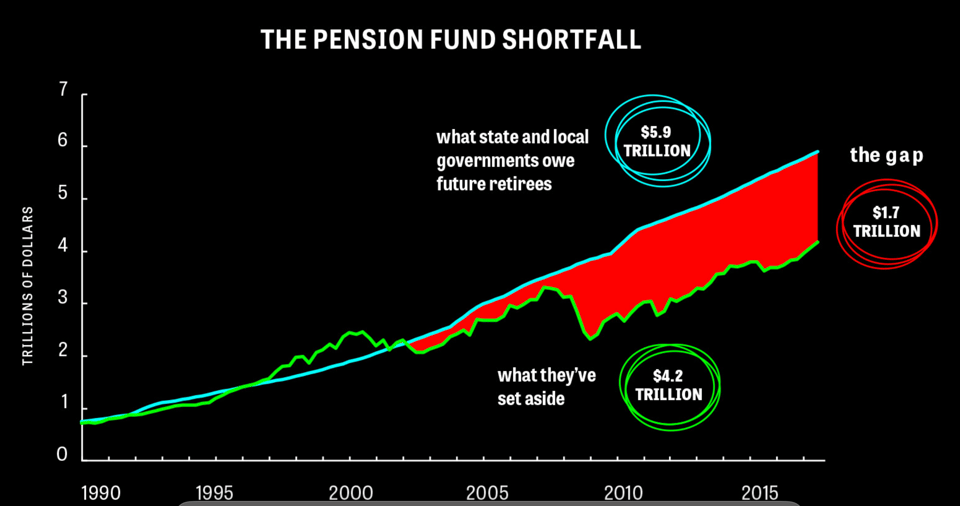

Governments have promised trillions of dollars to present and future retirees—$5.9 trillion (according to Federal Reserve statistics)—to be paid out sometime in the future. Unfortunately, they don’t have anywhere near that kind of money, either on hand or in the foreseeable future. Crisis-driven cuts have only made the situation worse. The Fed has calculated that, all told, the nation’s pension accounts are $1.7 trillion in the hole—and others put the shortfall at closer to $4 trillion.

They have their own scary graph to illustrate what they call "the gap."

This looks bad. But let's think about it for a second. In terms of having enough money right now, Biggs, in his study of 31 teacher pensions, has already told us that teacher pensions are not at risk of insolvency. The claim that Henwood and Featherstone are making though is that pensions generally don't have enough money to pay out their retirees' annuities over the next few decades, which, despite pensions' current solvency, remains an open question.

Why is it an open question? Here's the rub. If you listen to Henwood's CSPAN interview, he talks about investments a lot, Wall Street, stock and bonds, and the performance of the stock market. It turns out that your position on whether pensions are in crisis depends on how you think about Wall Street investment performance over the long term.

Tea Leaves

Pensions are huge pools of capital made from contributions paid by past and current employees. These funds pay out annuities to current retirees right now in the present, but the funds have to do this for future retirees too. The pensions are managed by investment experts who buy and sell stocks and bonds using the pension's money. Their goal is to bring in returns that will keep the pension fund in good shape over time so that the pension can keep its promise to every future retiree.

To manage the pension, these people have to read a lot of tea leaves. Will the pension investments make good returns? How will the stock and bond markets perform? To research the pension and assess whether that pension can keep its promise, you have to argue for your interpretation of those tea leaves. When we ask whether the pension won't be able to pay these benefits at some point in the future, whether distant or near, we have make some assumptions about how much pensions can make on their investments in stocks, bonds, etc.

No one knows the future. The leaves can tell many stories. But we can make assumptions about the future to do our best when we plan. Are public pensions' assumptions about future returns bad or good? If you think they're bad, then you think that pensions are in crisis. If you think they're good, then you think pensions are fine. That's where Henwood/Featherstone and Sawicky disagree.

2s and 7s

Henwood and Featherstone cite a Stanford economist who found that public pensions assumed a 7.6% return on their investments. Henwood/Featherstone call that assumption "recklessly optimistic" given poor market performance before and after the 2008 financial crisis. They recommend that pensions should assume the return that a standard Treasury bond gets, which is much more conservative. Those bonds get around 2.5% (this was in 2018, before the Fed increased rates!). When you assume that pensions will get 2.5% return, the cost crisis become alarming: the pensions won't be able to pay out their annuities if that's what they're gonna make from the market.

Costrell makes a similar case, showing that CalSTRs only had a 5.8% return on their investments between 2001-2019. While Henwood and Featherstone think anything above 7% is recklessly optimistic given the stock market performance, they also mention that while 2.5% might be too pessimistic, it's a better way to think about the whole situation given how bonkers the market is.

This is basically where Sawicky hits them. He says there's no reason to assume market conditions will be that bad. He also says that if you look at public pensions from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) lens (rather than the Fed, PPD, BLS, etc), there's no reason to panic--indeed, there's no crisis with pensions if you don't make these assumptions. They're not insolvent. There's no risk of them losing money.

Along with their assumptions and dataset, Sawicky also disagrees with the politics and ideology of Henwood and Featherston's argument. He doesn't like the left being in league with neoliberals and rightwingers bent on destroying unions and privatizing pensions. He also doesn't think a big, public social security program is feasible policy to propose as a demand. Bernie Sanders's electrifying campaign was only two years old at that point, and Henwood and Featherstone may have gotten caught up in the excitement, and Sawicky is skeptical. Why put the pension programs we have on the chopping block in favor of a pie-in-the-sky policy? Sawicky recommends supporting pensions as they are, protecting them from rightwing attacks, and making them serve the working class better than they do.

Rather than a cost or contribution line of demarcation in this debate, it's more about whether you're a 2 or a 7--that is, whether you think it's better to assume a two percent market return or a seven percent market return. Henwood/Featherstone are twoers and Sawicky is a sevener. I think Sawicky has a point here: Henwood/Featherstone's approach is some eleven-dimension chess where they use rightwing talking points to advocate a leftwing project. Why not lead with the leftwing project, why even mess with the rightwing talking points? Doesn't that cede them crucial ground?

The political economy of assumptions

But I kind of get it. Let's think about the ideology here. Henwood/Featherstone assume a 2.5% return because the stock market hasn't been doing that well and probably won't do that well in the future, yes. But they're not just making this pessimistic assumption about market performance because they think the stock market will behave poorly. They don't just want pensions to be solvent and efficient. They're not citing rightwingers because they agree with them. In the grand scheme of the dialectic, they think it's a bad idea to tie people's old age money--society's future generally--to rapacious financial capitalism.

Henwood and Featherstone are socialists. They don't trust capitalism to provide a stable, generous, humane, or moral mode of exchange and distribution for the social risk of aging. They're ultimately making the case for a big, public social security program at the federal level that will supplant the pensions predominant now. This perspective comes through when they tell some wild stories about how pension investments actually undermine workers' rights and lives. Here's one of them.

Kohlberg Kravis Roberts was a private equity firm that bought the grocery chain Safeway in the 1990s. They cut 63,000 working class jobs when they closed stores and restructured the company so it was profitable. They made $7.2 billion on their $129 million investment. Where'd they get that money? Partly from investments made by Oregon, Washington State, and Michigan public pensions. The public pensions put in money and got back good returns. They made some money for their retirees' annuities, but that money came from the pillaging of grocery store workers.

Stories like this abound. The political economy of Henwood and Featherstone's market assumptions is important to think about. Shouldn't socialists want old age policy out of the rapacious market? We shouldn't take from some workers to give to others, they say. When they cite rightwing economists on the pension crisis, they're doing this to advance a larger socialist project, which turns the market ideology behind those claims on its head.

But Sawicky is also advancing a socialist project by being more realistic. He takes on the political economy of these market assumptions by suggesting that pensions are invested in all kinds of things, and these kinds of terrible stories could be found in any instance of investment. Why hurt workers by telling these stories and putting their pensions at risk? (I made a similar point when writing about Costrell's recent argument about risk: since we don't dig into all the actual pension investments, we have to make assumptions about the portfolios, and we imagine them with ideology.)

Thus the Henwood/Featherstone-Sawicky debate is more about a tension between idealism and realism in socialist understandings of pensions. Henwood/Featherstone are being idealistic when they take the twoer/cost-side perspective because they want a big social security program. Sawicky is being more realistic when he defend a sevener position against their more strident claims.

Next week, I'll lay out a proposal that I think takes from each of these positions. Stay tuned.