To schools themselves

Quick Links

Advait Arun wrote a thoughtful review of my book for his substack at The Crow’s Nest. He really gets what the book is all about politically, financially, personally, ideologically.

Check out the Building Power Resource Center’s new report on Salt Lake City School District’s green infrastructure, aptly titled “Saving Millions and Cutting Emissions.”

I wrote a post for The New Press about why we need an elected school board in New York City.

I was shocked and terribly saddened to learn of the untimely death of Asad Haider, a friend and comrade. Here’s a moving set of memorials to him.

Now to this week’s post…

In the first week of December I was invited to address a school’s parent-teacher association. Specifically, their advocacy committee had me and a fascinating group of education policy folks from throughout NYC’s DOE-sphere talk to parents at their school about the new landscape of education politics after Zohran’s victory.

The meeting was amazing. It happened right after parents dropped their kids off, in a room devoted to PTA business. The room had musical instruments, whiteboards, stacks of books and markers, as well as pupil desks and the New York City flag.

But I don’t want to write about the meeting itself, interesting as it was. I want to write about something one of the parents asked me after the meeting ended and we were all chatting. She wanted to know what I thought about the school’s finances, this specific school’s budget.

I said I was writing a new series for my newsletter trying to understand NYC school finance, and that I hadn’t yet looked at it from the school’s point of view.

So this week, I wanted to do that: how can we understand NYC school finance from the school’s point of view—not property values, not the mayor’s office, not taxes, not the state or the School Construction Authority or the Transition Finance Authority or the bond market or even the Community Education Councils.

To riff on Husserl: to the schools themselves!

I started by digging around for numbers. How to see NYC school finance from a single school’s perspective? First we should consider some sources. At this point, I haven’t found any public troves of building-level budgets. Maybe I’ll find it soon. Rather, I’ve got a number of dashboards that helpfully report lots of numbers, but not all of them.

The first can be found from the school’s website in schools.nyc.gov. The IBO has a helpful set of videos about how to do this. I’ll use a school someone asked me about randomly the other day as an example, P.S. 263 Emma Lazarus in Brooklyn.

Before anything else, you better know the four character code for your school, which isn’t necessarily the same thing as its numbered name. In this case, PS 263 is known as K263 in the DOE system. So let’s dig in.

FSF

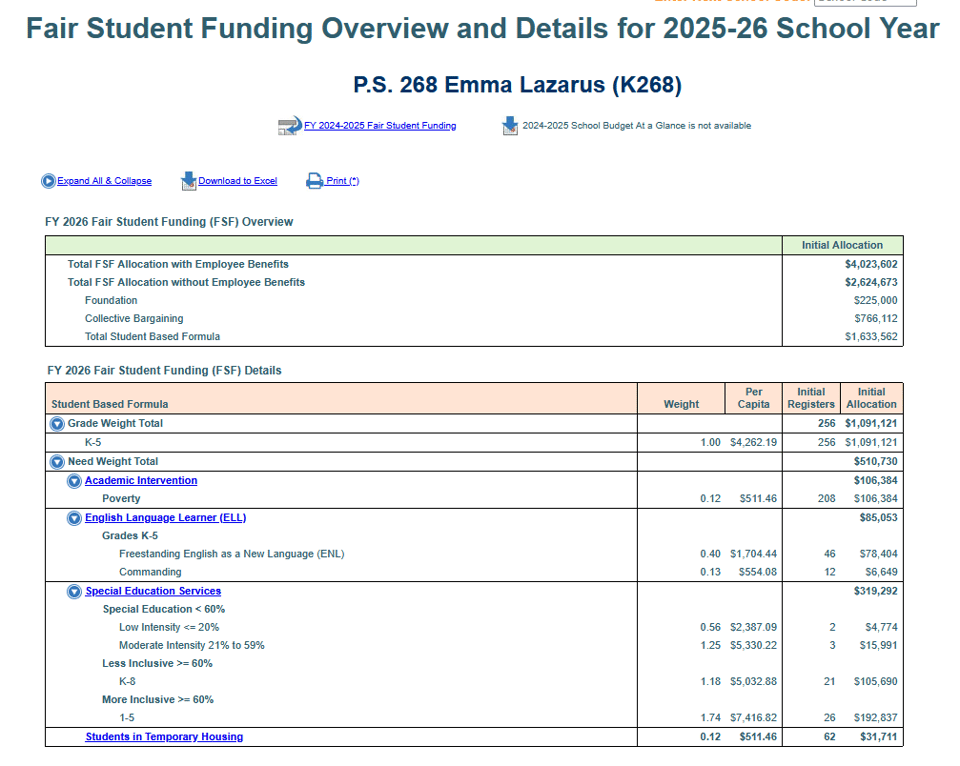

Here’s the school’s page in schools.nyc.gov. Under Reports, we can find a Budget and Finances tab with four options. First is the Fair Student Funding Detail tab, which provides a detailed breakdown of the school’s allocation by weights.

What the heck is all this? As the Independent Budget Office (IBO) explains,

The NYC Department of Education (DOE) created and implemented the FSF formula in the 2007-2008 school year (though it was not fully funded until the 2021-2022 school year). FSF is used to fund almost all traditional public schools.

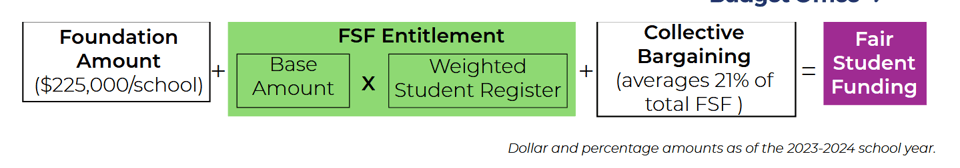

FSF has three major components:

• a fixed foundation amount of $225,000 per school, regardless of size, meant to cover core administrative staff

• a variable entitlement amount

• a variable collective bargaining (CB) amount that funds increases to staff salaries as negotiated by the City through collective bargaining

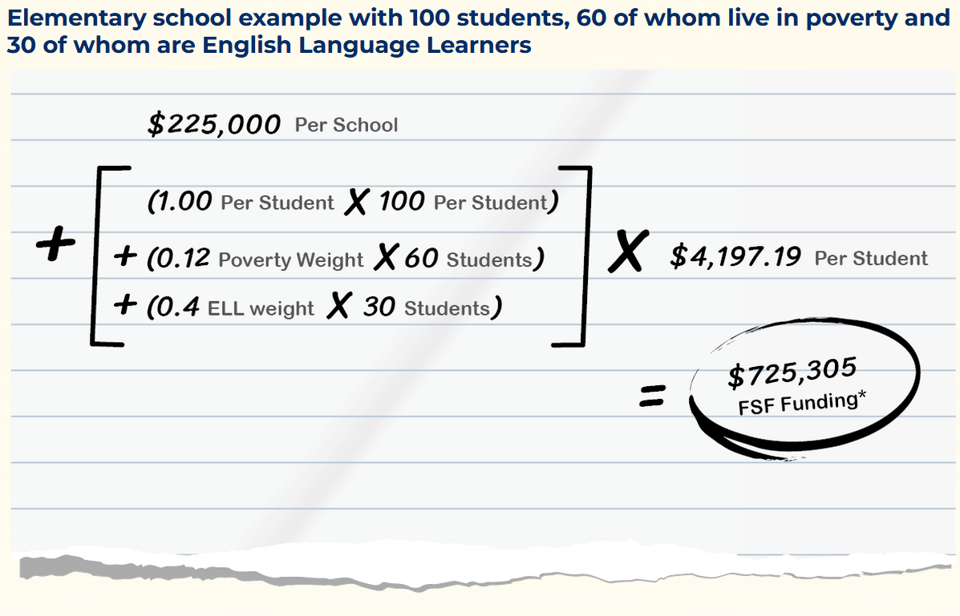

So above, you can see the foundation and bargaining amounts up top and the grade weights and need weights on the bottom. The total registered population is 256, which yields a certain amount for the grades taught as a primary school. Another way of representing it is the comptroller’s 2023 picture which, while some of the weights might be out of date, the overall picture is there:

At Lazarus, the need weights are broken down into poverty (208 students), English as a New Language (46 students, ENL), commanding (what is this? 12 students), special education services along a spectrum of more or less inclusive (51 students), and students in temporary housing (62 students).

After all that, the school gets about $4 million, which includes employee benefits. So there we have a basic picture of the FSF revenue.

Galaxy

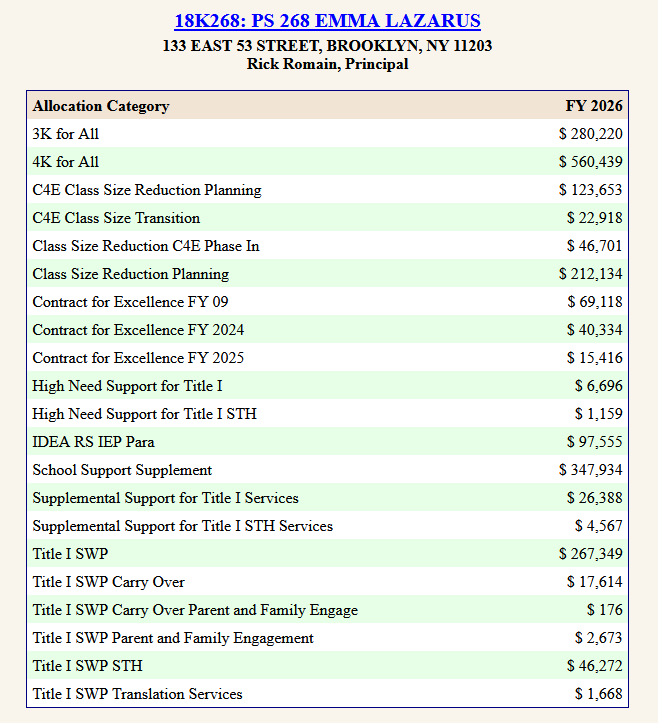

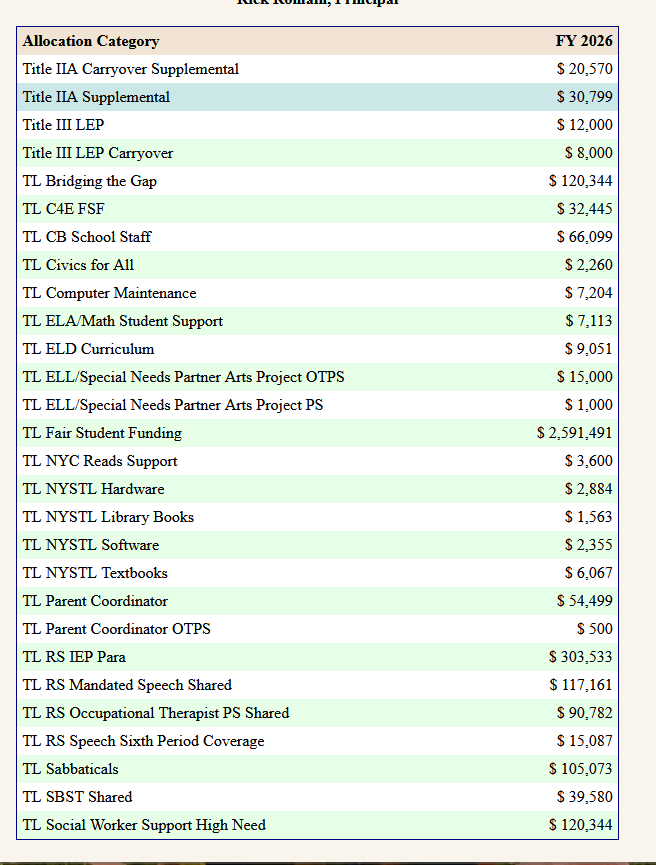

But there are more revenues that go to the school, and also breakdowns of where the revenue gets spent, under the Galaxy Allocation tab.

Here are the number breakdowns for the school’s allocation by specific subcategory. In the second panel you can see that the FSF is by far the largest allocation at $2.5 million. But there are fun specifics to look at.

As an interesting aside, I searched around for what TL means. The AIs built into search engines said it meant “teacher leader,” which made no sense. When I asked a human who knows, they said—and I verified—it means “tax levy,” which does make sense.

Everything with a Title (and IDEA) in front of it comes from federal sources, and you can see how important that money is for specific purposes. If it gets reduced, it’ll hurt.

Participatory?

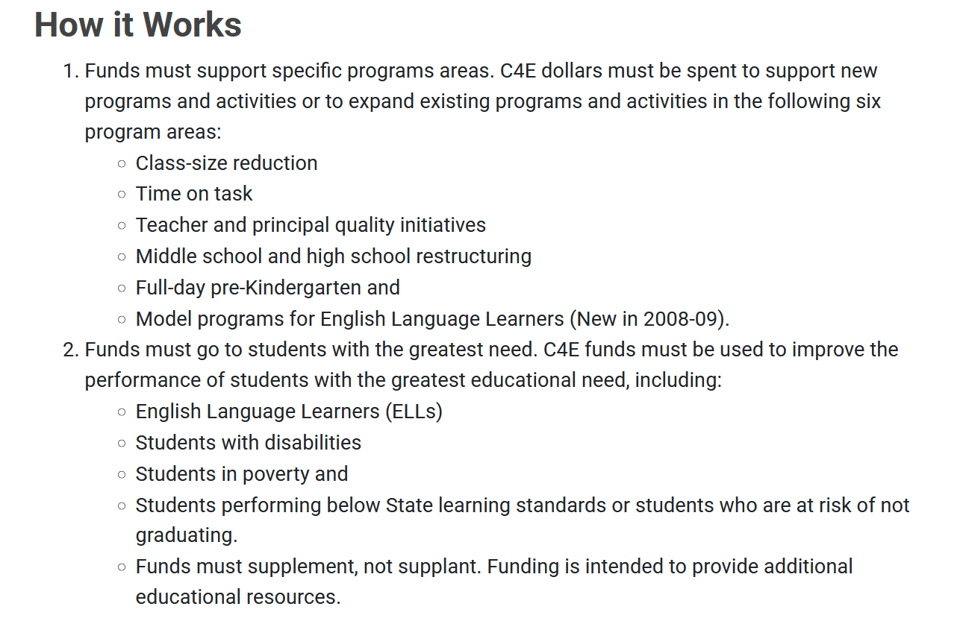

The Contract for Excellent (C4E) is another interesting aspect of school finance in NYC at the school level. From the DOE website:

The NYC Department of Education receives some of its annual budget from the NY State Foundation Aid program. Every year, the State allows some of the additional aid to be used for growth in general operating costs and investment in ongoing programs. However, some of the funding must be used according to the State’s “Contracts for Excellence” law. New York City schools received Contracts for Excellence (C4E) funds for the first time in the 2007–2008 school year. These funds under State law must be given to certain schools and must be spent by those schools in specific program areas.

According to the Ed Law Center:

Under the C4E law, the New York City Department of Education (NYC DOE) and New York school districts must develop a plan for allocating increases in state aid to resources and programs essential for a sound basic education as determined by the Court of Appeals in the landmark Campaign for Fiscal Equity (CFE) rulings. The districts’ C4E spending plan must then be vetted through a public process. In NYC, the process includes borough-wide hearings, as well as presentations at the 32 Community Education Councils (CEC) throughout the City.

So the CEC itself develops its C4E budget based on its needs, allotting certain monies for particular instances of growth. It’s like a district-specific contract that can allocate money for things the state foundation grant wouldn’t necessarily get to. Is it a semi-participatory form of budgeting from the district perspective? Maybe.

It was established after New York’s big school funding lawsuit called Campaign for Fiscal Equity v. New York. (A fun aside: at the PTA event I met a woman who was a plaintiff in this case when she was in high school!) This is a case I want to study more carefully.

The DOE lays out how C4Es work:

So you can see there’s a lot to parse. I found myself toggling back and forth between years to see the movement of these lines of funding. It’d be great to have a site like the dashboard that takes each line and sets it over time so you don’t have to do that (something to note).

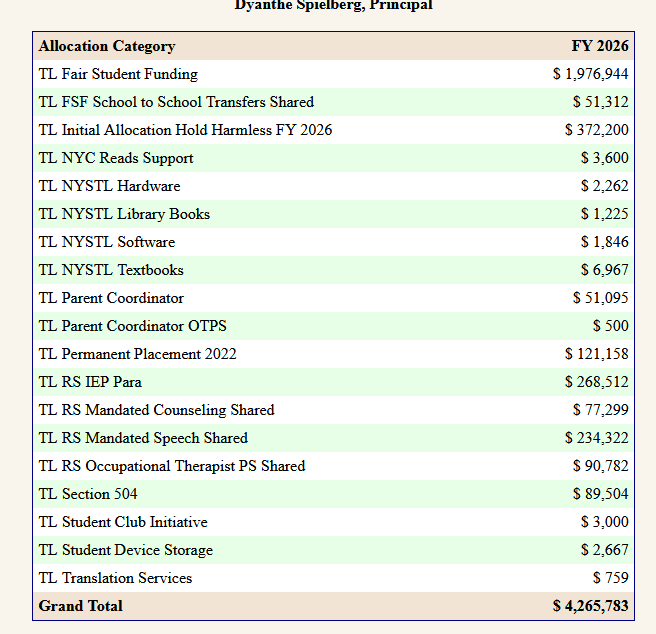

Held harmless

The last thing I wanted to look at wasn’t from Lazarus, but rather the Neighborhood School, another build I’d had a request to look at. It’s the tax levy line that says “initial allocation hold harmless”:

According to recent reporting in the Queens Chronicle, which is unusually perspicacious on this question, this payment is meant to keep schools whole despite decreases in their enrollments mid-year:

Schools with lower-than-projected enrollment will not have to give money back midyear, the city Department of Education announced Monday. The “hold harmless for the mid-year adjustment” decision will let them retain more than $250 million.

About 65 percent of schools will be held harmless this year, with the remainder slated to receive additional funding for greater enrollment than projected.

Chancellor Aviles-Ramos summarizes this issue with an official quote:

“We know that stable and robust school budgets are critical to giving our students the world-class education they deserve,” Schools Chancellor Melissa Aviles-Ramos said in a statement. “That’s why, as we navigate enrollment fluctuations and uncertainty around federal funding, we’re committed to providing stability and ensuring every school has the resources it needs. Continuing to hold schools harmless for the 2025–2026 school year will allow educators to focus on what matters most — helping our students thrive.”

When the FSF was implemented, according to the IBO, there were a couple phases, the first of which was this hold harmless policy: “The first provision, named hold-harmless, was devised to avoid sharp budget cuts in some schools.

These schools could maintain their previous year’s budget if their FSF allocations were lower than their prior budgets.”

That’s a good thing, because, as the Chronicle notes:

According to the DOE’s preliminary, unaudited figures for the 2025-26 school year as of Oct. 31, enrollment in K-12 and preschool fell by 2.4 percent. There are approximately 884,000 students enrolled in New York City public schools in the 2025-26 school year, down from 906,248 for the 2024-25 school year.

Hold harmless is something I want to look at further, particularly when I try to dig into the state foundation aid grant: I’ve spoken with others about how hold harmless might not be fair because certain schools who face enrollment cuts (like The Neighborhood School) might not need those funds held harmless as much, because other schools (like Emma Lazarus) might need those monies. Sure, TNS might’ve had enrollment drops, but it’s a well-resourced school—we haven’t even looked at PTA monies yet. Along with this dissertation looking at the equity of FSF, this would be a vector to examine: just like histories of structural benefit and privilege in racial capitalism aren’t equal, not all enrollment declines are equal.

So overall, when we go to the schools themselves, we see that their revenues come from the FSF mainly, but several other important sources that are smaller yet under threat, and have a legacy in the fight for funding equity in the state courts, like the Contracts for Excellence. We also see an interesting debate about hold harmless, which we should consider as enrollments decline.