The ideology of 322%

Call for participants! I'm helping put together a workshop on capital expenditure, debt, and K-12 education that will use critical frameworks to talk about policy and practice. We want to foreground perspectives from people on the ground in schools and districts and elected offices and unions, etc. I know a bunch of you out there fit this description. If you're interested in participating please respond to this email and I can tell you more!

*

Last week I wrote about the epistemological problem in teacher pension policy, which quickly becomes a political one. How can we know the truth about teacher pensions? It's not clear. Between equal numbers, force decides.

Like I did with Andrew G. Biggs, you have to look at where people get their numbers and how they calculate those numbers, seeing how people claim to know what they know about teacher pensions, and who benefits from this knowledge. The neoliberal economist Chad Aldeman, who I've mentioned before and has become a kind of oppositional touchstone for this pensions project, gets his data from an entirely different source than Biggs: the Equable Institute, specifically a report they did called "America's Hidden Education Funding Cuts."

In this report, Equable also makes the stunning claim that teacher retirement costs for employers (what employers spend on teacher retirement) has increased 322% since 2004. I mentioned this claim in a previous post but didn't get into it, so I think it's a good one to dig into as an example of this question of how we know what we know about teacher pensions. Let's look at Aldeman's use of the number, zoom in on this incredible claim about the retirement costs and Equable's report, then zoom out into what this all means for the politics of teacher pensions.

How to get to 322%

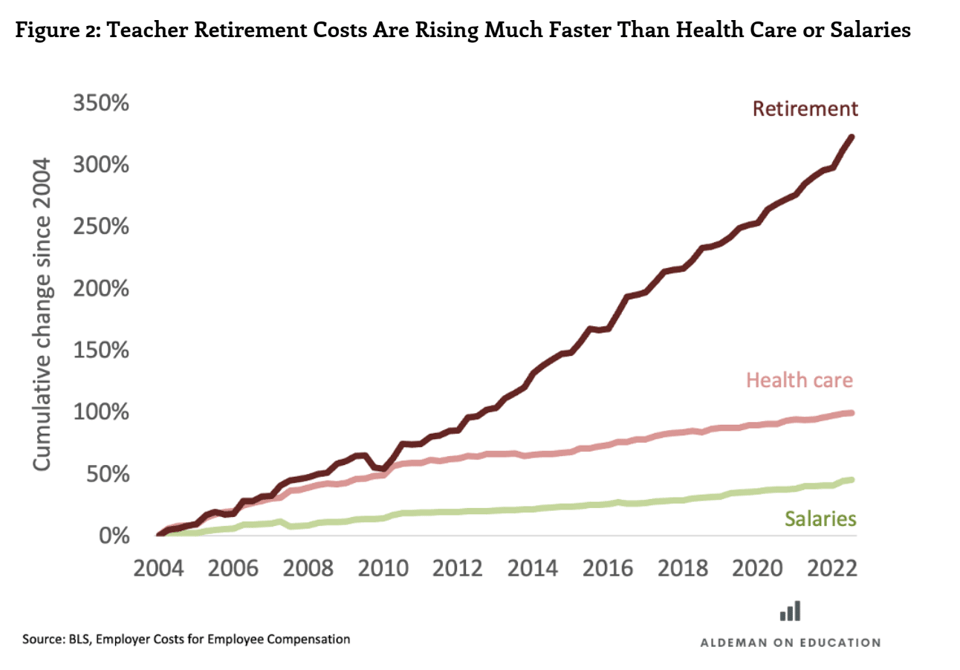

Aldeman makes the case that retirement costs are out of control. He shows how these costs to employers have outpaced healthcare and teacher salaries in a post called "Schools Pay More, Teachers Get Less."

That dark line is freaking off the charts. It's breath taking. You usually don't see serious people pushing numbers like this. But this number has gotten around. The school finance consultants at Allovue picked it up too in their report on pension debts. So I wanted to see how Aldeman got to this number.

He says these numbers come from the Bureau of Labor Statistics on employer costs on employee compensation at the bottom left of the graph. I tried to look these numbers up themselves but got lost, since a couple times each year has its own report and it's hard to tell which number he's using exactly.

From what I can tell, the BLS numbers are broken out by employer costs for teachers, kinds of teachers, and education service providers in industry. We can also see how much employers are paying for retirement and savings for state and local employees, broken out by teachers. But there are several numbers here.

For example, I can see a Teachers category that includes "postsecondary teachers; primary, secondary, and special education teachers; and other teachers and instructors." Employers spend 12% of these folks' compensation on their retirement and savings.

But then there's a category for primary and secondary teachers and the number is 14%. But that's an Occupational group. There's also an Industry group which includes Education Services (7.1%), breaking that out further into elementary and secondary schools (11.8%) and postsecondary schools (13.6%). So which number is it that's increased 322% since 2004? If you averaged all these you'd get a different trend than if you chose one of them in particular; and even the average has multiple interpretations, if you chose the median rather than the mean average or mode average you might get something else. Should you even average them? Maybe Aldeman and Equable add them together somehow and use that amount?

Adding them together would be a scandal. Averaging them hides a lot. For instance, when you say "districts are spending X on teacher retirement" can you really include postsecondary educational services in that number? No. So which do you pick? I don't have the time or inclination to try and recreate all the trends in these numbers going back to 2004, maybe someone else does, but I imagine there's a specific path to 322%, whereas other paths have smaller numbers.

(As an aside, I can see from this June 2023 BLS report that employers of state and local workers spent 13% of those workers' compensation on defined benefit retirement plans, whereas they spent an astoundingly low .9% on defined contribution plans. You can see the anti-solidarity in those numbers: the employers taking on the responsibility for the social risk of teachers aging in the big number, the employers abdicating that responsibility to the market in the small number. I digress.)

Equa-what?

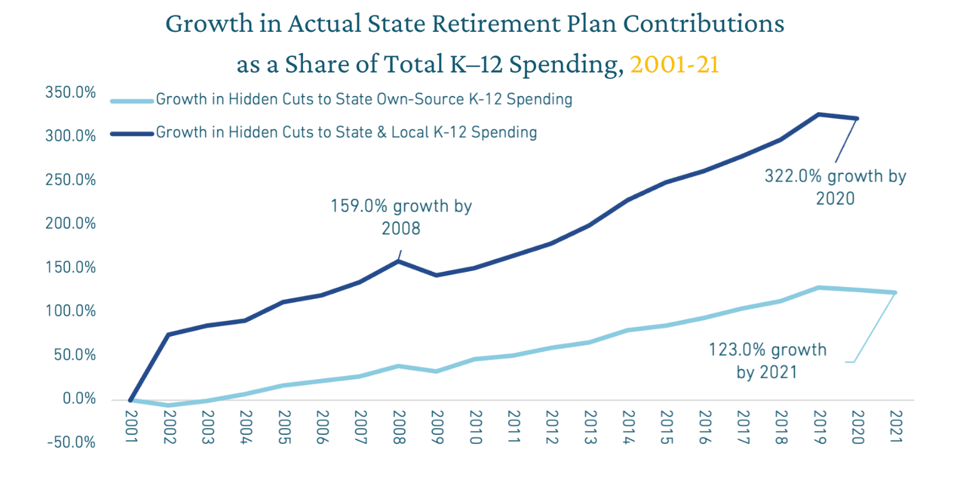

But Aldeman also says in the post that he gets his numbers from Equable's report, where we find a similar graph with the 322% number. They give a little more background on this number though, rather than merely casting it as 'retirement costs' plain and simple, by saying that it's "state and local K-12 spending." Again the state/local distinction rears its head.

So Equable makes clear that it's K-12 spending at both the state and district level as measured in terms of "actual state retirement plan contributions as a share of total K-12 spending." But this gets me asking questions too. What does percent growth of retirement cost as a share of total K-12 spending really mean? Does that mean we're calculating the difference in contributions to retirement plans from year to year vs. the difference in total K-12 spending year to year? Like, if in year X retirement cost was 1% of total spending, and the next year it was 1.2%, then the growth was 20%.

And when it comes to 'total K-12 funding', is that total K-12 spending per state? Per district? Federally? And is "actual state retirement plan contribution" different than normal cost, and how is that related to the different discount rates that pension policies use to calculate the contribution rates (see below)? And why is the 322% number a combined number of "state and local" contributions, while the graph itself is titled "actual state retirement plan contributions"? Wouldn't it be actual state and local plan contributions?

Below their graph, they say:

The dark blue line shows the growth in share of state and local spending going to teacher retirement costs since 2001. The majority of funding for schools comes from the local level. From this perspective, looking at hidden funding cuts in the context of combined state and local spending provides a more complete understanding of the impact of these hidden education funding cuts.

This is a little fishy, since states actually provide the majority of K-12 funding, edging out the local level by a few percentage points. If the state share of retirement contribution increase is 123% and the state and local share increase is 322%, where's the extra 200% coming from? Where's the line breaking out local contributions? And are those local contributions using state money? I feel like they're adding things up that are already included in one another, or don't necessary go together.

Cui prodest

They say "Data collected for this report came from a wide range of sources, including the Census Bureau, state and local retirement systems, and the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO)." Like Biggs, they say that "Both the NASBO and Census data have strengths and weaknesses which are summarized in this report and detailed in the complete methodology." They have a Methods section as well (Appendix B of the report), which actually links to a longer Methods overview in an entirely separate document. It's a long document that I'll have to save for another post, as well as a reconstruction of their path to 322%; needless to say, they admit their numbers are limited.

For now, I looked up Equable in ProPublica's Nonprofit tracker. According to their 2021 tax forms, they got the majority of their revenue ($806,418) from private sources, only receiving about $80,000 from government grants. Since 2018 they've gotten about $8 million total--their donations are hurting! They call themselves bipartisan, which reads neoliberal to me. They don't list a board. They don't disclose donors. They were founded in 2018. The people on their staff are all researchers and former state officials. Compare that to the the PPD from last week, which has been around for decades and works more from professional actuarial data.

The ideology of the question

At first, I wondered why Aldeman would get his numbers from Equable and the BLS rather than the PPD, where Biggs gets his data. I thought maybe it was an ideological thing, but then it seemed like it's more a research question thing. Aldeman is interested in showing that districts are spending way too much on defined benefit retirement plans, so he looks at employer expenditures data. Biggs is curious about whether teacher pensions are solvent, whether they can meet their obligations generally speaking. So the datasets answer different questions.

But I realized this is no less ideological. Althusser has a line somewhere about how we have to ask questions about the questions we ask. It seems to me that the more solidaristic question is Biggs's: to what extent can and will teacher pensions, using defined benefit structures, meet their obligations? Will the pensions run out of money? He actually says in his article that, while it can vary from pension to pension, they'll all be fine and their reserves could hold them steady for a decade even in the worst of circumstances!

That's an analysis of whether the solidaristic policy we have in place is healthy. Aldeman's question is more market-oriented: to what extent are school districts taking money away from students and teachers by having to pay pension costs? The question about retirement costs is ideologically configured to undermine the stability of the defined benefit, while the question about solvency is ideologically configured to assess the stability of it. (You could also construe this question as asking about the extent of the solidarity the existing regime can provide when the risk is distributed to districts rather than, say, the federal government.)

Notably, in the beginning of Biggs's article, he says that state and local contributions to retirement and savings between 1998 and 2018 only increased .9%. He doesn't break that out into teacher retirement plans, but he's using his PPD dataset to talk about the increase in cost.

It's hard to square the Aldeman/Equable 322% figure with Biggs's number. How could the average state and local contribution to retirement across occupations and industries be .9% while when it comes to teacher retirement costs it's 322%? It doesn't add up to me.

If teacher retirement costs really rose that much, wouldn't that .9% figure be much bigger, given that teachers make up one of the biggest populations of state and local employees in the country? Equable says it's because of pension debt too, but is pension debt even a real problem if the pensions are solvent? Equable and Aldeman are saying this might be true for districts and states as they make their contributions, and certainly I've seen high pension contributions at the district level. (This gets us to the question of whether there's really a pension crisis, which I'll talk about in another.)

But therein lies the ideology: do you look at things from the perspective of the district and state, or do you look at them from the perspective of the pension? Asking about your own question reveals your ideological position and the kinds of numbers you might produce. Given that the cost of DC plans is ten times less expensive than the DB plans according to the BLS, if you're ideological project is to reduce government spending no matter what, and move things into the market, then 322% makes sense.