The horizon of discount rate politics (part 2)

Quick link: I published a piece in The Baffler about socialist mayors and the muni bond market, check it out.

For this week: This is the second part of a presentation I gave to the K12 Critical Budget Institute. The first part is here.

***

Yesterday, you might remember that I spent a little time talking about politicizing the discount rate. I just wanted to bring it up and explain it a little bit more, and I wanted to see what you thought about it.

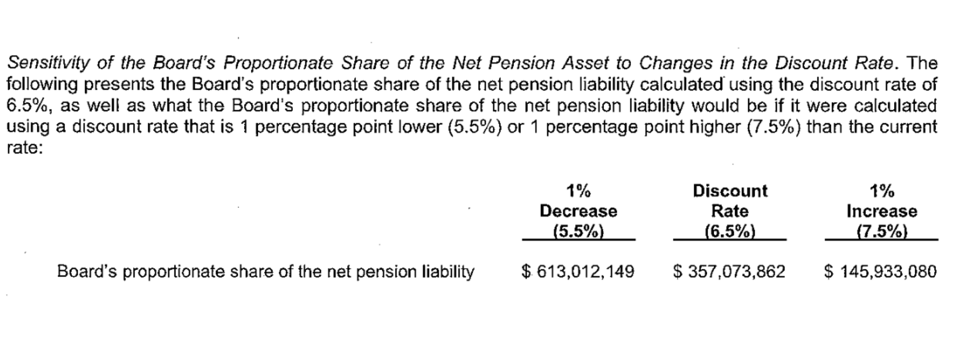

In every CAFR, and when I say CAFR, I mean certified audited financial report, there's a little section called “the Sensitivity of the Board's Proportionate Share to the Net Pension Asset to changes in the discount rate.” The discount rate is the time value of money. There's a new book called Discounting the Future, which is one of the best books I read last year. It really blew my mind. If you want to understand what financialization is, both materially and historically, this book is about financialization as a way of thinking about what we value in terms of what it's going to be worth in the future, and how we then think about that now—net present value.

So, let's take a pension fund. If I think my pension fund is going to have, you know, really great returns in the next 30 years, I'm going to set a high discount rate because I think that it's going to have a lot of returns. The time value of money is high. It's going to be making money on the market over time. But if I don't think my pension fund is going to be making that much money, I'm gonna set a low discount rate. Low discount rate means that this pension fund's not going to be worth a whole lot in the future.

Now, why is that important? Because when your school districts and states are contributing to the teacher pensions and other pensions in the municipality, the way they calculate the magnitude, the size of that contribution is with the discount rate. And the size of those contributions from year to year vary dramatically, depending on what they think that pension fund's gonna be worth, what they think they're gonna get from the market.

If they think that they're gonna make a good return, the contributions that the district has to make into the retirement fund are going to be lower, on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars.

But if they think that there aren't going to be good returns, for whatever reason, and they lower the discount rate, those contributions are going to increase. And that's going to put a strain on the budget at the state level and the district level. And the thing that this book Discounting the Future does so well is it says that the discount rate is a political technology. It is a calculative device that creates worlds. It creates and destroys worlds. And right now, for movements and unions, the discount rate is just like, what the hell is that? An esoteric public financial thing that's buried in the back of these documents.

But that esoteric what- the- hell- is- that financial thing determines, on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars, how much a district and a state are going to contribute to a retirement fund. That could determine whether or not 300 people get fired in a year. It could determine whether or not 20 schools close. It could determine whether or not you're able to offer special education programs and specialists, it could determine the busing, the nutrition, all the elements of the budget that are going to hurt more if you have to put more into the pension, which obviously have been underfunded structurally, particularly since 2008.

Question: I want to make sure you're accounting for other factors here. Because this discount rate isn't a fixed thing. It's based on market conditions, right?

So if you measure the rate of return, that fluctuates, but the discount rate is what we design. What we think is going to be true in the future. But this is a good question: what do we control, and what are we just passively measuring? It seems like the discount rate is just some cold inflexible number we don’t have power over, that it’s just a measurement of returns. But that’s not so. There’s a political question here: someone sets that discount rate, someone decides. So who’s it gonna be? Is it just the pension managers who get Wall Street consultants for hundreds of thousands of dollars to tell us what they think the discount rate should be, or is it gonna be all of us together to figure out what the discount rate should be?

I think it should be all of us together, as a community impacted by the decision to set the discount rate high or low. But right now, the are the pension managers and the consultants they hire, telling them whether Winston-Salem schools, in this case, should have a 5.5%, not a 7.5%. That two point difference in the discount rate is worth more than $500 million in pension contributions. It's the difference between $613 million, as opposed to $145 million.

Question: When are decisions made every year?

Every pension will have a different cycle of decision-making, and I think sometimes it is a yearly cycle, but others it’s every few years.

Question: Right, I just wonder how significant a decision this is, considering there's a normal cost of pensions, states are paying into it in a way that’s related to the school funding formula, et cetera. Like, after a year, what the rate actually is, they just measure it, because the returns have come in or not. I don't know what the delta is. It seems like it's a year to year delta, not long- term. Basically: is there really a there there in politicizing the discount rate?

Well, I mean, if, for instance, over a period of three or four years, you were to structurally decide, I'm talking a quarter of a point, 25 basis points, 0.25%, a small increase in the discount rate, over a period of three years, if people like unions and movements were more involved in that discussion, that could save schools districts $100 million on the budget, because when you set the discount rate, it's a speculation about the future, not just a naturally occurring thing from the past. I think that's what you're asking, right?

Question: Yeah, I'm a little skeptical, but I'll keeping listening!

No, that's fine. Yes, because this is a horizon, and it’s why I’m bringing this to you today—to see what you all make of this. I told you this story yesterday: after I appeared on a podcast, the then head of the Chicago Public Schools emailed me and was like, “oh, I heard you on Have You Heard, what do you think's going on in Chicago?" And I looked at it, and I was like, "Well, the discount rate on this MEABF pension is sort of giving you problems. Why don’t you fuss with the discount rate a little and then you could save $100 million. He was like, “well, I don't know about that!”

But the reason he said that he didn't know about it, that he wasn't sure about the strategy, was because, well, we don't want to be seen as fiscally irresponsible. And I want to address that now, because I heard your skepticism in your question before.

Because if you say, “let's increase the discount rate,” what you're saying is, “oh, we're going to make great returns. We don't need to pay into that pension as much now. We're not going to owe ourselves anything in the future. We don't need to save right now, we can spend right now.” That's the calculation. So what fiscal conservatives and moderates and centrists are going to tell you is that you're irresponsible because you're not saving for the future.

But that's a debate we can have. We can have that debate. We can say, “actually, given market conditions, the returns have actually been pretty good. Given our needs right now, it is rational and reasonable for us to say: ‘we need to spend right now, and then we'll figure out how to save later for our retirees’.” Now, that might be a wrong decision. I'm not saying that you need to do it either way, high or low on the discount rate, but I'm saying that that should be a decision the people make, not just the ruling class, which is how it's done currently. And that's what I mean when I say politicize the discount rate, I don't mean necessarily always be demanding that the the discount rate go higher. I'm not saying that at all. I'm just saying that we should treat the discount rate like a calculative device that creates and destroys worlds, and that has an impact on our lives and our budgets every year.

Question: There's a relationship with the time frame here, right? It's like the state, they just keep pushing out the fully funded year for the pension, which, in some ways, we hate because they're basically saying, like, ”oh, we'll just keep moving the data and it moves forever.” On the other hand, it's good for right now, because it prevents them, it allows the state to say, “we can still spend more money over here rather than put it in the pension, because we don't have to put in more to the fund because there's a longer time frame for full funding. So that must be related, right?”

Yes. Of course, because once you get into the pension stuff, there's unfunded liability and the state covers it to a certain extent and there are thresholds, you know, but when it comes to the state budget every year, this stuff matters for the school districts, because it determines how much money can go to the school districts for tutoring or whatever, or has to go into the pension fund. And I think if movements were smarter and could participate in that conversation, it would garner at least a certain respect to be able to have a dialogue about it, rather than just letting them take care of it.

Question: Can districts negotiate the rates?

That's a good question. I don't know if individual districts can because depending on the district's relationship to the pension, it could be that the pension operates at the state level, and it does its retirement services for the whole state, or a district has its own pension, in which case, in some places, a district does have more influence, like Chicago, for instance, they have more influence than places I've heard, but in other places like we were just talking about, you know, like Maryland, all the districts in Maryland have to pay into the state pension. And so the ways in which districts could have influence over that, it's different.

But I think, like, in the Maryland case, if the unions from all those districts got together and said, "Hey, we want to write a letter”—I know we don't want more words on a page and to just be resolutionaries and everything— but if there was a letter that said, "Hey, we want to participate in the decision about the discount rate for that pension,” that would raise some eyebrows, you know, in a way that I think would be helpful.

So when you're looking at your documents, control F discount rates, you see what comes up— as I'll say later, you control+F and find out.

Announcement: After working with the press on the promotion of my new book As Public as Possible, they gave me a discount code for readers of this newsletter.

If you pre-order the book now, you can use the code TNP30 to get a discount.

Meanwhile, I’ve got some book event dates set up. Here are the dates and places so far:

12/2/25 @ 2pm - Seton Hall University, South Orange, New Jersey

12/3/25 @ 7pm - HUUB, Orange, New Jersey, with teacher-organizers,

12/10/25 @ 6:30pm - Skylight Room, CUNY Grad Center, New York City, co-release with Celine Su

1/12/26 @ 2pm - School for Advanced Studies in Social Sciences (EHESS), Paris, France, with Nora Nafaa

2/9/26 @ 8pm EST - Debt Collective Jubilee School, online

If you want me to come do a talk, either online or in person, with your group/office/chapter/whatever, I’m happy to set it up. Just respond to this email. More dates to come!