The biggest threat to pubic education you didn't know about

There’s been a kind of firestorm in public finance over the last week. From the federal funding freeze to its confusing (non)recission to Elon Musk’s Department of Governmental Efficiency’s raid on the Treasury’s payment system, we’ve seen the federal government’s financial plumbing be challenged in transformative, and maybe revolutionary, ways.

Nathan Tankus is sounding the alarm, saying things aren’t good, and I trust his instincts. He’s said “they’re doing the Reichstag fire to the most crucil and foundational layers of the federal payment system,” for instance. Read his very helpful breakdown of impoundment laws and his post just this morning about Musk’s incursion into the payment systems for this purpose.

So does this affect public education?

Sociologist Beth Popp Berman had a good thread break down the situation and applying it to school finance. It’s helpful but also she misses something important. She writes:

how do you coerce the submission of locally controlled school districts around the country when you: - Only provide 8% of their funds, and they’re - Mostly distributed by formula based on population and number of low-income students?

You’d like to say, “We will not distribute Title I funds to schools until they demonstrate their curriculum is ideologically and politically compliant.” But there’s no simple mechanism for actually carrying that out.

But if you take control of the federal spigot —what was previously apolitical plumbing—you can do just that. You don’t need to move a whole bureaucracy or deal with lawyers. Elon and his team just turn it off. Law doesn’t play into it at all.

And schools are just one example. Want to end resistance from blue states who won’t facilitate sending immigrants to Guantanamo? We’re turning off Social Security payments to your residents until your police start to comply with ICE.

This is a good analysis and it’s gotten a lot of attention because it focuses us on the power of the “federal spigot,” in the context of US decentralization at the local, state, and federal levels, which, in a case like the present, is generally a good thing—except, as Berman notes, when the federal government makes changes to the spigots that control resources through the whole network.

I wanted to take issue with Berman’s claim that what the federal government can do to coerce local school districts is threaten to stop social security payments. I don’t think that’s right.

The real threat lurks in documents swirling around a process that hasn’t been in the headlines the last two weeks: reconciliation.

Pendulum

Since Republicans have a trifecta at the federal level and they’ve captured the court system, they can pass legislation. It’s their window to make some big policy changes.

The last time such a window opened, the Biden administration did it’s sort of extraordinary infrastructure program in the form of the infrastructure bills (BIF and IRA), CHIPS and the like.

If those programs were informed by heterodox economic thinking—a triumph, albeit muted and diluted, for a political economy and public finance that doesn’t reserve government extravagance for the ruling class—the Trump administration and its trifecta will go in the opposite direction. The pendulum is about to swing the other way, towards ulta-orthodox capitalist thinking—and pretty intensely.

I’ve looked at some of their proposed education policy from Project 2025, focusing on shifting categorical grants to block grants, then zeroing out federal grants for education, and reassigning Education Department functions to other departments, enacting a radical states’ rights program.

While all that stuff’s a threat (I’m writing next week about the K-12 indoctrination stuff), there’s one threat you probably haven’t heard of that might be more powerful and could do what Berman imagines.

Exemption

The Ways and Means Committee put together a big list of dream policies for the budget reconciliation process that’s coming up over the next year. That process will be how the Trump administration and its trifecta passes its big priorities: reconciling a budget with existing legislative requirements, being able to pass that budget with a simple majority in the Senate, getting around the filibuster.

This reconciliation process—a workaround created in the 1970s—is how administrations have gotten big things done for decades, whether it’s Obamacare, Trumps’ 2017 tax cuts, or Biden’s infrastructure plans. It’s all in reconciliation. When you hear reconciliation, think “they have to put their budget together so they follow the laws that have been passed before.”

The list coming out from Ways and Means is a view into right wingers’ dreams. The word I keep seeing in it is “eliminate,” and I’ve been focusing specifically on the tax expenditure policies they want to get rid of.

Tax expenditure policies give breaks (through exemptions and deductions) from taxation and, in a backwards way, the stuff that receives these breaks are getting a kind of federal support because the federal government has said it won’t tax them. Tax expenditure is like when a bully says “okay, you can keep your lunch money this week,” and then tries to tell you that he’s giving you money.

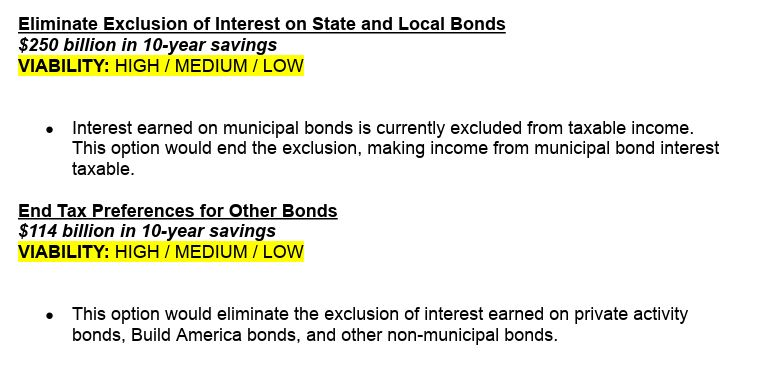

The right wing wants to ramp up the bullying: credit unions won’t get tax deductions or exemptions, hospitals won’t get exemptions, and, what really raised my eyebrows, interest on state and local government bonds won’t get exemptions from federal taxes anymore, along with other bonds that finance public projects like private activity bonds, Build America Bonds, etc.

I mean, wow. This would be a sea change, reversing about 110 years of public finance policy in the United States. The country’s approach has basically been to make certain kinds of bonds tax exempt, incentivizing investment in those bonds. The federal government has said: we won’t tax the interest you make if you invest in municipal bonds, thus compelling people to put their money into school bonds, for instance, financing school budgets for capital and operating expenditures.

But if interest on municipal bonds was no longer tax exempt, why would investors put their money into them? And how would pubic school districts get their liquidity between budget cycles and for capital programs?

The answer is probably: nowhere. It’d destroy the existing channels of financing for public education, drying up the revenue spigots to public school districts. It’s an attack on the largely invisible plumbing that gets public entities their resources.

Reconciliation is a negotiation process. The last reconciliation process featured lively debate, featuring big proposals that were eventually winnowed down, changed, and sculpted according to the legislative-representative-dialogical-dialectical back and forth of interests competing for influence.

For instance, there was a proposal for a National Investment Authority in the last reconciliation process. Jamaal Bowman tried to get the Green New Deal for Schools into the Biden administration’s budget, and the progressive caucus fought for the Build Back Better legislation.

At one point, these things were on the table. But they got taken off the table for various reasons, largely having to do with the relative strength of progressive and leftwing tendencies. They didn’t get those programs because their claim on hegemony was somewhat weak (although, I should say, it was the strongest I’d seen in my lifetime, which gave me a lot of hope for the new political economy of public finance).

This is all to say: the memo I linked to contains a wish list. It’s not policy yet, far from it. The stuff about tax exemption on municipal bond interest could get axed if and when the municipal bond industry and its lobbyists come out in force and say “um, no, you can’t do that.” I’d be willing to bet that they’ll flex their power and get those clauses removed. The municipal bond industry is a pretty powerful constituency.

But still, they’ll have to work for it! It shows the ideological chutzpah of the current rightwing bloc: they’re willing to put this shit out there and see what sticks. I feel bad for all the tendencies that don’t have similar power: credit unions, hospitals, etc.

My last thought on this might be controversial. Socialists could come out in favor of the removal of tax exemption for local and state governments, on accelerationist grounds. The strategy here would be to clear out this policy and make room for an even more generous, diverse working class finance policy that, when they get to power, they can put in place.

That’s a big risk and probably not worth it, but it’s there as an option! Tax exemption for interest on municipal bonds is one of the biggest obstacles in the way of a truly public education finance system in the United States.