Space and debt capacity near Cape Fear

Another tiktok request, this time in New Hanover County School District (NHCSD), near the Cape Fear River, around Wilmington, North Carolina. The request I got was to look into the district’s situation, specifically, I was told that “they tried to close a special ed school only to reopen as a refugee school and the board didn’t know. Now saying they will lay off a huge percentage of staff.”

What’s happening here?

This is a diverse district that’s suburb-ish, and mid-sized with 24,841 students. According to New America’s educational segregation map, this district enrolls 41.19% students of color and 58.8% white students. It has a poverty rate of 11.31% and a median home value of $277,900.00. Generally, it’s interesting to note that NHCSD gets 60% of its funding from the state, 30% from local sources.

The “special ed school” mentioned by the commenter is called Career Readiness Academy at Mosley. It’s a special program that serves about 63 students and has its own staff. They’ve got their own building, which also houses a pre-K and a special education program. The dispute is about closing CRA-Mosley though, and that facility—the building itself—becomes very important later.

Conversations about closing Mosley had been going on since 2021, apparently. The closure would have required moving those 63 students, who are identified as being diverse working class (largely Latino, 58% poverty). The proposal for Mosley’s closure inspired protest from those families. This protest was came made amidst two larger forces that have made this situation more intense: rightwing anti-immigrant politics and the federal pandemic relief fiscal cliff.

These streams are also flowing in a riverbed of the racial capitalist school funding regime, specifically the debt regime, which I think is an under-appreciated part of the story. So to get a sense of this situation, and some of the structural features surrounding it, I listened to a budget meeting held on Wednesday morning, Jan. 17th, 2024.

Space capacity <> debt capacity

The school district and county met that night to hear a presentation of results from a utilization study forecast. They hired a consultant (Matthew Cropper) to figure out how full are the school buildings in relationship to current enrollment and future forecasts.

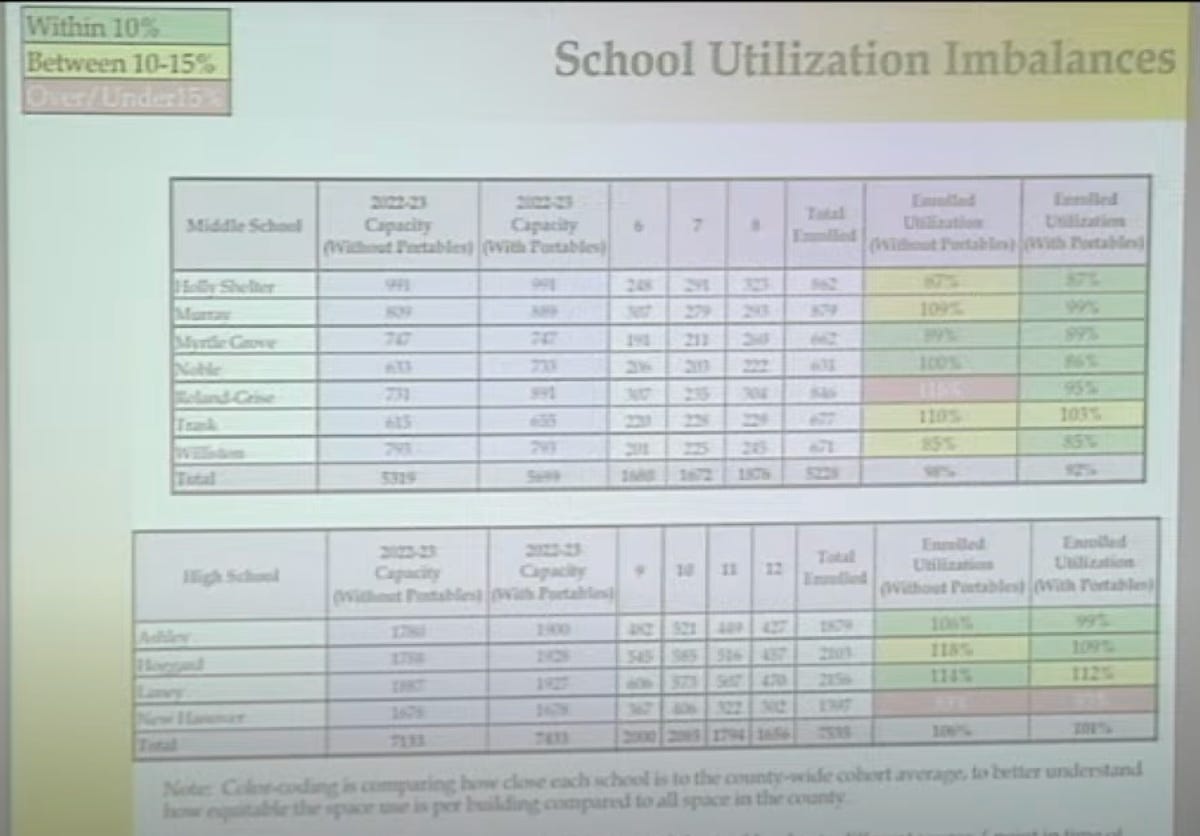

The consultant reported that there’s “extensive over-crowding,” such as in the slide below, tracking space utilization in middle and high schools. The red means that there’s too many kids for too few/small buildings. In general, Cropper found that the district’s facilities are 104% utilized, leaving no excess space in the county. Things should look light green/light pink, coming in somewhere between 76 - 95%. Instead, things are dark green (under-utilized, not enough students) and dark red (over-utilized, too many students).

Cropper emphasized that the district needs to add space for the kids that are here, and that there’s “no way to redistrict your way out of this.” The district needs to figure its space issues, and quickly. What does this have to do with closing Mosley? It comes up at a key moment late in the meeting.

At 1:33:02, after discussing the extensive space needs, a county board member, who sounds like the budget and/or finance director, says that the county still has about “$111 million in school debt that we have to pay down.”

This came up during a discussion about debt capacity, which is essential for financing the creation of more space for students to solve the utilization problem. Remember that school districts need to sell bonds, going into punitive and unstable debt, to get money for their infrastructure. The finance guy says the district sold a bond for $160 million in 2014, and ten years later, there’s still $111 million of that to pay down.

The finance expert then says he’d “caution the board to reserve debt capacity for things beyond schools,” since the county has to pay for police and other municipal services.

There’s a discussion about the structure of the debt, the fact that the 2014 bond was issued in $20 million increments over the ten years, refinanced several times, a kind of frustrated re-emphasis on the fact that this $111 million is all school debt, not general county debt from the above expenditures, and a hefty pause to appreciate the immensity of that amount.

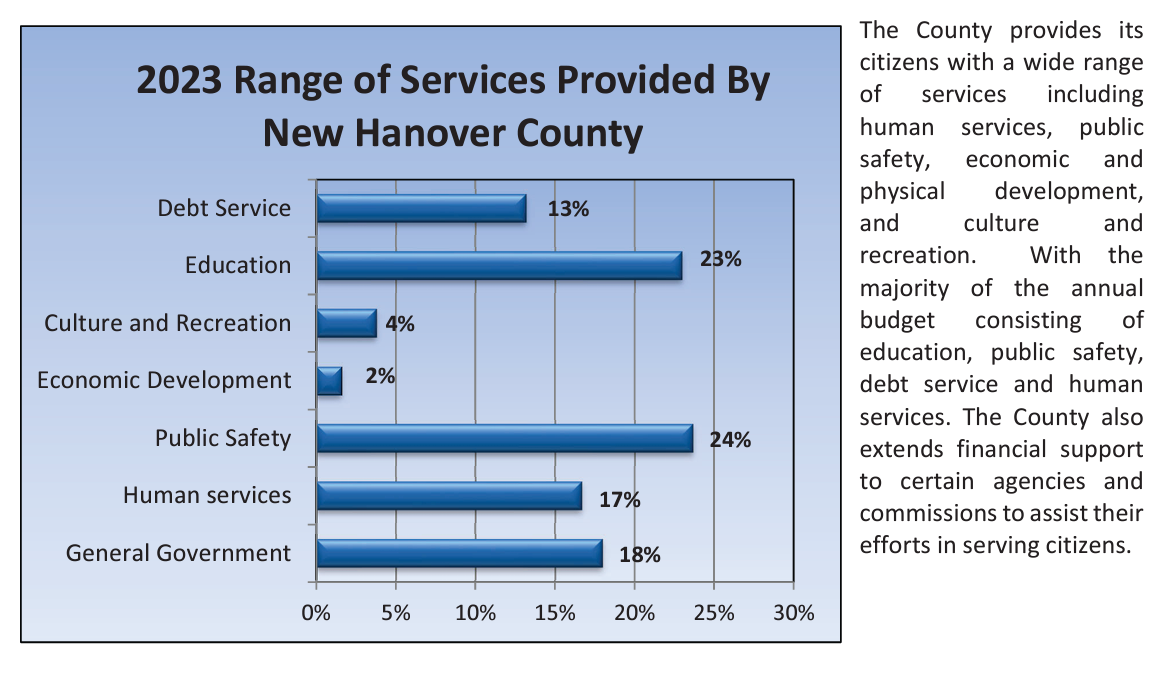

What the school board and county commissioners are feeling is that, while there’s a need for space capacity, there’s no debt capacity to create it. Debt service is already 13% of the percent of the county budget, behind education (23%) and police (24%).

That’s when Dane Scalise, a white male county commissioner, asks whether they’re getting ready to end the meeting, because he’s got something he wants to bring up. He says, “I want to follow up, because it pertains to a lot of what we’re talking about today, which is what’s going to happen with Mosley.”

Mosley money Mosley problems

Sitting across from Scalise is Charles Foust, the district’s Black superintendent. Among a few other comments, Foust says that “[o]ur thought would be to have a newcomer school there.” For context, the idea of reopening Mosley as a “newcomer facility,” is to make it a school that would serve new immigrants to help them integrate and get settled into the community. There’s a need for this kind of program, given that, according to the board: Vice Chair Pat Bradford has said there’s a “rapidly growing NHCS multilingual student population challenges - 1,505 new students over 4 years who are not English speaking, more than 35% this last year, is a serious challenge that must absolutely be addressed.”

Back to the January meeting. After Foust brought up the newcomer facility, there’s a heated retort from Scalise, who says that he’s concerned that having a newcomer school would attract more migrants and refugees “into our community.”

The tension is palpable.

The next notable moment is that a board member mentions that they need to present a budget to the county commission that cuts $11 million, and Mosley was one item where they thought they could save: apparently, it takes $1.3 million to run the school for 62 kids. Foust elaborates his rationale for cutting Mosley in this situation.

“It’s gonna be a hard cut this year,” he says, and I’m looking for return on investment.” Foust argues that given its poor performance on career readiness, the cost of running the program, and district’s need for that facility, that it should be closed. “Is it producing what it’s supposed to do? It’s not been doing that for years.”

And yeah, the budget situation with the district isn’t good. A month later, in late February, there was a budget work session, and it came out that there’s a $20 million shortfall going along with this situation, which reporting attributes to ESSER funds running out and the district’s reliance on those funds for hiring. About $11 million was put into staff.

A major cause of the district’s financial woes is that ESSER funding is expiring in September, about three months into the next fiscal year. A total of roughly $40 million that was part of this year’s budget is running dry; a little over a quarter of that, $10.8 million, was tied up in recurring funding for staff — meaning the district now needs to find a new funding source, or make cuts.

The district’s communication director had an interesting take, which is that the district was trying to absorb the ESSER hires into non-federally funded streams, but there weren’t enough retirements and attrition to do so.

Knowing that funding was ending and as phases of ESSER have completed, we had already started transitioning people from ESSER positions into locally-funded positions. However, the rate of retirements and attrition has been much lower than expected and there aren't enough vacancies to absorb all of the positions.

Ultimately, the shortfall required the schools to ask for money from the county that they didn’t get. “Despite asking the county for $10.1 million, commissioners allocated $9.2 million.” So that’s why you have cuts.

In the end, Foust lost the argument. Mosley is going to remain open, there’ll be no newcomer school, and the superintendent Foust was fired in early July for reasons that the board won’t reveal. (Incidentally, they have to pay him his remaining wages and benefits, which comes out to more than $250,000.)

The riverbed

I keep thinking about that moment in the January meeting where the school board and county commissioners reckon with the fact that there’s still $111 million of school debt to pay off from a bond they sold ten years before. Their limited debt capacity prevents them from solving the space capacity, which is a structural feature of the problem with Mosley. They need the space! And they can’t create more space without going into more debt, which they can’t afford.

Meanwhile, they also need the money, since federal dollars are disappearing and older workers aren’t retiring fast enough to absorb the new hires they made with the federal dollars. This last point stands out to me as an underappreciated feature of the situation too. If people felt more secure in their retirement, would they retire? Are they living longer and wanting to keep working? That can be a stressor.

Add to all this the anti-migrant politics and it’s quite a situation. If there were public credit for public schools, there’d certainly be less tension at the county and district levels, and one would hope there’d be generosity of spirit and resources to bring more migrant students into the schools, but there’s no guarantee.

Incidentally, I don’t think Foust did himself any favors by speaking in neoliberal terms. He talked about how productive schools are, whether the school is a good return on investment. Listening to the meeting, I think this alienated him from other board members. I assume the conservatives on this school board were likely not well-disposed to a Black leader wanting to open a newcomer school, and it’s not clear that without the riverbed of the debt regime, this particularly flow of tensions would be different. Such is racial capitalism.

At the same time, I have to believe that a different structure for facility financing would make a material difference in these dynamics. I do think changing this riverbed would redirect the river elsewhere.