Railed

Happy new year! Things are still slow over here with a newborn, etc., so this week I’m sending along a section of an early draft of the piece I wrote on the municipal bond market for the Baffler. This historical bit didn’t make the final cut but I think it stands well on its own. I’ve also added a kicker using a sort of viral tiktok I made about the school finance history of a popular meme.

Meanwhile, if any readers happen to be in the vicinity of Paris, France, I’ll be giving a lecture at the Ecole des Etudes Sciences Sociales next Monday at 2pm. Would love to see you there!

Whence the municipal bond market that saddles public schools with so much debt? In a previous post, I did some diving into NYC’s school debt. This week I want to do a little history generally, since I get a lot of questions about bonds.

The few sources that attempt historical accounts all agree: no one really knows. It seems to have emerged out of the primordial political-economic goo of the post-revolutionary war period in the United States. There’s nothing like the municipal bond market elsewhere in the world, though its beginnings happened in finance capital’s cradle. History can create a sense of contingency, so here are some notes on what I’ve been able to glean.

According to Alberta Sbragia, whose work on this is the best, the Erie Canal project, one of the first big infrastructure initiatives of the infant United States republic, kicked off a mad competition between states to develop big infrastructure too—and since New York had used bonds to finance the canal, bonds became the default strategy.

But the municipal bond market as we know it —where the bondholder owns the fines and the municipality holds the tickets —was born on the rails. As railroad tracks crisscrossed the landscape, the method of financing them devolved to the local level. The rail company would go to the local government and say: issue a bond, help finance tracks, and we’ll build it. Whether the tracks got built was a matter of life or death for these conurbations, so there was a mad dash to take out loans throughout the 19th century.

George Russell in The Gilded Age television show actually makes most of his money from local municipal loan revenues paid to his company. The town sold the bond, gave the proceeds to the rail company, who built the track, and the towns paid back the loan to the bondholders (who’d put up the cash) with the resulting revenues flowing from business activity within their boundaries due to the railroad. At least, that’s how it was supposed to work.

What actually happened was a huge debt load, uneven success in construction, and not enough municipal revenue to pay back the loans in time, leading to a wave of defaults. The rail companies came and built the tracks—sometimes to nowhere—and then they skeedaddled out of town, leaving the city councils and mayors and local economies holding the bag.

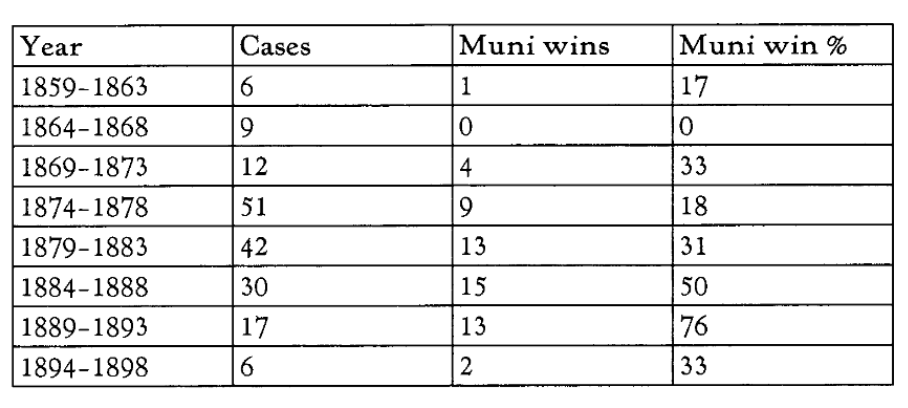

Municipalities started claiming that they didn’t have the obligation to pay these companies back, using a de vires legal strategy to say the initial bond contracts were void, signed under a false pretenses of public purpose. The towns argued that the rail companies were private companies and thus the money owed to the bondholders was private money, not public money. When they made this case in court, the municipalities repudiated the loans. This created a profound chaos in the pipes and plumbing of the country’s infrastructure. There were 203 repudiation cases at the Supreme Court between 1859-1899. Between 1889-1893 municipalities had a 76% win rate for these cases, which had stayed above 30% since 1869.

It was an inflection point, both for the configuration of the municipal bond market as we know it, but more generally for the difference between what counts as public and private. Either the court could find in favor of the people and protect them from the private railroad companies and their schemey grabs of municipal loan revenues, or protect the companies and bondholders from profligate and irresponsible localities.

The courts ultimately decided in favor of the bondholders. The towns had to pay up, or else. The cases, called the municipal bond cases, solidified bondholder supremacy in municipal finance, the same supremacy we face today, both in consolidating the repressive state apparatus’ protection of bondholders, and strapping down the state and local governments so they couldn’t repudiate again: the localities would have to secure a majority or supermajority of voter approval among taxpayers to issue new bonds; the localities could only maintain certain levels of statutory debt outstanding; the municipalities were forced to include debt covenants in the bond contracts promising to pay back bondholders before any other expenditure; and the towns and citizens and states were subjected to punitive credit rating criteria if there was any possibility of they couldn’t pay—their full faith and credit now lashed to the bond market and its cast of characters.

These restrictions set the warp and woof of the straight jacket municipal and state leaders must don upon election, the belts tightened by forces beyond their control.

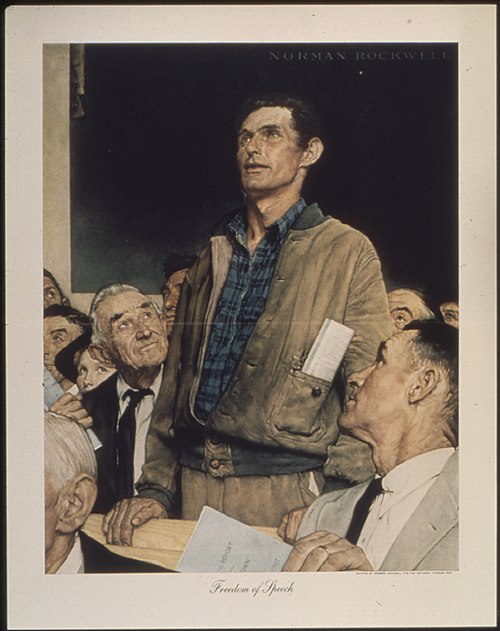

As a kicker, consider the now meme-famous painting by Norman Rockwell, Freedom of Speech.

On social media, when someone has an opinion that they want to express, even if it’s going to make people mad, they post this picture, produced to illustrate FDR’s four pillars of American society in the 1940s.

According to Brian Allen, this painting is actually based on a guy named Jim who spoke against the town of Arlington, VT selling a school bond to rebuild their local school in 1940. The building had burned down, and the way school infrastructure is financed in the US is through municipal bonds sold by districts, which are hemmed in by all kinds of restrictions, including requiring local residents vote in favor of selling the bond.

Jim didn’t want to pay more taxes. He was the only one voting no. Everyone else in the town was fine with paying more taxes to repay a bond to rebuild the school, but not him.

That situation—Jim speaking against Arlington voting to go into debt to rebuild their public school—was created by the ruling class response to the repudiation cases of the previous century brought against railroad companies. We inherit that regime today.