Pension tension

You've probably seen what's happening in France. Centrist president Emmanuel Macron forced through a change to French retirement age from 62 to 64, relying on an archaic protocol in French government that let him bypass votes in the parliament for the change.

In response, the French public have led an ongoing uprising involving mass strikes and disruptions to multiple industries and services. The change is part of Macron's larger attempt to reform French pensions. This got me thinking about what's going on with teachers pensions in the US, which is related.

Pension tension

A pension is money you get when you retire. As Michael Roberts puts it:

Pensions are really deferred wages, deductions from income from work to pay for a decent income when people retire. After decades of work (and exploitation), workers, male and female, should be entitled to stop and enjoy the last decade or so of life without toil, without being in poverty. Literally, they will have earned it. But capitalism in the 21st century cannot ‘afford’ to pay decent living incomes as state pensions when workers retire. Why?

In the US, pensions are rare. Whereas a pension pays you at your salary level after you retire until you die, we more commonly have social security, a federal program which provides payments according to certain percentages of the amount you put in via withholdings, when you retire, etc.

Pensions are almost exclusively limited to the public sector. Employees that don't work for public entities can have privatized retirement plans called 401Ks, managed according to variable rates and come with fees from the private banks that manage them.

It can all seem a little far away and strange to us in the US, particularly when France is more heavily unionized and has a much stronger tradition of striking, disruptions, and social upheaval in response to government incursions into the French quality of life. As they say, people in France work to live while people in the US live to work. Read the Sidecar piece linked above to understand that situation on the ground.

The tension with pensions is that the ruling class, using a neoliberal framework, doesn't want to pay for workers' retirements. It's too expensive, they say. The pensions are too big, they say. They're mismanaged, corrupt, inefficient, wasteful, etc. What they'd like to do is to make them smaller (by increasing retirement age, eg) or privatize them or similar measures.

So whenever you hear someone say "why don't the French people just retire a little later?" what they're really saying is "why don't the French want to be exploited more for longer?"

Pension debt?

But what's happening in France isn't so far away from us in the US, particularly in education. I wanted to connect what's happening in France to a similar-looking situation in United States teacher pensions.

While pensions are rare in the US, teachers are some one of the few professions--along with police, government workers, military, etc--that still have them. And it seems like they're headed towards a similar kind of place to the French situation.

Jess Gartner, Jason Becker, and Anthony Randazzo at Allovue--a private school finance consulting firm that sounds like a pharmaceutical company--posted an article looking at the coming pension debt crisis for teachers.

Since pensions are "defined benefit" programs, which means they pay out a specific amount to you, and school districts are the ones responsible for making pension contributions for their retired and currently working employees, the districts are on the hook for making a certain amount of contributions each year to keep up with the defined benefit.

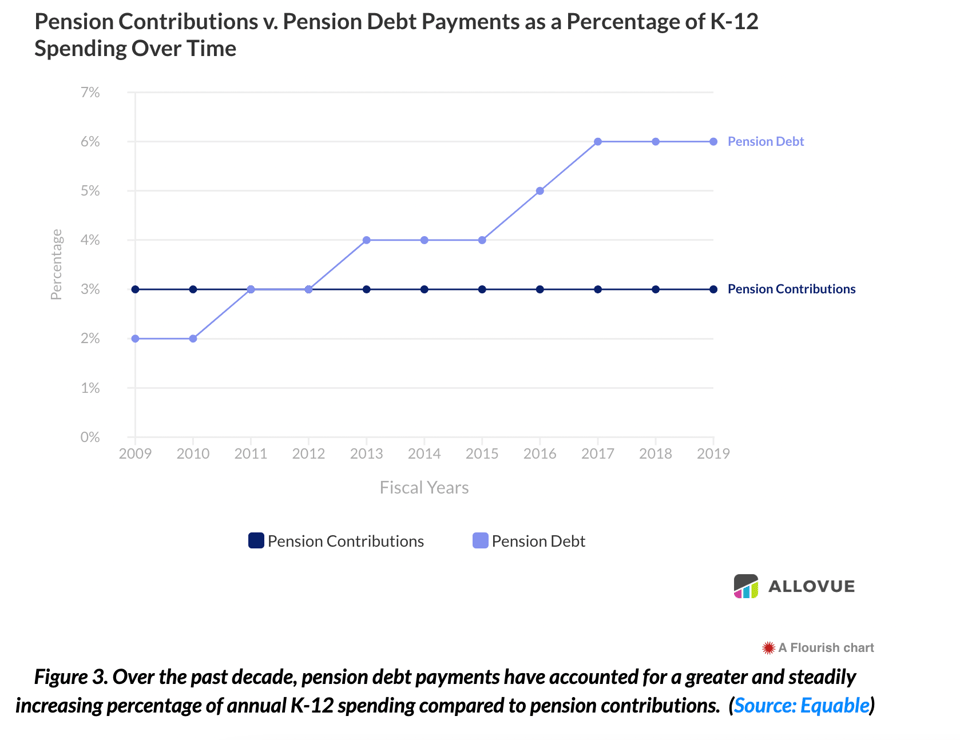

Pension debt happens when districts can't keep up with these payments. They owe the pension funds certain contributions but can't make the payments. The Allovue authors calculate that the public education system will be on the hook for around $600 billion in pension debt by 2030.

Retirement systems for teachers are assuming their payroll grows at 2.9% over the next decade, and whether using that rate or a more conservative 2% payroll growth level, projected pension debt payment between 2020 and 2030 are between $605b and $635b.

This amounts to a $600 billion budget cut to school districts in the next seven years. The authors contrast this to federal relief money through ESSER coming to school districts, which totals about $190 billion.

What's going on here? The Allovue people point to the mismanagement of pensions as the problem. They're not wrong I suppose when they say that unfunded pensions crush district budgets, and that having "candid conversations" around pension reform can sound "anti-teacher." Indeed, talking about messing with pensions arouses the same vital energies now shutting down France.

They retort:

You know what’s anti-teacher? Keeping teacher salaries flat for decades, maintaining a system that benefits the few at the expense of many, and risking the very solvency of public education— that is anti-teacher. The trend of pension debt as an increasing proportion of public school spending is not fiscally sustainable. We need to cut through the moralizing and have some hard conversations.

Let's talk about it

Their recommendations aren't terrible. They want (1) more transparency and dialogue about pensions, (2) use state general fund dollars for pension debt payments rather than district dollars, (3) adopting more realistic assumptions for investment to make returns, and (4) get more creative for how pensions work for teachers, like what South Dakota and Colorado do (adaptable pension design) or the hybrid plans in Michigan, Oregon, and South Carolina.

I have to look at each of these designs to make sense of them. Like everything in the US, there's a dizzying difference between state policies. And pensions are confusing!

But the rebellions in France are a helpful reminder that pensions are our future wages and doing stuff to them is just as political as what capitalists do to present wages, and if socialists want to sit at the table and wield state power in the United States we have to know about pensions and come up with creative proposals for how to administer them so they benefit the working class.