Pasadena's path through the crisis

Written with Alan Gao

There are school closures being threatened all over the country, and even more budget crises. At this writing, besides some general coverage, there’s no national map or coverage of school district budget crises, shortfall numbers, closures, etc. There should be. From my informal work on tiktok taking requests to look at district budget kerfuffles, I’ve got a list of 60 requests. Whenever I look at one district, I get comments from people asking me to look at theirs, which tells me that there’s a national wave of school district crises that’s building.

I get asked a lot what people should do about these crises. It’s a tough question. I usually give them a pitch about green fiscal mutualism sponsored by Inflation Reduction Act programs, encouraging people to demand that districts decarbonize their capital plans, saving money in the long run through lowered energy costs and in the short run with reimbursements through federal tax credits and capitalized green banks. But who the hell knows what’s going to happen to these programs when the next Trump administration comes in. UnDauntedK12, an inside-track nonprofit doing good work connecting districts to IRA programs, is cautiously optimistic in a recent email to members, and I’ve seen how much conservative districts benefit from these programs, but I can’t help thinking the IRA’s generous provisions for local governments will go the way of Build America Bonds. Maybe they’ll cut it out of pure spite.

But there’s something interesting happening in Pasadena. Here’s a district with a huge budget shortfall that, from what we can tell, is more or less due to state budget rollbacks. But the district is using the crisis for something interesting that I wanted to highlight as a sort of path through their budget crisis, which maybe other districts can emulate.

Sad unrestricted fund

This year, the mid-size school district outside of Los Angeles faced a more than $50 million budget shortfall. More than half of this gaping hole came from reduced state grants, which fell by $32 million. Add in a 20% enrollment drop, about $4 million less in federal relief monies, and a decrease in local revenues, along with a big net pension liability increase ($80 million from 22-23), and you’ve got a district with a big crisis. The district is also paying about $8 million in debt service each year to Wall Street.

It’s a mixed situation. They ultimately fired around 180 people last year, balancing budgets through this year despite these decreases and, it turns out, giving the people they kept a nearly 30% raise over the last three years, drawing from confidence in those COVID relief monies (tragically, those raises seem to equal the amount of the budget shortfall). But now, they’re worried about another big shortfall in 2026 that they’re trying to address in advance.

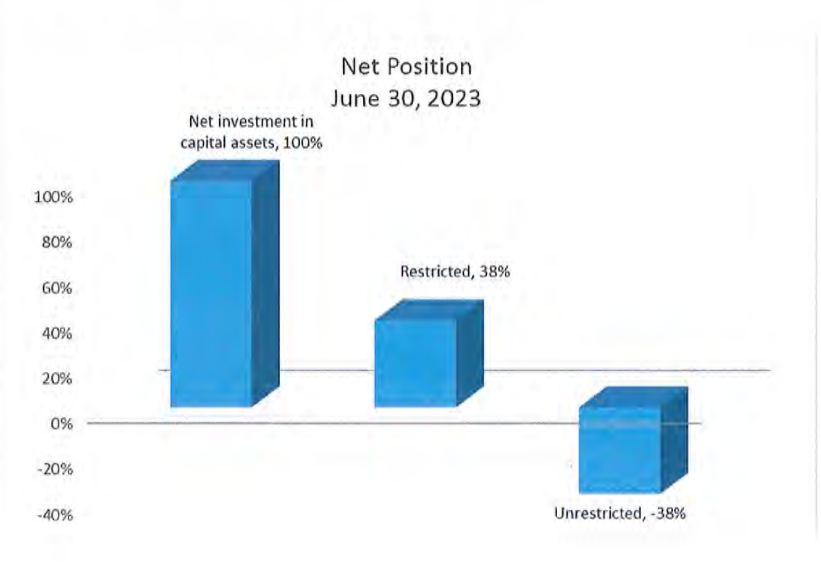

Just to get into the weeds a little bit on their crisis, there’s an important dynamic happening between the district’s restricted and unrestricted funds in its budget. An unrestricted fund is basically your bank account that you can use for any purpose, it’s the money you’ve got socked away at the end of all your expenditures. The restricted fund however is money for specific purposes: you set that aside to pay for particular things, you can’t dip into it and you really have to pay what you plan to pay with that money. In Pasadena:

For the Unrestricted General Fund, the district expects to incur $191 million in expenditures and collect $213 million in revenues. However, after a $60 million transfer to the restricted general fund for special education and routine restricted maintenance, a $38 million deficit remains.

…the district budget team said the $38 million deficit in the unrestricted fund is their primary concern, rather than the $50.7 million overall deficit. This is because restricted funds, unlike unrestricted funds, are designated for specific purposes and there’s no expectation to keep them.

So actually the unrestricted fund is getting more than its spending, but it has to make a transfer to the restricted fund, which then gets it in the red. There’s a very sad graph of this unrestricted funds problem ina recent audited financial statement.

Let’s look at this transfer between the funds, since it seems to be the source of the fiscal pain. According to the reporting, there’s a $60 million transfer for “special education and routine restricted maintenance.” In the audited statement, I see a big jump in plant services from about $30 million to almost $50 million. Turns out the district is going to float a $900 million bond for their buildings and facilities (backed by the success of the state’s recent proposition to do a state bond for school infrastructure, hopefully), so yeah, they’re doing a lot of work on the buildings. I can’t see the special education expenditures broken out, but those monies may come from the state, which is also in a budget crunch.

In any case, rather than a state funding story, I think this is a facilities and special education story, which is an important insight in how the district constructs its budget crises narrative and communities push back against their plans to cut and fire.

It’s a dire situation. But there’s a kind of hope amid this crisis, which is something I rarely find.

Make the school a home

California has a law called AB 2295 that provides a bunch of incentives for school districts to develop affordable housing using their property. There’s also another law that lets entities like districts get faster approval for building this affordable housing. Pasadena Unified voted recently to use these statutes to build 115 affordable apartments for school staff and faculty in what was Roosevelt Elementary school. Half of these units will be low income housing.

A survey had found that 70% of district employees paid 30% or more on their rent. With housing so expensive, families couldn’t stay in the district. By turning the old school into low-income housing, the district will bring in about $1.5 million in revenues a year and be able to make it more attractive for staff and faculty to live in the district, hopefully stemming enrollment declines.

One of the board members put it very well:

“We’re changing a liability into an asset,” Cahalan said. “This is turning a negative cashflow asset on the books into something that generates funds for the district.”

As school districts around the country get ready to face their budget crunches, I think they could learn something from Pasadena. Of course, AB 2295 might be a unique law. But this legislation could give people elsewhere in the country something to fight for. Get one of your favorite elected representatives to write, sponsor, and pass legislation to let school districts build low-income housing using district property, then have the school board vote. (There may even be federal or state green bank financial instruments that can help the district save money on the development by making the housing green, something for me to look into.)