On being well-endowed

As a preface to this post, for higher education finance resources and organizing help you should check out Scholars for a New Deal for Higher Education, particularly Salem State's debt toolkit, as well as the Debt Collective and the Public Higher Education Workers network.

***

I made a tiktok about the financial situation at the University of Connecticut. It got more attention than I anticipated, and I started getting comments asking me to look into other university finances where administrations are crying crisis. One commenter asked me to look into the University of Chicago’s budget issues.

It’s coming up now because the graduate students at UC just won their first union and they’re negotiating their contract. They’re looking for stipend increases, but the university is pushing back because, they say, there’s not enough money. There’s a $239 million budget deficit they’re dealing with. Let’s look at what’s happening.

There’s been a lot written about the story how this deficit happened. The bottom line is that the endowment has been underperforming and the administration has been behaving badly. For elite private universities, their endowments are super important financially. I heard recently on a business news podcast that Swarthmore College gets more than half of its operating revenue from its endowment investments, which are managed privately. If you’re a private school and don’t manage that endowment well it has big consequences for your budget.

University of Chicago made some..missteps with its endowment investments over the last few years. A classics professor named Clifford Ando has written extensively on this mismanagement, and the university’s paper the Maroon has solid reporting on the overall situation.

In 2022, the endowment lost 8.8%. That’s bad. The compound measure of the endowment’s growth was actually double that at -16.4%. Bad bad. Why? An independent financial analysis diagnosed four reasons, but the primary one was

overexposure to emerging market equities (the worst-performing asset class) and underexposure to real assets and private equity (the best-performing asset classes). This continued a trend over the past ten years of less liquid asset classes outperforming more liquid ones, result[ed] in the endowment’s current situation.

I’d like to know exactly which ‘emerging market equities’ they’re talking about here. Like, what’s an example of a ‘less liquid asset class’ in terms of their investment strategy? And what’s the board doing about this now? I’d maybe get some business students to ask about this.

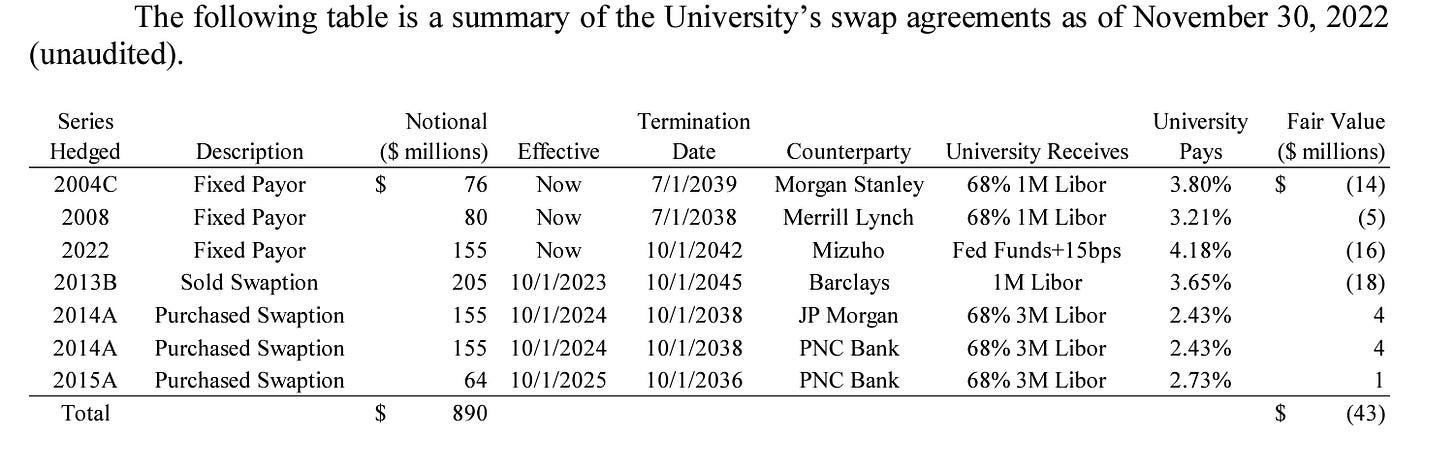

For instance, I found some information about the swap agreements (variable rate deals) the university has done. I don’t have the chops to examine these for funny business—all swaps are sort of funny business, but they’re not necessarily illegal or technically bad by themselves, I guess?—but I put them here for others’ perusal. I guess I’d ask about the relatively high percentage of university payment to Mizuho (4.18%) on Fed funds+15bps on a fair value of -$16 million in 2022. Ando doesn’t get into this stuff. How was that deal negotiated?

In any case, this shit matters. Ando found in his analysis that

the University’s debt grew from $2.236 billion in 2006 to $5.809 billion in 2022, which represents an increase of 260 percent. [Amounting to 68% of the current operating budget, double the typical amount at an Ivy.]

High levels of debt present a financial problem for the University because of rising interest payments. The University paid $45.7 million in interest payments in 2006. Ando claimed that payments averaged $200 million in 2021 and 2022.

Apparently base compensation has risen 285% for the university’s president since 2006 too. Ugh. Read the full Ando essay here. It’s worth it for both its analysis and its flourish. It’s full of gems, like how the university spent $3 million on the president’s house, which is more than the research budgets of 250 faculty in theology and the humanities combined.

Yet the university is still talking about cuts, including the ominous “potential sunsetting” of certain programs and now will most likely refuse cost of living increases for newly unionized graduate workers.

But while I’m curious about the story here, I’d like to open more avenues for questions as the grad student movements—and faculty and other students—push back against the trustees’ and administration’s actions to cut their programs.

I found a recent bond statement for the university and I’m digging through it to that end. I’m interested particularly in the structure of the endowment, what money is where, and how that flows into the operating budget.

Generally I think this situation is a case of endowment politics: how has the university managed its endowment, and how could it manage this endowment in a way that’s more generous and friendly to its own academic community and mission? The bond statement has some information to answer that.

Well-endowed?

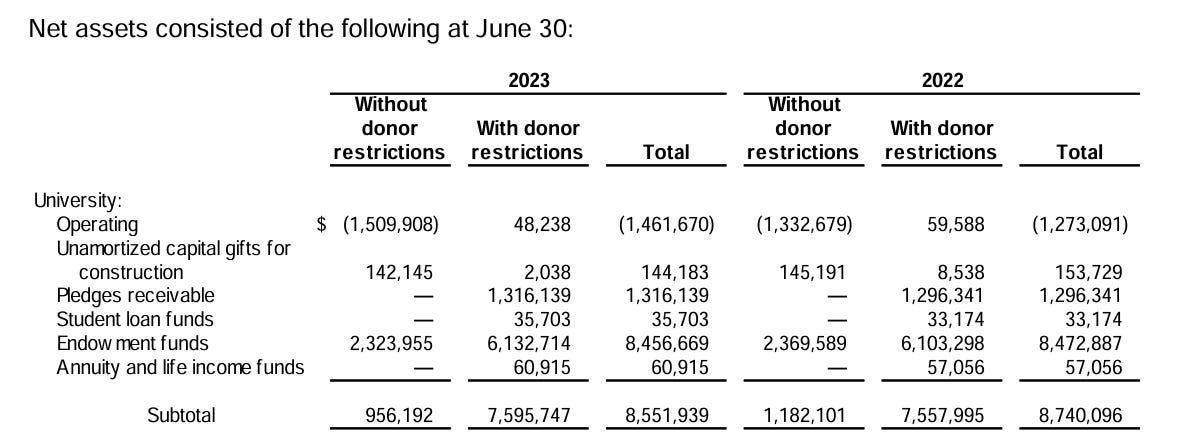

What do we mean when we say ‘endowment’ anyway? When it comes to UC, it’s actually 4,500 different funds “established for a variety of purposes.” There are at least two kinds of money in this massive set of funds worth more than $10 billion, which operate a lot like restricted and unrestricted money in public budgets: donor-restricted “true” endowment funds and funds designated by the Board of Trustees as “funds functioning as endowment” (FFE). Some endowment money is limited by donor-imposed limitations, and some isn’t. What’s the mix exactly? Do we get to see that? In breakdowns, I can find big mixed numbers but nothing at the granular 4,500 level.

The endowment is also split up into three different endowments: university, medical center, and marine biology laboratory (MBL). Yet these endowments are mixed together, which is called the Total Return Investment Pool (TRIP). Aside from the restrictions placed on what the money can be used for, the next most important policy is how payouts from the endowment get calculated.

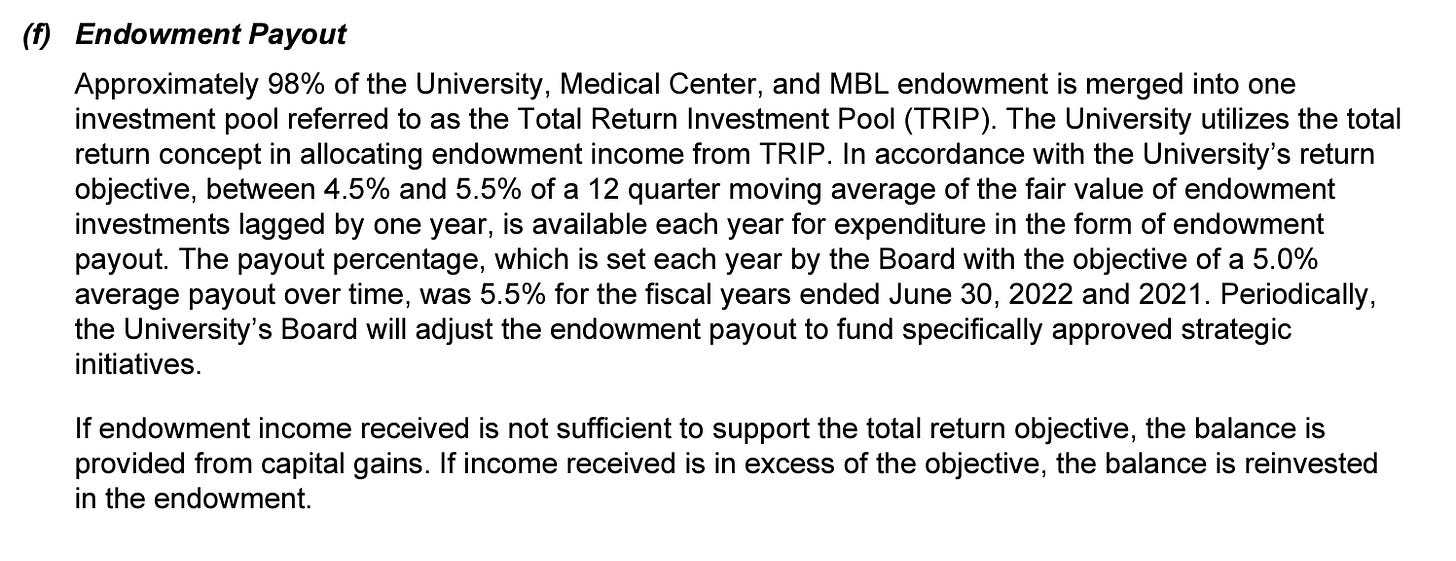

When paying out from the endowment, the administration has certain policies in place. They decide how much money should be used from the endowment for any given year’s expenditure. This is accordance with a “return objective” stipulating what’s available for expenditure each year to be

between 4.5% and 5.5% of a 12 quarter moving average of the fair value of endowment investments lagged by one year

That payout percentage is set by the Board and has been as high as they ‘can’ go, 5.5% for the last two years. But what’s that percentage been over the last few years? And if they wanted to, could they increase that threshold and payout more? Or change that “return objective” to a differently configured quarterly moving average—or a different value structure other than fair value—or lagged by a different year, etc? How did they decide all that?

In terms of one avenue for questioning, specifically rooting out the places where the administration has relative autonomy in its usage of funds available to it—as opposed to cutting—I found language that says “periodically, the University’s Board will adjust the endowment payout to fund specifically approved strategic initiatives.” Again, does this mean that, if the Board wanted to, it could increase the endowment payout?

All this language comes from this part of the bond statement’s financial reporting on the university:

So one initial question I’d ask is whether and how the administration and Board want to be well-endowed. That is, are they willing to think generously and creatively about the endowment’s payouts to guarantee, for instance, that graduate workers—with whom they must bargain in good faith—have a living wage? I want to study the actuarial technicalities and ideologies here a bit more, but it’s a first instinct as I’m reading. More on the situation soon.