NYzantium and the politics of weights

I've been living in Brooklyn the last few months as part of my academic sabbatical. The school district here is wild, serving just under a million students in nearly 2,000 schools. It's budget this year will be $37 billion. It's the biggest in the country. It's like a country itself.

I've been looking for ways in to understand it and I found one. Something interesting is happening here in the next few months. The school district's organizational structure legislation is coming up for a vote in Albany, since it's the state that decides how the city runs its schools. Michael Bloomberg centralized the district in 2002, but there was significant pushback in the last extension to the policy of mayoral control. Next year, the way the district itself is organized--the way political force flows--will either be reupped or redone.

Since socialists have a significant presence here, the question has come up in some corners about what a socialist vision of the school district's structure could look like. I've ventured some thoughts on this question, but these thoughts are provisional because I have only a basic understanding of how the district works. This post is partly to check my understanding and partly to float some of these provisional thoughts on this huge question.

NYzantium

The city's district--which is actually composed of 33 districts, 31 regional and two others by service provision--is run through mayoral control. That means the ultimate decision-maker for district-wide policy isn't an elected board that votes on the policy, but rather the mayor, who gets their recommendations from a chancellor. The chancellor, under whom a number of deputy chancellors work, gets recommendations from their underlings, including a byzantine network of policy boards populated by volunteers; parent associations; school-based organizations; the United Federation of Teachers; etc.

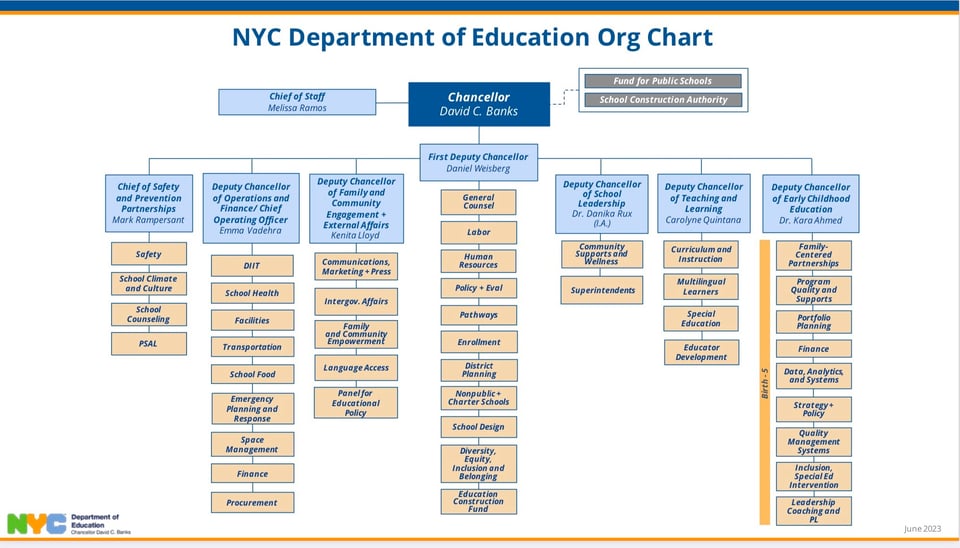

The district provides an org chart, which is, indeed, very top-down:

One of the deputy chancellors oversees a group of superintendents because every district in the district has its own superintendent. School principals report to this superintendent. The principals get feedback from parts of that network of organizations/advisory groups; the superintendents get feedback from the groups and the boards; and they all provide feedback to the deputy chancellors who advise the chancellor who advises the mayor. (This doesn't mention the union, the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), and the caucuses within the union. I can get into that later.)

#standwithTajh

Let's take a look at this byzantine structure from a movement perspective. Every district in the district has a Community Education Council (CEC) that advises a citywide council, all of which advise the citywide Panel for Education Policy (PEP), which then advises the chancellor. Here's how CECs work, from CEC 14's website:

New York City’s Community and Citywide Education Councils are charged with promoting student achievement, advising and commenting on educational policies, and providing input to the Chancellor and the Panel for Educational Policy on matters of concern to the district. The powers and duties of CECs are spelled out in NYS Education Law §2590-e; those of Citywide Councils can be found in §2590-b.

The Community Education Council (CEC) is made up of nine (9) volunteer parents from District 14, who are elected for two-year terms by the parents of children in District 14 schools and two (2) volunteer members who are appointed by the Borough President. One additional member is a non-voting High School senior. Elected parents must have a child in a district school grades PreK – 8. Certain community members, including charter school parents may apply for an appointment by the Borough President.

The CEC websites and social media accounts all have the slogan "we're your school board!" That's because the CECs are the closest thing that the district has to school boards. But they don't decide policy.

Despite their not having formal decision-making power, CECs are in the spotlight now. The rightwing New York Post recently reported that Community Education Council (CEC) 14 advertised a student walkout in support of Palestine and shared resources on the Israel-Gaza war, some of which used the conjunctural slogan "from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free".

The Post focused on rage against CEC14's elected leadership, especially its president Tajh Sutton. There was a petition to remove Sutton and the other leaders. In response, there was a #standwithTajh movement to support her. In a centralized structure like the district, everything comes back to the chancellor, David Banks, who made a milquetoast statement and didn't comment for the article.

In a follow up article reporting on a contentious CEC14 meeting, Sutton said "We already had our mayor, our chancellor, our governor, and the US president stand with Israel . . . we are unpaid parent volunteers that saw a gap being created by leadership.” The CEC only has a small advisory capacity in the byzantine apparatus of the NYC district, but as you can see also exerts a nonzero energy in the city's balance of forces. Sutton showed remarkable bravery and courage in the onslaught by using her position to push for ceasefire, pressing on that pressure point. (I'm living in District 16 at the moment and tried to attend the CEC14 meeting. But when I tried to join they wouldn't let me enter. Meanwhile, My CEC's website doesn't work.)

Movements are great ways to demonstrate the relative autonomy that parts of an apparatus wield, and the CEC--sort of like a local school board for districts that compose the school district, but declawed of any influence over policy--is a centerpiece of participation in a larger non-participatory structure.

The politics of weights

What could a more socialist vision for the school district structure be? In debates I've heard thus far, the typical positions are to either keep mayoral control, which is centralized and therefore undemocratic, or get rid of mayoral control in favor of an elected school board, which is decentralized and more democratic. There a ton of presumptions here: mayoral control = centralization, decentralization = democracy, eg.

I'm not sure these all line up the way they're supposed to, particularly for the NYC district, which is like a city-state. Even the district has districts! What I do know is that socialists usually focus on what's best for the working class and, what's more, making sure the working class has more ownership and control of the means of production throughout society. What school district structure would best serve the city's working class?

Generally, I think a proper state is one where the apparatus has legitimate authority in its territory among its population. The NYC district needs something that'll work for its people in its place. For that, I imagine something like a congress with delegates that can pass policy. The delegates would come from the schools themselves. The question then becomes apportionment: how many delegates do certain schools get. For that, the socialist approach would be to follow the struggle over material conditions of educational existence in the city.

One of the city's biggest problems is inequity by race/class demographics. The schools in the city's poorest, least white areas get less money per pupil. One reason for this disparity has to do with a recent shift in the city's school funding formula.

Because the district is more like a state government than a local government, at least in terms of number of schools and students, it has a funding formula that distributes money to each school building like a state would distribute to districts. And like those formulas, the district's formula went from a nonweighted calculation to a weighted calculation, taking into account differences in the school populations, like demographics, language learning, poverty, etc.

One thing that happens when states make that transition from nonweighted to weighted is something called hold harmless policies. This policy stipulates that schools can't get less money than they were previously alotted between fiscal years. If a school gets X one year, then it can't get less than X the next year. The money is held for them no matter what, changes in their enrollments are harmless to their appropriation.

Hold harmless policies are harmful. Since education budgets are limited in their total amounts, it means that a chunk of money has to go to districts no matter what--even if a new funding formula has weights for poverty. This happened to NYC. According to a recent study:

Much of the funding discrepancies can be traced back to NYCDOE’s decision to minimize the impact on schools that had previously been overfunded by providing “hold harmless” concessions “for 661 schools [which] cost the district $237 million, more than twice the cost of increasing funding” for the 693 schools that were considered underfunded and that received $110 million under FSF (Childress, 2010, p. 226). In analyzing the implementation of FSF, the NYCIBO (2007) notes that on average, the 661 schools that were overfunded received $358,332 in “hold harmless” funds, while the 693 schools that were underfunded received an additional $158,703 in funds. (23)

In the previous formula, some schools were overfunded. When the new formula came through, those school budgets were protected. Their money was held harmless. And the differences didn't get fixed. On top of that,

In a move that would maintain this educational inequity, no underfunded schools received their full FSF formula budget because the schools that were underfunded were capped at either 55 percent of their total FSF need or $400,000, whichever was lower. Overfunded schools had no such cap, which meant that they were able to maintain their full level of support.

That flaw continues to resonate over time, the injustice maintained. So here's the beginning of an idea. Funding formulas are largely economic, but they have a politics too. Economically, the formulas are trying to compensate for differences in those student populations. Those school communities deserve more funding than they've had in the past as a result of historical structural features of their social context.

The political implication of that compensation is that these school communities also deserve more power in the procedures that govern their educations. In the struggle for working class power, they've been at a disadvantage.

A City Education Assembly could vote on district matters like a congress. Each district, led by the CEC, could elect delegates to the assembly from the schools. How many delegates will each district get? By population, like other governments. However, there should be two further criteria for delegate apportionment: (1) districts with higher scores on their weighted FSF allocation will have proportionally more delegates (we would need to work out calculations here, like every point added from formula weights yielding one more delegate); (2) districts that have suffered from hold harmless disparities will have proportionally more delegates, according to a calculation.

A delegate assembly whose delegates get apportioned according to weighted funding formulas might ensure that the diverse working class gets more political power in the decision-making over policies in their district. But again, I need to read much more!