Notes on disclosure and divestment

As the student movement against genocide in Palestine continues around the world, one of the key demands made by activists and their coalitions has been disclosure and divestments of university resources related to Israeli military action. I don’t have much to add to these ongoing initiatives, but as an American Jew that researches education finance, including higher education finance, I have looked into some of what disclosure and divestment might look like, as well as obstacles to them, and other details, so I thought I’d jot down some notes in case they’re of interest or helpful.

Students have taken up and taken on the powerful and dense apparatuses involved in NATO’s financial flows to Israel. In higher education one of the most explicit touchpoints is the endowment, huge pools of capital that US universities—both public and private—invest in various markets and assets to bolster their savings, plan for capital programs, and fund operations.

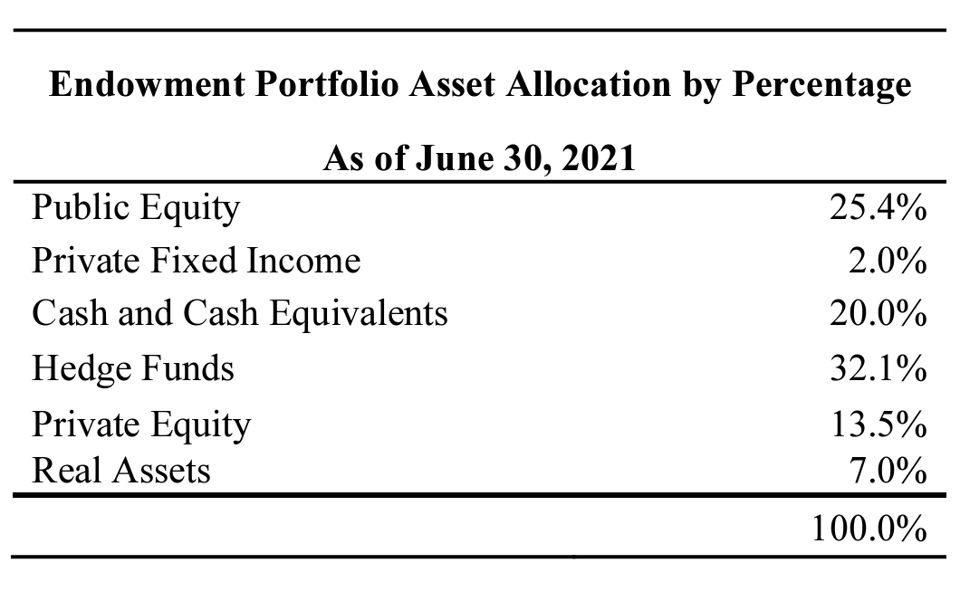

These endowments are typically managed by subcommittees of the university board of trustees, who in turn hire financial consultants to assess the funds’ health and ensure maximum returns following actuarial protocols. As a rule, the itemized composition of investments in the funds are difficult to access. They’re hidden. What one can find are overall percentages of endowment investments. I’ve looked at this for several universities and get to the same dead end every time, but it’s helpful to trace them nonetheless.

The New School

The most recent case I looked at was The New School, where there’s a unique faculty encampment currently ongoing in solidarity with student actions. I found bond statements and financial disclosures for TNS through the New York State’s Dormitory Authority, which does bonding for public and private universities in the state. The disclosure says that the endowment at TNS is currently worth $464.8 million.

The bond statement has details about the endowment, but like in every case I’ve seen, stops at a breakdown into certain categories.

As economist Daniela Gabor mentioned in a tweet about Princeton’s endowment, it’s usually in the private equity and hedge funds that notable and problematic investments would be found. But we don’t know what those actual investments are: who are the companies, funds, etc. where the money goes. (I was able to see some details on University of Chicago’s endowment activity, specifically the firms and trade structure of swaps they did, which could lead to more information.)

The TNS bond statement does tell us that as of 2021 there was $65 million in hedge funds, real estate, and private equity, so around that number might be invested in things related to genocide. But we don’t know. Thus the importance of the disclosure demand: make these numbers public so we can see.

So who has access to the numbers and what would it take for them to disclose? These would also be the same people making decisions around divestment. Doing a bit of organizational mapping is a next step.

In the case of TNS, we see that the endowment is managed by the Investment Committee (IC) of the Board of Trustees. The bond doesn’t list that subcommittee. But a search for information about it brings up a couple interesting things. The university’s page for investment and risk management tells us that the IC is advised by an Advisory Committee on Investor Responsibility (ACIR), whose mission is to

develop strategies for incorporating consideration of social, environmental, and corporate governance (collectively "ESG") issues into the management of The New School's investments. Issues under consideration include but are not limited to: human rights, labor standards, environmental sustainability, equity, diversity, discrimination, and corporate governance and disclosure. Authorized by the university Board of Trustee's policy and procedures on Investment Responsibility, the ACIR presents recommendations on ESG issues that arise in the management of the university's endowment to the Investment Committee of the Board of Trustees.

If there’s anyone who would consider disclosing and divesting resources related to genocide, it would be this group. Interestingly, the website for ACIR in TNS’s internal site is broken. But a simple search for it brings you to a google site external to the TNS website that has details, including the composition of ACIR (at least as of the most recent updating of this external site).

Two names stand out to me: Bevis Longstreth and Scott M. Pinkus, the ACIR members who serve on the IC. Their biographies are colorful to say to the least, including connections to Goldman Sachs and other big financial firms. They sit on ACIR with students and faculty. I wonder whether they’d be open to dialogue about disclosure and divestment?

I mention these things as an example of what it would take to move forward on these demands. I imagine activists at the encampment know these things and are further along in their planning/strategizing. The movement is pretty sophisticated on this issue. Some encampments have already secured promises from their Boards of Trustees to bring these demands to a vote (Brown), or in some cases promises to divest.

Israel bond questions

While I don’t know the specific mix of university investments that could be earmarked for divestment, and thus requires a disclosure step, I did come across a specific financial instrument that, if pursued by organizers, might skip the disclosure part and get right to divestment.

Israel bonds are one funding mechanism for state governments, pensions, and private firms to lend the Israeli government money and then make money when Israel pays the principal back with interest. An Israel bond is an investment in Israel with which universities, municipalities, and other institutions and apparatuses around the university might be engaged, sending resources to Israel and then profiting on the interest payments.

I found a document that specifies criteria and protocols around the sale and purchase of Israel bonds. I have a couple questions I haven’t been able to find answers to yet, but look to me like the rudiments of a divestment campaign. One section in particular stood out to me:

Israel is a foreign sovereign state and accordingly it may be difficult to obtain or enforce judgments against it.

Although Israel has waived its sovereign immunity in respect of the bonds, except for its sovereign immunity in connection with any actions arising out of or based on United States federal or state securities laws, enforcement in the event of a default may nevertheless be impracticable by virtue of legal, commercial, political or other considerations. Because Israel has not waived its sovereign immunity in connection with any action arising out of or based on United States federal or state securities laws, it will not be possible to obtain a United States judgment against Israel based on such laws unless a court were to determine that Israel is not entitled under the United States Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976, as amended, to sovereign immunity with respect to such actions.

My questions are about the bolded text above. What does it mean for Israel to “waive its sovereign immunity with respect to the bonds”? Is that common in the legality of purchasing a foreign country’s bonds? I find it interesting that Israel’s sovereign immunity, so frequently cited in statements about the country’s making its own decisions about its defense, is porous in the case of Israel bonds.

Second, when they stipulate that one could obtain a judgement against Israel if “a court were to determine that Israel is not entitled under the United States Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976…with respect to such actions,” what do the laws say about being entitled to its protections and what could be the purview of the term “such actions”? What would court cases in this vein look like? Under what conditions could a legal entity in the United States—say a union that has come out in favor of a ceasefire—bring suit against Israel for its actions in Gaza, and get a judgment on the legality of a set of Israel bonds?

I ask because to me that seems like a plausible legal pathway for divestment that doesn’t involve the politics and protocols around university endowments, which potentially could go beyond the campus’s finances into the local, state, and even federal governments’ flows of resources to Israel. I have to investigate the questions above further but after asking a few people I haven’t gotten any clear answers. Stay tuned, I may have more next week.