Notes for a critical history of Philly's school buildings

Every year, Philly schools have to close when it’s hot. That’s because they don’t have proper air conditioning. But for some reason, this year, when the district had to close 63 schools early due to heat and improper cooling and ventilation infrastructure, people took notice. On the occasion of this renewed interest, this week I’m sending along a brief critical history of Philly’s school buildings.

The following are unpublished notes from background research I’ve done in the past towards a critical history of the city’s school buildings. It’s not meant to be exhaustive at all, but rather a sketch using past and contemporary sources. Apologies for the length, but that’s academic writing for you! I wanted to put this out into the world as a reference.

***

The problems with Philly’s school buildings, in kind and quantity, are far from new. Philadelphia’s school buildings have always been dynamically situated in the larger social-political terrain of the city. There was always a divide between the fantasy of these buildings and their material reality. In the 19th century, school planners thought buildings should be “conducive to the elevation of taste and the softening of the character of the scholars” and that in their “substantial construction…should be a lesson to the pupils of stability and honest worth.”

In 1855, it was agreed that 65 degrees was an ideal classroom temperature and that “proper circulation of air was essential to pupil health” (Cutler 1974: 383-5). At the same time, architecturally at least, from the buildings’ very beginnings, “[t]he elite were aimed toward high status and the professions, while the children of the working neighborhood would end up in the mill” (Thomas 2006: 224).

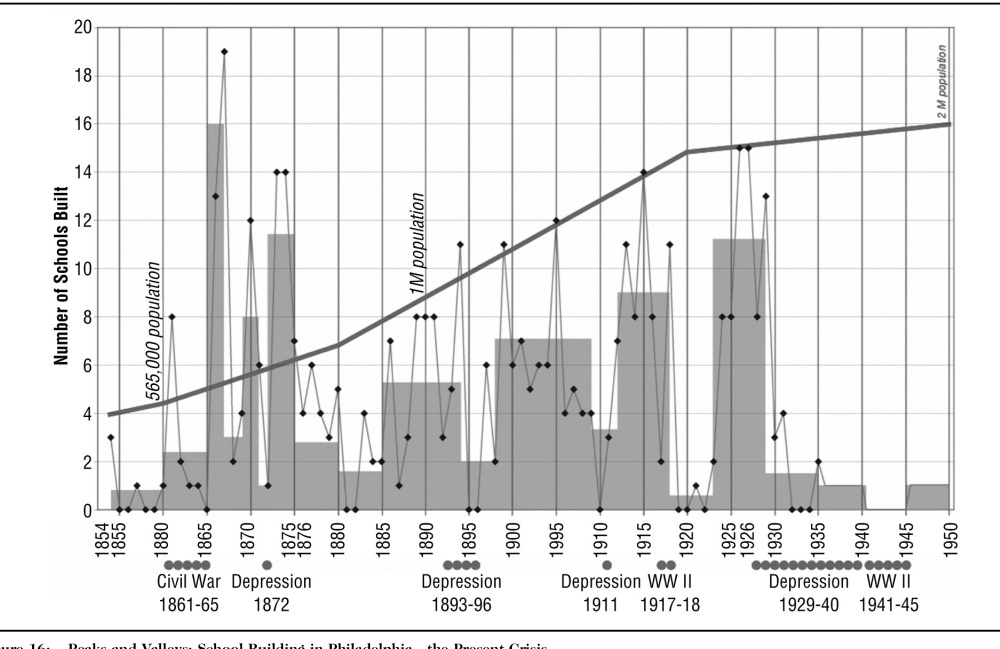

Despite lofty goals, the schools served the city’s class structure, never really keeping up with population, leaving the working class behind. During the mid-19th and early 20th centuries there was an acute enrollment crisis (Cutler 1974: 390): lack of classroom space for the growing city’s student population. For decades, there was not sufficient room and construction could not keep pace. The cracks in officials’ rosy fantasy constantly made themselves known, sometimes literally. In 1906, “Furnaces and ventilators were in disrepair, and the board of health had ‘repeatedly condemned’ the sanitary arrangements in several old schools. In some buildings, the floors were ‘splintered and dangerous” (Cutler 1974: 396). Details from a 1922 assessment were dire:

The general condition of Philadelphia’s school plant is deplorable… Dirt was everywhere, and in most cases there was no filthier place than the outhouses which still serviced more than half of the city’s elementary schools. In the opinion of the surveyors, ventilation was unsatisfactory in 72% of all classrooms, and below the high school level most pupils depended on natural light, which was generally insufficient. Desks were not usually adjustable to the size of their occupants (Cutler 1974: 397)

With only natural light to learn by, bad air, overflowing outhouses, splintering floorboards, badly fitting desks, the solution in 1922 was to finance repair, replacement, and new construction. But the money was not there.

Cutler tells us that “funds had always been a problem…In 1870, when the board requested $750,000 for capital expenditures, the city council came up with only $500,000.” The costs for capital expenditure would only increase and the lag would continue through the decades. “That not enough was done is apparent even now” (Cutler 1974: 398). He concluded his account of the city’s school buildings with a haunting imperative:

A schoolhouse should be more than a shelter; its design should complement the methods and goals of teachers and children. But it is also a long-range investment, and to a degree the attitudes, values, and standards of past educators remain standing for us to see. (Cutler 1974: 397)

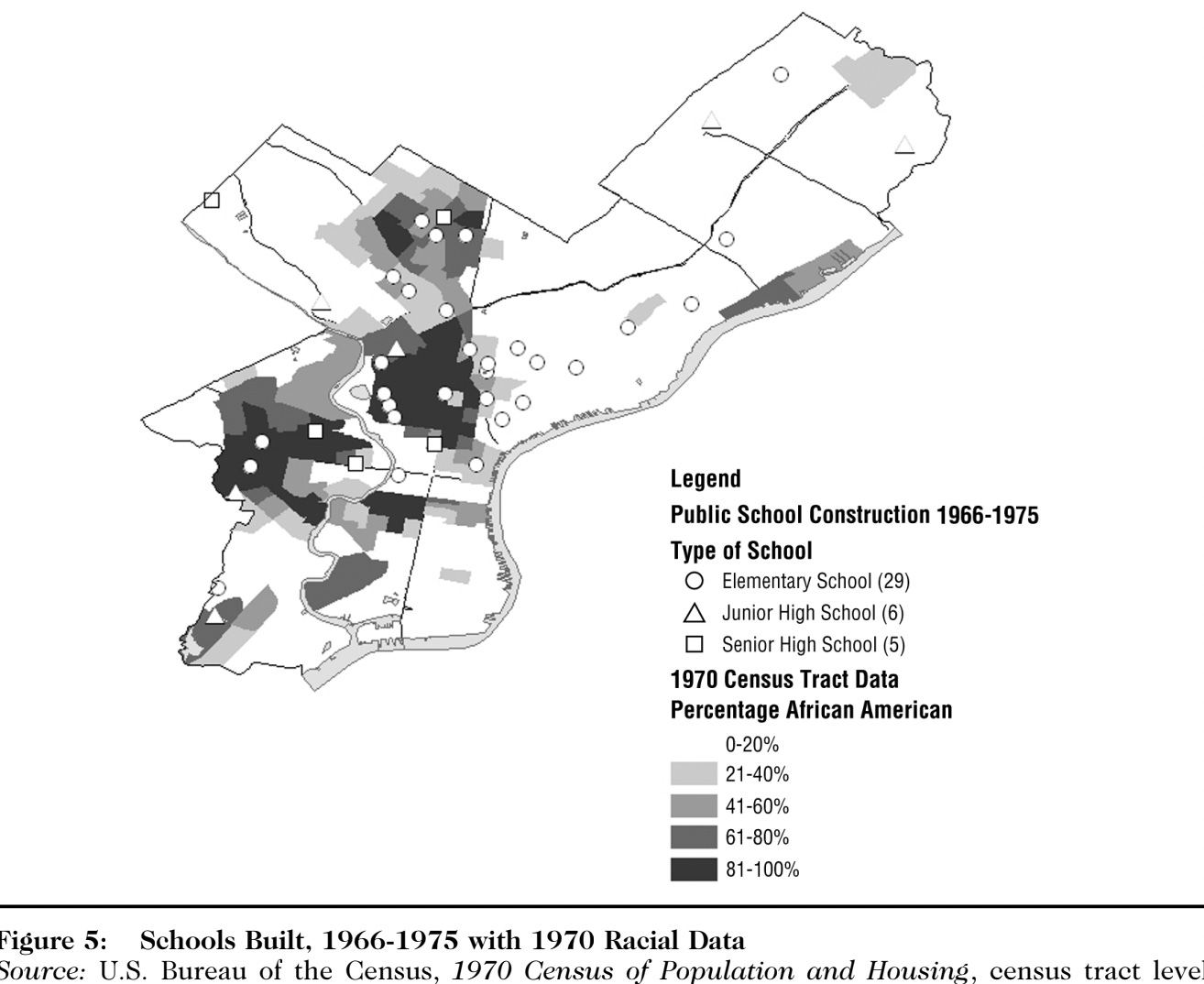

Thomas (2006) shows us that the attitudes, values, and standards across the last century and a half was class division, crisis, lagging facilities infrastructure, and, as Cutler confirms, under-investment. There were other values built into the built environment in Philadelphia, namely racism. Kitzmiller and Rodriguez (2021) have argued that “the toxic school conditions that exist today are intimately tied to class-and race-based inequities in the history of the built environment and historical inequities in school funding policies and practices” (1). Clapper (2006) shows that the “site selection, design, and construction of public schools reflected the everyday relations that slowly hardened into the structures of inequality” focusing on postwar century school facilities policies in the city. The district only stopped officially segregating school buildings in the 1930s (Clapper 2006: 247). His overall thesis is that the majority of new school construction in this period focused on the interior-suburb of the northeast section, which was predominantly white, while other neighborhoods did not see as much capital outlay. “Even as neighborhoods changed as a result of migration and urban renewal efforts, the schools serving the children remained in place” (Clapper 2006: 242). This pattern was already ingrained from as early as the 1905-1920 period (Kitzmiller & Rodriguez 2021: 3) but intensified after the Great Migration of Black communities from the south.

The problems of the postwar period sound the same as those from the 19th century: “Financially, there was little money available from state or federal governments for school construction, and Philadelphia, like most rustbelt cities, had begun a long slide into financial troubles” (Clapper 2006: 243). Except this time, the underinvestment came along with white flight and civil rights movement organizing. Pressure from community organizers like Floyd Logan and Sylvia Meek created consciousness and pressure around the situation. Meek, working with the Urban League, noted that there were 67 non fire-resistant elementary schools in 1964, many of which served predominantly Black populations. At that time, the district had to ask its citizens to vote for bond financing, a practice common throughout the country. These bond proposals failed more often than not in this period, leading to less revenue for capital outlay (Clapper 2006: 255).

While there was some new construction in Black areas, the effort was not a positive contribution to residents’ lives. “Schools were used to contain the Black population in specific neighborhoods/areas” (Clapper 2006: 257). Thus, “it became apparent that a different sort of education was to be offered” (Clapper 2006: 58). Historically, there has been a connection between facilities and race in the School District of Philadelphia. In the 1960s, the Philadelphia Urban League created a school desegregation plan via 20 educational parks in the city (Wilder, 1967b). They defined an educational park “as a complex of school facilities which includes all levels of grade organization… located on a single site and serve a population large enough to insure both integration of students and concentrated of resources necessary for quality education” (Wilder, 1967a). These educational parks never materialized due to local pushback (Peters, 1967b). Furthermore, while the Board of Education sought to build new schools funded by acquiring more loans for SDP, both the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission and Rev. Henry Nichols, one of the Black members of SDP’s Board of Education, urged voters not to support the Board increasing its debt because those school buildings in Black neighborhoods would be staffed with substitutes and would maintain racial segregation in the faculty (No Author, 1967; McCann, 1967).

School buildings across Philadelphia have been in constant need of repair. There were conditions so deplorable that one 1967 Philadelphia Tribune writer described them as “unfit for animals.” Some schools were so overcrowded that some students would eat lunch standing, and the adult men’s restroom in one school was converted to a classroom (Wilder, 1967c). Students at William Penn High School even protested conditions at their school, demanding a new building and carrying signs that proclaimed, “It’s a Shame to Go to School at William Penn” (Peters, 1967a). When the District’s former associate superintendent of facilities became the superintendent of schools in 1975, he sought to manage the extreme lack of resources that beleaguered the district (School District of Philadelphia Board of Education Minutes, November 25, 1968, p. 874). One of the ways he did this was by eliminating that facilities leadership position (School District of Philadelphia Board of Education Minutes, October 20, 1975, p. 776; November 24, 1975, p. 866).

There was a contradictory approach to the popular policy of busing at the time. “The geography of new school construction ensured the necessary of busing while simultaneously ensuring the political will to resist busing” (Clapper 2006: 259) Then, as the crises of the 1970s set in and civil rights efforts waned in the region, “between 1975 and 1997, the school district managed to build four new schools” (Clapper 2006: 260). Very few. The facilities crisis continued but in a new iteration into the present arrangement, which has inspired new generations of activists who bang on the deteriorating brick walls of their community schools calling for a change that never arrives. There are accounts of students focusing on facilities issues across the decades, like this study from 2001:

Members generally articulate and define the issues that frame and drive the local organizing campaigns. Issues come out of one-on-one meetings between the organizer and youth or parents, and broader listening campaigns that the organizer and core leaders may carry out with other youth or parents and school staff. School climate and facilities are often foremost in these discussions and tend to be the entry points into school reform organizing. "A lot of times when we start in a school, our first concern is a physical building concern. We've dealt with dirty water fountains and graffiti. Once the youth have won on this level we've been able to push them to look inside the school," says Rebecca Rathje, Coordinator of YUC. (Mediratta, Fruchter, Gross, Keller, & Bonilla 2001: 16)

For example, in the 1980s, disrepair of the school buildings that housed Potter Thomas and Hunter, both located in North Philly which primarily served poor Black and Brown children (SDP BOE Minutes, November 6, 1989, p. 961). This was a big concern for its state representatives, and the blight surrounding the schools was thought to combine with the state of the schools to encourage more drug activity. During the 1987-88 school year, SDP Superintendent Constance Clayton was greatly concerned with the issue of the district’s facilities. She told the Board of Education, “we face an awesome challenge in marshalling the resources and developing a comprehensive strategy to improve substantially the maintenance appearance and functional utility of school buildings and administrative offices…” (SDP BOE Minutes, January 11, 1988, pp. 2-7). While she was engaged in a facilities master planning process, this process was hampered by the game of chicken Clayton and City Council played over the budget (Royal, 2022; SDP BOE Minutes, May 31, 1988, p. 370).

Years later, when Paul Vallas was the CEO of Philly’s public schools, he and the School Reform Commission considered Durham School’s property and the Wanamaker School to need repairs so extensive that it made more sense to sell them than to repair them. However the Wanamaker building was not too damaged to house Hurricane Katrina survivors. And though Durham School’s sale price was $6 million, it was sold to a charter school for $1.1 million (Royal, 2022). The SRC also sold SDP’s headquarters in a package with other District buildings for $25 million, a lowball figure by many accounts. But the motives here weren’t just fiscal. The SRC sought to rebrand SDP with its new buildings (Royal, 2022).

References

Clapper, M. (2006). School design, site selection, and the political geography of race in postwar Philadelphia. Journal of Planning History, 5(3), 241-263.

Cutler, W. W. (1974). A Preliminary Look at the Schoolhouse: The Philadelphia Story, 1870-1920. Urban Education, 8(4), 381-399.

Kitzmiller, Erika, and Akira Drake Rodriguez. (2021). “Addressing Our Nation’s Toxic School Infrastructure in the Wake of COVID-19.” Educational Researcher, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 88–92.

Kitzmiller, Erika, and Akira Drake Rodriguez. (2022) “The Racialized History of Philadelphia’s Toxic Schools.” Metropole, Jan. 2022, https://themetropole.blog/2022/01/13/the-racialized-history-of-philadelphias-toxic-public-schools/.

Mediratta, K., Fruchter, N., Gross, B., Keller, C. D., & Bonilla, M. (2001). Community Organizing for School Reform in Philadelphia.

Royal, C. (2022). Not paved for us: Black educators and public school reform in Philadelphia. Harvard Education Press.

Thomas, G. E. (2006). From Our House to the “Big House”: Architectural Design as Visible Metaphor in the School Buildings of Philadelphia. Journal of Planning History, 5(3), 218-240.

School District of Philadelphia Board of Education Minutes, November 25, 1968, p. 874.

School District of Philadelphia Board of Education Minutes, October 20, 1975, p. 776.

School District of Philadelphia Board of Education Minutes, November 24, 1975, p. 866.