New Bond Issuance and the Problem of Capacity

I've heard through the grapevine that progressives in the city might be interested in campaigning for a big bond issuance to fix up Philadelphia's schools. This is great news and has caused something of a stir in the education movements, particularly for wonky lefties like me. I started digging around to get a sense of the terrain and see what I could find to be helpful.

What I've done thus far is get a feel for issues that the district might raise in response to such a proposal. The schools need around $5 billion of infrastructure updates. So why would they--specifically the finance people at the district--say no?

I've actually considered this question before. When I started this newsletter, I was organizing to get the district to apply for a loan from the Federal Reserve's pandemic-response program called the Municipal Liquidity Facility. I was proposing that the district issue a bond to the Fed for around $760 million, focusing on zero emissions fixes for HVAC and windows, and also demanding that the Fed change the terms of these loans (as an aside this is how I'd prefer to get money for capital projects as a socialist: a public source with no fees, zero interest, but this isn't looking likely in the short term).

While I was having conversations about this proposal I heard a similar refrain: the district doesn't have capacity for a loan that size. I bet this point will come up again during this new bond issuance campaign, so I looked into it more and found some interesting things.

Time is never time at all

'Capacity' in this sense means the district's ability to manage and complete a project of a certain dollar size. For instance, the district recently issued a green bond totaling $315 million with about $75 million of the proceeds going to construction projects that lower energy usage and emissions. But that's a drop in the bucket compared to the billions of dollars of work that needs to be done. Why not do more?

They give a few reasons. One of them is timing. They say that they can't plan, hire labor, acquire materials, and then complete enough of a larger project within the time constraints placed on municipal bonds by government regulation. I got curious about this in particular. It sounded legitimate and serious.

I was told that, according to the Internal Revenue Service, borrowers of tax-free bond monies has to spend a certain percentage of that money within a certain amount of time, or else. More specifically, I was told that the school district has to spend 85% of a bond issuance within two years of issuing it, or else the IRS can force the issuance to become taxable.

This is big if true. Two years is not a lot of time to spend $760 million! And the district, whose credit rating in 2018 was raised to just above junk for the first time since 1977, would not want to risk its loans becoming taxable. The only reason ruling class lenders invest in municipal bonds is because the interest payments they get from them are tax-free. They make a lot of money that way. If the loan were to suddenly become taxable then no lenders would be interested and thus, so the district says, threaten the credit rating.

The rule makes some sense. You wouldn't want someone taking out a huge loan and then sitting on the money for its whole timespan. One of the district people I was talking to said that Puerto Rico had done just that, something called arbitrage, and the IRS said enough is enough and passed the regulation.

But I'm always trying to learn about this whole mess called school finance. So I got curious. I wanted to read this IRS law for myself. What I found surprised me.

Living on the hedge

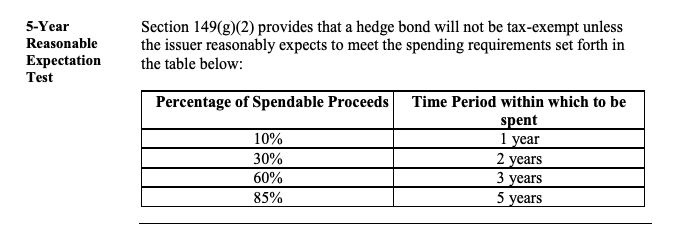

The IRS has helpful documents called Lessons, which appeals to me as a teacher. These lessons carefully articulate the apparatus's position on various questions in the tax code. Lesson 8 covers Section 149, or "Rules Applicable to All Tax-Exempt Bonds." In this lesson, laying out subsection (g) of section 149, there are two pages of information regarding time limits on tax-exempt bonds.

The two pages are in a part of the lesson about "hedge bonds," which they define as "bonds which are taxable bonds because they have failed to meet certain requirements regarding the investment and spending of proceeds." Basically, you don't want your municipal bond to become a hedge bond. You shouldn't try to game the system otherwise the IRS will make it taxable and pull the rug out from under you. Why don't they like this practice? The lesson tells us that

Prior to § 149(g), municipalities could issue bonds when interest rates were low, even though there was not an immediate need for financing. They were “hedging” against the risk that interest rates would increase in future years. Congress viewed this practice as a drain on the federal treasury because the bonds were outstanding longer than necessary. The hedge bond rules were enacted to ensure that bond issues were reasonably sized and timely issued.

Apparently, when municipalities hedge on interest rates this is a "drain on the federal treasury," taking out 'unreasonable' municipal bonds and not repaying them them in a 'timely' way. (I'll have to ask my MMT friends what they think about this.) In any case, there are two tests to determine if a bond is a hedge bond:

1. The issuer must reasonably expect to spend at least 85 percent of spendable proceeds for the governmental purposes of the issue within 3 years of the issuance date;

2. 50 percent or less of the proceeds are invested in non-purpose investments having a substantially guaranteed yield for four years or more.

You have to do both of these things to keep your bonds from becoming hedge bonds. If you don't reasonably expect to spend at least 85% of the proceeds for your stated purpose within three years and/or you invest more than half of the proceeds in stuff not having to do with your stated purposes for four or more years and make bank doing so, the IRS is going to turn its evil eye towards you.

Pausing here. Note that the school district people told me you have spend 85% in two years. It's actually not two years, but three years. That makes a difference, gives you a whole other year! Further, if we consider the context of this guidance it starts to become clearer that we shouldn't worry about it too much.

Not that reconciliation

At the beginning of the lesson, we find out that "§ 149(g) was added by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989." That's right, congress was still doing reconciliation packages then (a process from the 1970s). From what I can tell, the 1989 experience was not like today's reconciliation, which as of this writing is still up in the air.

In the fall of 1989, congress adjourned a month earlier than expected. In a "flurry" of activity, they passed this law. A bunch of stuff was in it, including the following under Subtitle F - Miscellaneous Provisions:

Part VI: Tax-Exempt Bond Provisions - Subjects to arbitrage rebate requirements certain tax-exempt bonds (hedge bonds) when certain percentages of the net proceeds are not spent by the end of each of five years from the date of issuance.

This brought the 149(g) guidance we just learned about into existence. Why?

Puerto Rico

I'm looking into a more concrete answer to this question, but I know it has something to do with corruption from the long history of Puerto Rico's debt crisis. From what I can gather, in 1917 the United States created a rather promiscuous "triple tax exemption" policy for the island's bond financing to encourage US capitalists to buy Puerto Rico's bonds. This promiscuity led to gobs of capitalist misdeeds and a mountainous debt crisis on the island, which came to a head recently and led to a federal oversight board called PROMESA.

One of those capitalist misdeeds was doing arbitrage on municipal bonds, basically using the proceeds of those bonds to invest in other stuff and not paying the money back. That kind of arbitrage was going on in the late 1980s in Puerto Rico and I guess the IRS got sick of it and got lawmakers outlaw it. Thus 149(g). Again, I want to do more research on this to find details but that's the overview.

Si se puede!

The upshot of all this is that the 149(g) guidance is not meant for apparatuses like the School District of Philadelphia. Maybe it'd be relevant if the district's finance directors were doing shady stuff--like maybe they were in earlier decades--or had a bad credit rating or had an unreliable flow of revenue. But Philly's not like that. The district has been 'right-sized' somewhat over the last recent period since 2012. There's been more regular borrowing and repayment. Also, property values have doubled here in the last 15 years. The district would stand up to an audit if the IRS had any questions. Finally, it's a school district! This isn't just any old municipal government. We're trying to educate kids here.

But even if a big bond issuance were deemed a hedge bond according to an IRS analysis, the guidance gets more flexible.

So you've got a full five years to spend 85% of the bonds if you're deemed a hedge bond without the bond being made taxable. This guidance should not be used as a talking point against a big bond issuance. We should be able to do it! We can do it! Don't let anyone say the IRS won't allow it.