MSPERS of War

I’m appearing on the amazing Have You Heard podcast later this week. The hosts asked me to look into a specific school district’s budget crisis. This time, it’s Ann Arbor, Michigan. And wow, there’s a lot going on here. This week I just want to get into some details that I haven’t seen analyzed elsewhere in the coverage of this crisis.

The district’s budget shortfall is $25 million. That’s really high in terms of district budget shortfalls, which I’ve been seeing mostly in the single digit millions. And if we consider some of the typical losses that districts are facing (enrollment drops, federal fiscal cliff) we see some of these in Ann Arbor: $1.4 million in state funding decreased, for instance, and an additional $3.4 million decrease in “overall district revenues,” which came, say reports, from an increase in hiring and a decrease in enrollment over the last nine years.

In Ann Arbor, things are a bit more pitched than elsewhere because, according to its own numbers, the district hired a bunch of people to “attract students” over the last ten years, but then covid hit and 1,000 students left, leaving this lurch. (See this reddit thread for a debate on why. Seems to me the commenter who talks about cost of living there has the right of it. Taxable property values have increased about 7% since 2019.)

But $5 million is just a drop in this bucket. Why is the budget crisis so intense? This particular part from recent reporting caught my eye: “Several factors contributed to the budget shortage, including $14 million in state support from last year’s budget that was misallocated to this year’s.” What? Misallocation of state support? What does that mean?

In March, a “financial consultant” named Marios Demetriou (about whom more in a moment) gave a presentation to the district’s board members (called trustees). It’s the spiciest, most intense school finance meeting I’ve seen in a long time. First, I want to get wonky and delve into this “misallocation” issue. Then I want to tell the political story I’ve gathered from reporting and talking to someone in the district.

Taketh-ing away

During the meeting, right at the beginning, Demetriou said the following:

we have we had in the budget an item that happened last year, um, it was for the unfunded accrued liability for retirement and, um, we get that every year but also last year there was also one time that came in and then it was, with the unfunded accrued liability…we get the money and then next payroll we send it back to the state on the revenue side…this one time item that happened last year was still in the budget so we are removing it, it's not happening this year so we're removing it.

What’s Demetriou talking about? The “unfunded accrued liability” for retirement refers to pensions, specifically “the difference between the estimated cost of future benefits and the assets that have been set aside to pay for those benefits.” This goes straight to the stuff I’ve written about a lot in the past: how contribution rates are calculated. Pensions provide defined benefits to retirees.

To pay out those benefits, they need income, which they get in the form of contributions from employers. In the case of teacher pensions, the employer is the school district. There’s a big debate over whether teacher pensions are in crisis, which I’ve written about here and elsewhere. This issue has now thrown Ann Arbor Schools into a generalized crisis.

According to Michigan’s teacher pension website:

Pension Unfunded Actuarial Accrued Liability (UAAL): This portion of the contribution rate is also determined each year by the retirement system's actuary and is charged as a percentage of payroll. The UAAL is the difference between the retirement system's assets and the pensions accrued (for past service) to current and future retirees. Each year, a payment is made against the UAAL reflecting the amortization payment and interest.

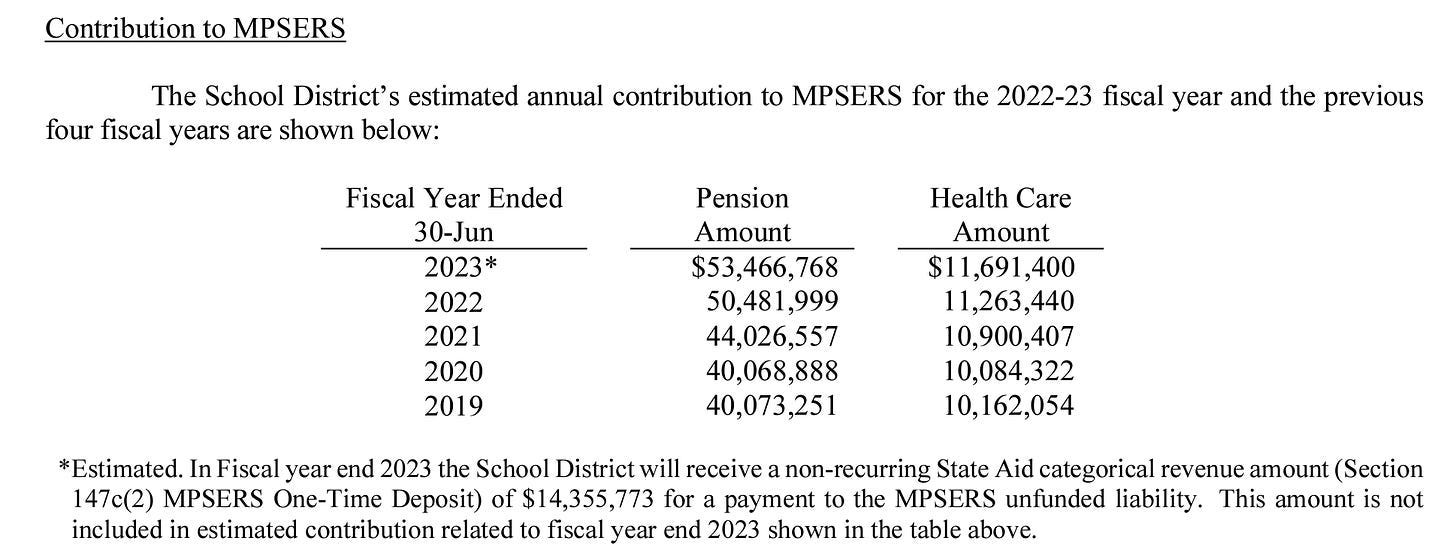

Michigan does this interesting thing where they pay school districts and municipalities a certain amount of money which the districts then have to pay back every year. There’s a cycle of giving and paying back. According to a 2023 bond statement: the district “will receive a non-recurring State Aid categorical revenue amount (Section 147c2 MPSERS One-Time Deposit) of X for a payment to the MPSERS funded liability.”

Again, the district has to pay this back at the end of the year. It’s how Michigan manages the pension’s unfunded liabilities, by giving and taketh-ing away. What’s interesting is that the taking is actually a giving in this case, since I’m pretty sure this is the state’s way of cost-sharing pension liabilities with its municipalities. Yet another postmodern public finance moment, it’s giving Derrida’s Counterfeit Money.

Giving-taking aside, Ann Arbor forgot to put this payment in both the revenue and expenditure sections, incurring a huge loss. (It’s cringe, but Reason put together some research on MPSERS, how it works, and some proposals to fix the issue. Meanwhile, the union also has its critique of the pension system, for which it’s currently sending around a petition to change. I’ll adjudicate this debate below.)

To really get into the weeds on this situation, we have to examine the teacher pension’s contribution rate calculations, which I’m starting to do but is extremely dense.

What I can see is that pension contributions increased by $13 million starting in 2019, a significant increase, adding to conservatives’ arguments about how teacher pensions are eating into school district budgets.

In any case, Trustees asked questions about this huge mistake, rightly calling the missing $14 million a “tremendous amount of money,” summarizing the problem and asking pointed questions:

Trustee 1: for this year's budget they put in the $14 million expecting us to get it [on the revenue side], which is a presumption, number one, but why wouldn't it also be in the expenditure side if it's always gone back?

Demetriou: I cannot answer the question why, I wasn't here.

Trustee 1: It's just an enormous amount given the numbers…

Demetriou: I'm trying to correct whatever is…um I'm trying to tell you the truth [about what] is happening but…

Trustee 2: So that 14 million was on one side, but not the other?

Demetriou: Correct.

Trustee 1: I'm right to assume it gave us a distorted view of what our budget and our fund balance.

To repeat, the budget office, in putting together their budget request for this year, had to figure out what was coming in and what was going out. How did this mistake happen? Demetriou is part of the story. He’s maybe the assistant superintendent for budget and finance now? Or just a consultant? I’m seeing reports he’s been hired back but also can’t get confirmation. But he actually retired from this same job in 2020. He’d served the district for a long time—he was known as a “ninja of finance”— and there was a new superintendent coming in.

Here’s where the story is. (Incidentally, I made a tiktok about this which kind of blew up!)

Swifties

I think the podcast is going to get into this in more detail. But from what I can tell after chatting with someone from the district, the previous Superintendent, Jeanice Swift, was forced out after a bitter period of tension with the district. This bitterness came to a head when a school bus aide attacked a student with autism. The episode was apparently the last straw for many who blamed Swift’s approach to special education. The board is nothing if not embattled, with trustees resigning from bullying, for example, and disagreements about spending over the last five years.

Amidst a worsening budget situation, the board also struggled with passing a ceasefire resolution, the controversy around which made national headlines.

The community was divided around Swift, with the teachers union actually coming out against her immediate removal, asking for due process. Two trustees on the board, who also happen to make up the finance committee, are strong Swift supporters. In any case, district officials made the accrued liability mistake amidst all this turmoil, on top of an already-worsening budget situation that the whole country is facing (more on which below).

Eventually, interim superintendent Jazz Parks was brought in to lead the district. She brought Demetriou back after the departure of Executive Director Jill Minnick, who had replaced David Martrell. Parks needed the finance ninja to sort things out.

And, well, he’s doing that. Demetriou discovered the huge shortfall when he looked through the books, leading Parks to alert the district to the financial crisis at hand. And here we are.

I’m told that the district is waiting for an independent financial consultant to come in to talk about next steps. But approximately 60 teachers have already been laid off and, at the budget meeting, Demetriou said that 94 staff in total may have to be fired to cover this shortfall, since 80% of the district’s expenses are labor costs.

Headwinds

When we get into deeper numbers for the district, we can see certain fluctuations that I think show this situation to be fluid. There are questions we can ask. Some things are structural and harder to change, but other things might be more flexible.

Audited financials 2022-2023 mention increasing costs due to inflation. Remember when the Evergiven got stuck, the pandemic shut down supply chains, and then war broke out in Russia, messing with oil prices? That has an impact. We shouldn’t forget this landscape of global capitalism, which decreased the district’s fund balance by around $7 million.

Another feature of American capitalism adversely impacting this district: our awful private credit regime. There were downgrades in AAPS credit rating in 2021 and 2023. In 2021, this is what Moody’s said:

The rating also considers the district's high leverage including liabilities related to exposure to a poorly funded statewide cost-sharing pension plan and increasing bonded debt as the district issues the remaining $860 million in voter-approved bonds over several years to finance significant capital improvements.

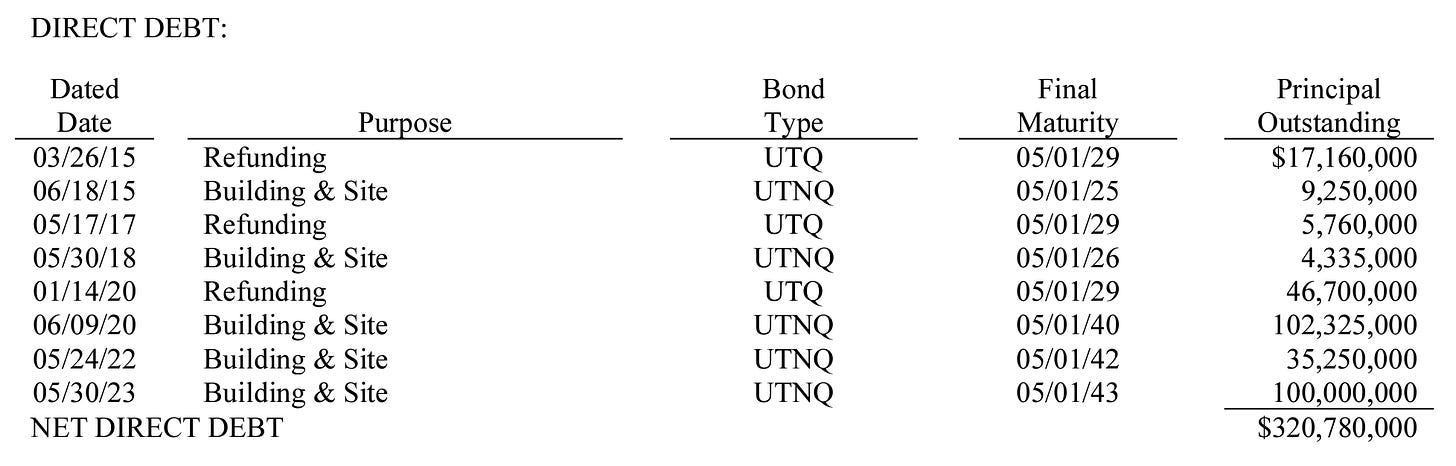

We’ll get into the statewide cost-sharing thing below. But let’s look at the increase in bonded debt: there was a big bond taken out in 2019, right before the pandemic. A bunch of districts in this area and probably all over the country issued big bonds right around this time, which has really messed them up. In 2023, debt service was 7% of the district’s budget. That’s around where school districts tend to be in the US, but there was a big jump recently that probably joslted the district.

Debt has jumped up and up. In 2018, principal outstanding on direct debt was 4.3 million. By 2020 it’s 102 million. This is because the district needed to maintain its facilities.

In our new paper, Camika Royal and I argue that the bond market is a toxic financing regime, and this is another reason why we need a national infrastructure bank in this country, along with creative pension policy. There are some other structural features to consider here too.

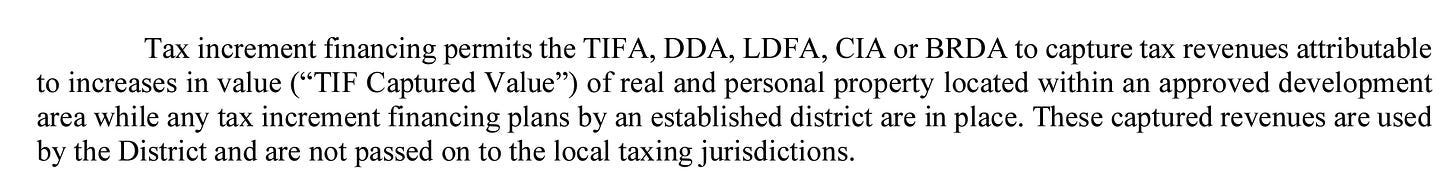

There is a tax increment financing scheme for downtown Ann Arbor, and I wonder how much revenue that’s siphoned away since 2018.

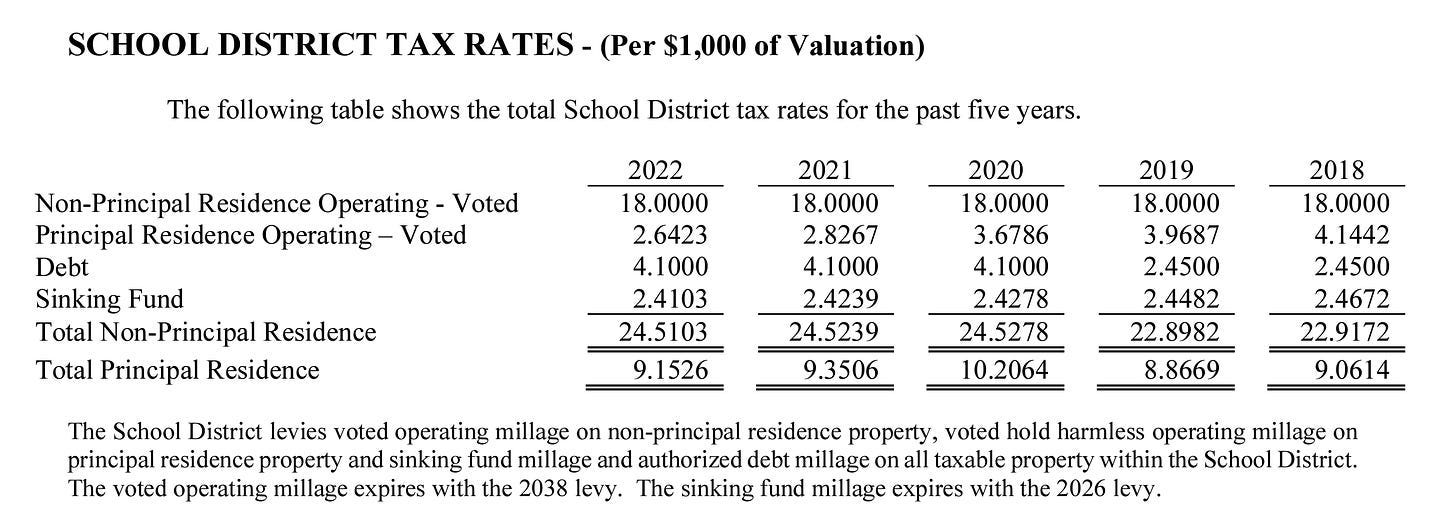

Finally, I’m interested in Michigan’s “Headlee Amendment,” which sounds like a kind of local austerity policy that forces municipalities to decrease their mill rates.

We can see fluctuations in Ann Arbor’s taxation over this period of the new bond, with debt mill rate increasing from 2.45 to 4.1 and principal resident rate decreasing from 4.1 to 2.6 from 2018. Between 2020 and 2022 at least, the mills went down a tenth. The question isn’t whether the local revenue is decreasing absolutely, but whether it’s decreasing relatively. They could be getting more than they are, but is this Headlee amendment is preventing that? It is called a “constitutional millage rollback,” which probably plays the same role as Massachussetts’s Prop 2.5. It’s forced austerity, but it’s an unforced error that’s a remnant of 1970s tax revolts. Why shouldn’t the municipality be able to raise its taxes more?

The MSPERS of War

A good chunk of this crisis comes down to pension policy. The one-time recurring deposit to pay for the UAAL, if the union is to be believed, is sort of a good thing. Before 2012, the districts were totally responsible for paying down the extent to which the pension wasn’t funding itself according to contribute rate calculations (which, again, are done through discount rates that are in fact a political technology, as Lilia Doganova writes, and we should look at them carefully—for another time).

But then in 2012, the state put in place a cost-sharing policy where the state will cover any unfunded liabilities over 20.96% above a district’s payroll. That means the district doesn’t have to pay for any unfunded liabilities above that threshold. The union agrees with this policy since it takes districts off the hook. I’m wondering whether that Sec147c2 payment is calculated using that threshold. If it this, then it’s this policy that generated the conditions for AAPS’s huge budget hole, since they forgot to pay the state back for its help with the UAAL.

Parenthetically, the union thinks that there’s an extra $670 million in state coffers for public education, since the state is on track to over-fund its UAAL for OPEB (this is healthcare for retirees), which is on track to paid down.

Then we have the libertarians. They’re claiming that MSPERS has $29 billion in unfunded liability. First, I wonder where they’re getting that number. They’re probably being twoers about this, assuming really low market returns to make the defined benefit system look bad. That’s my guess.

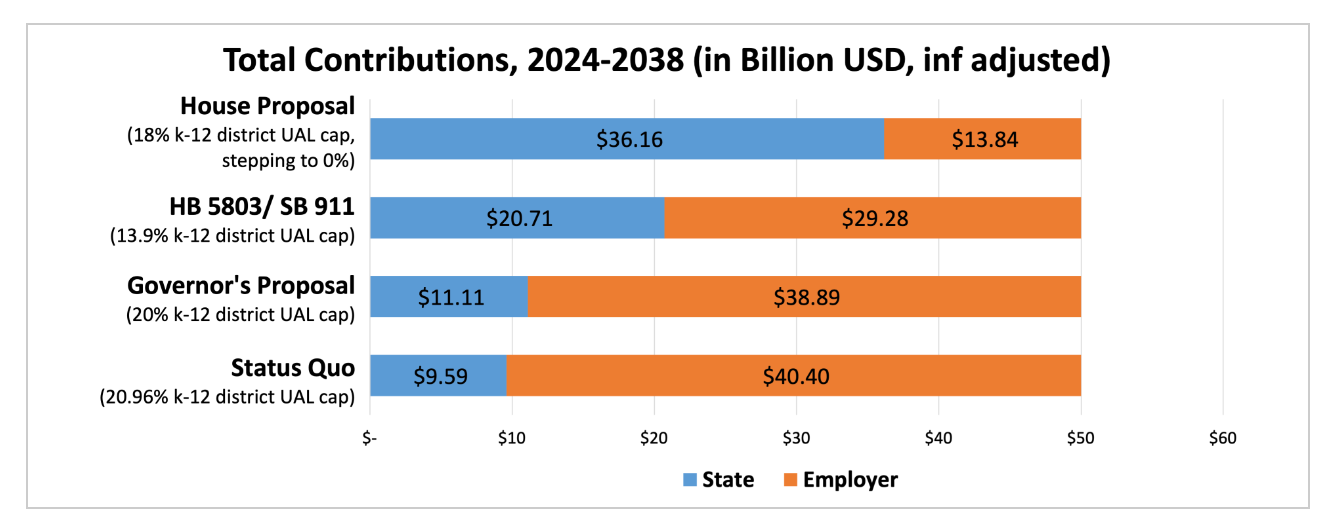

But they’re doing some interesting work to assess different proposals coming up from the Governor, Senate, and House. Each proposal messes with the caps. For districts, the House proposal is the best. But my second question is how they’re calculating this numbers for projecting out the costs. There are presumptions they’re making, but how?

The union and the libertarians are fighting at different points in the landscape. But it’s interesting to note that there’s a situation that benefits public school districts the most: the House proposal for pension UAAL caps with a redistribution of UAAL OPEB funds rather than over-funding it. What I don’t know is whether/how the state government will finance the increased pension payments, and whether that’ll have a negative effect on districts in other ways.