Mortifying amortization

Leonie Haimson slightly corrected a previous post of mine. She’s a prolific NYC-DOE watcher so I was grateful for her feedback. I said in a previous post that the city’s department of education is “just that, a department of the city government.” But she rightly points out that that’s not quite right. She tells me:

Actually, the DOE is considered rather a state agency than a city agency; only the state can make laws when it comes to policies to be enacted in our public schools – though the Panel for Education Policies (legally still the Board of Ed) also must approve a certain limited list of policies enacted by the Chancellor.

Consequently, the City Council only can pass laws that deal with DOE reporting requirements, not laws regarding policy unlike any other city agency. The Mayor achieved control over our schools via a temporary state law in 2002, which has been renewed every two or three years -- it did not make the DOE a city agency per se.

The same goes, she says, for the School Construction Authority (SCA): city agencies that are sort of state agencies. The thing about the SCA is that it’s it’s own agency that oversees the DOE’s capital budget but, also, it’s sort of also a state agency. Agencies in agencies.

I start this week’s post with her clarification, because when it comes to the DOE’s debt service (my focus today), there’s something similar at play. I wrote about the DOE’s debt two weeks ago, but it was sort of buried at the end of an already complex post, so I wanted to write about it again and go slower with it.

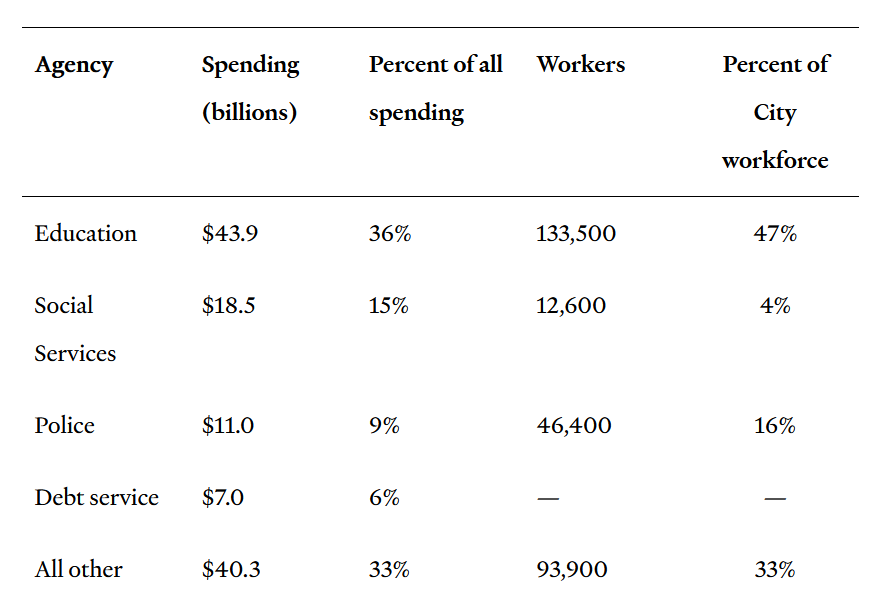

In Andrew Perry’s piece on Mamdani’s first budget, it’s notable that debt service is the fourth largest category of NYC:

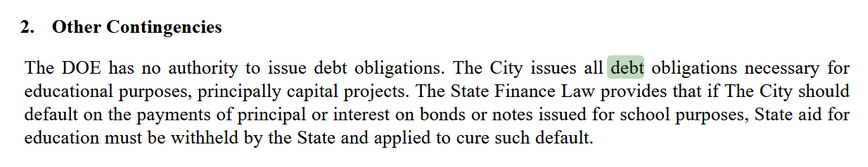

That’s for the city. As a recent building aid revenue bond statement says, the DOE can’t issue its own debt.

The DOE’s debt is a creature of the city. But the city’s debt-incurring power (which is less than half used up), as I mentioned last week, is a creature of the state.

Here we have a great example of relative autonomy. Each entity—DOE, city, state—has some effectivity (agency/room to maneuver), but those effectivities are indexed to one another such that the agencies of the agencies limit, constitute, and grate/grind against one another.

Thinking about where the effectivities are, how they’re indexed, and the degrees of freedom operators have within each entity is basically how one can wield state power.

For instance, Politico, which apparently loves to do How’s The Socialist Gonna Pay For It pieces about education, recently published this one about class sizes. While most of the actual piece is about construction, the lede says:

Within months of being sworn in as mayor, Mamdani will have to steer public schools toward a critical deadline: 80 percent of classrooms have to meet the class size limits by next September. The state law — signed by Gov. Kathy Hochul in 2022 — requires the city to reduce all classes to between 20 and 25 students, depending on the grade, by September 2028. The school system has projected up to $1.7 billion in costs for teacher salaries and $18 billion in school construction costs.

But again, we know that the DOE is itself a relatively autonomous entity whose budget is financed through the city and state. Furthermore, school construction is overseen by the SCA, a relatively autonomous entity from the relatively autonomous DOE, whose budget is financed through debt incurred by the city but then reimbursed by the state.

Not only is there room to maneuver for financing this stuff in NYC, the rules don’t apply the way Politico implies.

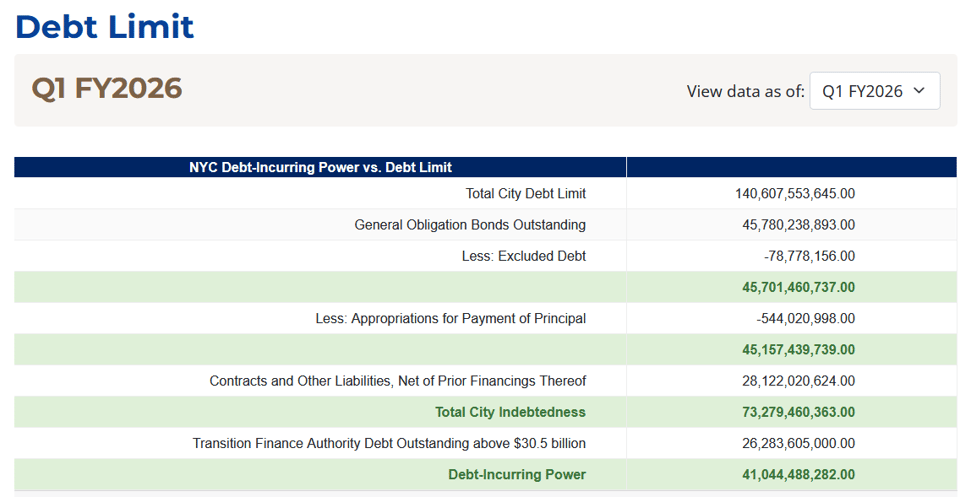

The comptroller’s report lays this out pretty clearly. The city’s debt-incurring power is $44.4 billion, with an ever-increasing debt limit.

So Mamdani’s well within those limits and has runway to work with for getting his agenda off the ground. But here’s the thing, when it comes to education—which is a different category of capital outlay—these debt limits don’t even apply!

School construction in NYC is financed with building aid revenue bonds (BARBs) which the Citizen’s Budget Commission confirms is not subject to state debt limits (see footnote 7). So the city can sell some BARBS through the TFA, not worry about state debt limits, and get reimbursed by the state for it.

This doesn’t mean there’s nothing to worry about when it comes to the DOE’s debt in NYC.

DOEbt

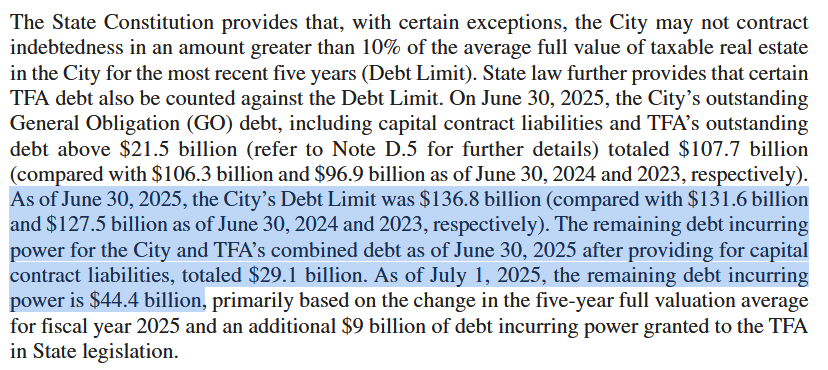

If you want to know the DOE’s debt obligations, it’s a little tough to get details about. Their budget website has is a single number that’s a bit dated at this point.

We can see here that the district is reporting $3.4 billion in debt payments. This happens to be the same amount spent on charter schools (which means that if we didn’t have charter schools all the district’s debt’s could be paid off for the year, ugh).

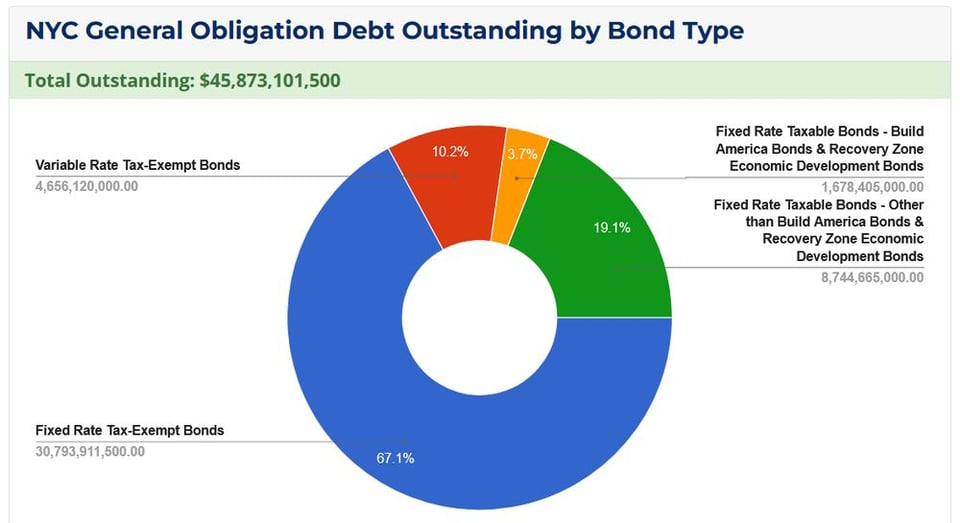

But what’s in that number? There’s very little in the DOE’s budget documents that breaks this down. We know it’s not just the city’s number, because the city has $45.8 billion in debt outstanding.

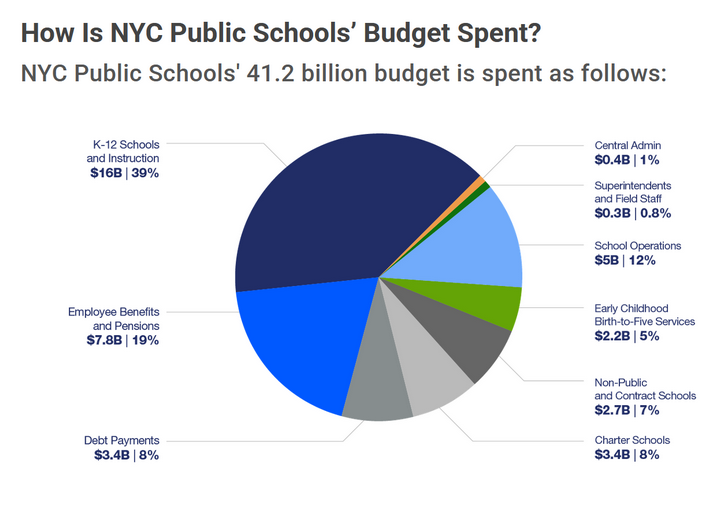

There’s also a fun graphic that tracks the city’s debt incurring power, which I mentioned above:

The debt limit for the whole city is $140 billion and it’s only at about a third of that in GO bonds, about half when all’s counted up. There’s still more than $40 billion worth of room to breathe.

But, again, what about education, which is a different category of outlay?

This is where I got tripped up. The comptroller’s report doesn’t break down the NYC public school debt numbers, another indication of how the DOE isn’t quite the city department I’d said it was.

The DOE’s audited financial statements only went through 2024. They haven’t updated those documents along with the comptroller. Nothing in EMMA was showing exactly how these debts broke down. I was so frustrated!

Then I finally found a document that had it. I couldn’t even tell you how I found it. I just like to click around and sometimes I do it so randomly I can’t retrace my steps. I found something called a Financial Status Report. The DOE puts these out six times a year, and the most recent one was from September. Yahtzee!

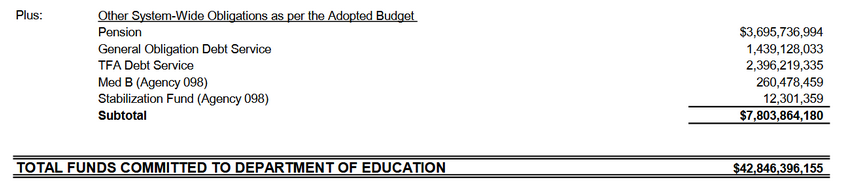

There under the expenditures was a breakdown of the most recent debt numbers in a section below all the other funds committed for the DOE, with a neat little “Plus:” designation.

Here you can see that that the DOE is responsible for $1.439 billion of general obligation debt service along with $2.396 billion in TFA debt service.

The latter is the Transitional Finance Authority debt, composed of both building aid revenue bonds and future tax-secured bonds. (Now I’d love to break these numbers out but I didn’t get that far. To break the TFA debt down we’d have to go back to the bond statements, which I can do in the future. But to break down the general obligation bond debt, phew, I’m not even sure. That’s a question for the future.)

In any case, as of September 2025, the DOE has $3.835 billion in debt obligations. That’s a nearly $400 million increase from the pie chart. How’d that increase happen? And what will that increase look like as Mamdani takes office?

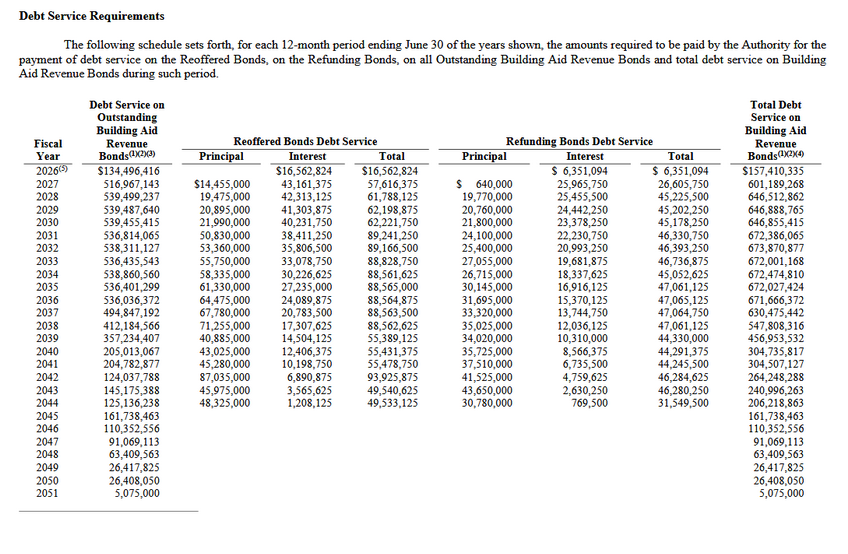

But that’s not what raised my eyebrows. The last thing I want to show you is an amortization table from a recent building aid revenue bond document posted by the TFA. It shows the schedule of paying down some of this debt. I found something a little concerning.

Mortifying amortization?

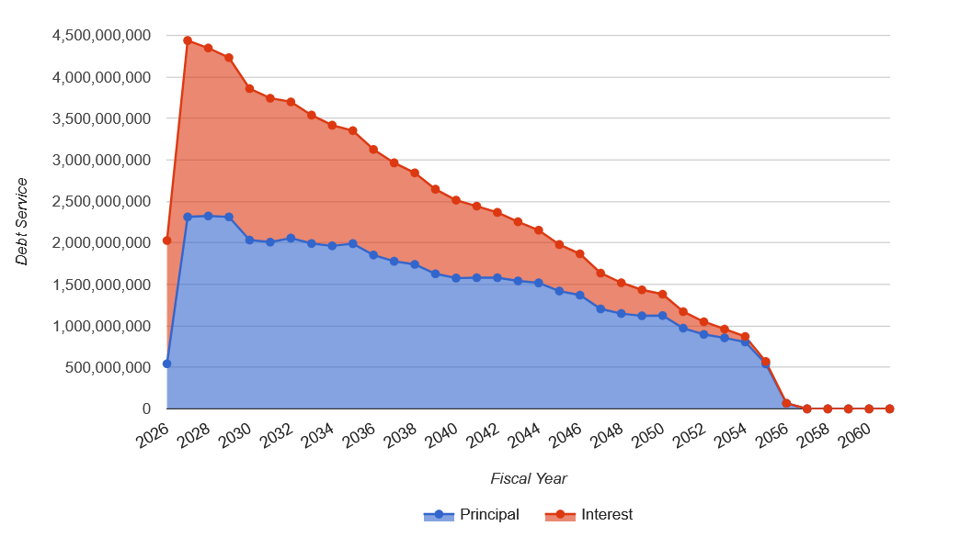

Here we have a payment schedule where the DOE will be repaying its building aid revenue bond debt (the sort of debt it takes out from the TFA). You can see in 2026 that the service on these BARBs is $157.4 million. Check out what happens by 2027: it jumps up nearly $450 million to $601 million. Then in 2028 it jumps again to $646 million.

In the first two years of Mamdani’s administration, whoever he picks to be the Chancellor, will see a dramatic increase in debt responsibility for BARBs, a doubling.

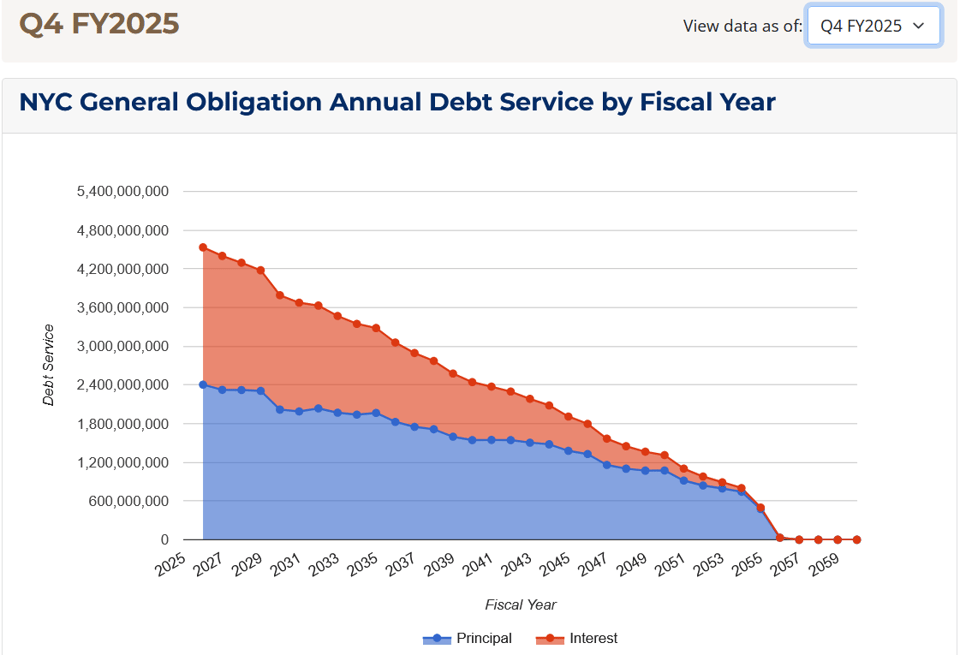

The payments are coming due. And this mortifying amortization tracks the overall jump in NYC’s debt obligations, depicted by this comptroller graph.

You can see that doubling. I think this happens because a certain amount of 2026’s debt is sort of paid off for the purposes of these reports, like a proration maybe, so come 2028 you see a big jump? These numbers are in the Q1 2026 debt profile. When we look at the Q4 2025 we don’t see that same jump.

First, look at all that interest it has to pay! Damn! Second, what’s happening here? Perry notes a practice called “surplus roll” where “the City dispenses its surplus by prepaying subsequent year expenses… In fiscal year 2025, for instance, the City accrued a $3.8 billion surplus. It booked this as 2025 spending in the form of prepaying spending liabilities in fiscal year 2026.”

So maybe Adams did a surplus roll for 2026 and these debt payments will jump up? Whatever the explanation, they’re going to jump. Furthermore, Jonathan Liu notes in the Politico piece that the Adams administration did very little with school construction this past year, which I’ve seen in the SCA’s report: they’re dangerously under their targets for meeting class size requirements.

All this gives you a fine-grained sense of what the Mamdani administration’s DOE will actually be dealing with in terms of its debt and construction needs. It looks to me like the debt service will jump up dramatically due to a possible surplus roll by the Adams admin, combined with that administration’s lackluster work on school construction. As it stands, Mamdani will have to pay more in debt service to get less progressive on class size.