Liberatory municipal finance

Important reading: The Labor Network for Solidarity and Building Power Resource Center have published an awesome new report that everyone should read called “Bargaining for Green Schools, Good Jobs, and Bright Futures.” The research is top-notch and, as someone told me recently, it’s the best way to fight fascism right now.

***

Announcement: After working with the press on the promotion of my new book As Public as Possible, they gave me a discount code for readers of this newsletter.

If you pre-order the book now, you can use the code TNP30 to get a discount.

Meanwhile, I’ve got some book event dates set up. Here are the dates and places so far:

12/3 @ 7pm - HUUB, Orange, New Jersey

12/10 @ 6:30pm - Skylight Room, CUNY Grad Center, New York City, co-release with Celine Su

1/12 @ TBD - School for Advanced Studies in Social Sciences (EHESS), Paris, France, with Nora Nafaa

If you want me to come do a talk, either online or in person, with your group/office/chapter/whatever, I’m happy to set it up. Just respond to this email. More dates to come!

Now to this week’s post:

***

I’ve developed protocols to see what’s happening with school finance regimes to generate questions, critiques, and horizons for organizing.

But I haven’t articulated what the approach here is called, pedagogically. As a former teacher and philosopher of education I think that’s important to do! So that’s what I’m writing about this week.

I think of my approach as ignorant municipal finance, following French philosopher Jacques Ranciere’s thinking in The Ignorant Schoolmaster, a philosophical biography of 19th century pedagogue Joseph Jacotot and exhumation of his unique teaching style that assumes the equality of intelligence.

Here’s what means. While there might be inequalities of knowledge, time, and resources, there is no inequality of intelligence among humans, that is, everyone can encounter things, think about them, and make meaning from them in some fashion. When you assume the equality of intelligence, everything looks different.

I often begin trainings with a story of when I experimented with this radical hypothesis myself.

During Occupy Wall Street, I worked with a number of activists on pedagogies appropriate for the movement (we held a weekly open workshop at Trump Tower’s private public space, Thursday nights). One night we discussed Ranciere’s ignorant approach to teaching. A friend of mine, who was a doctoral student in medieval Italian, was skeptical.

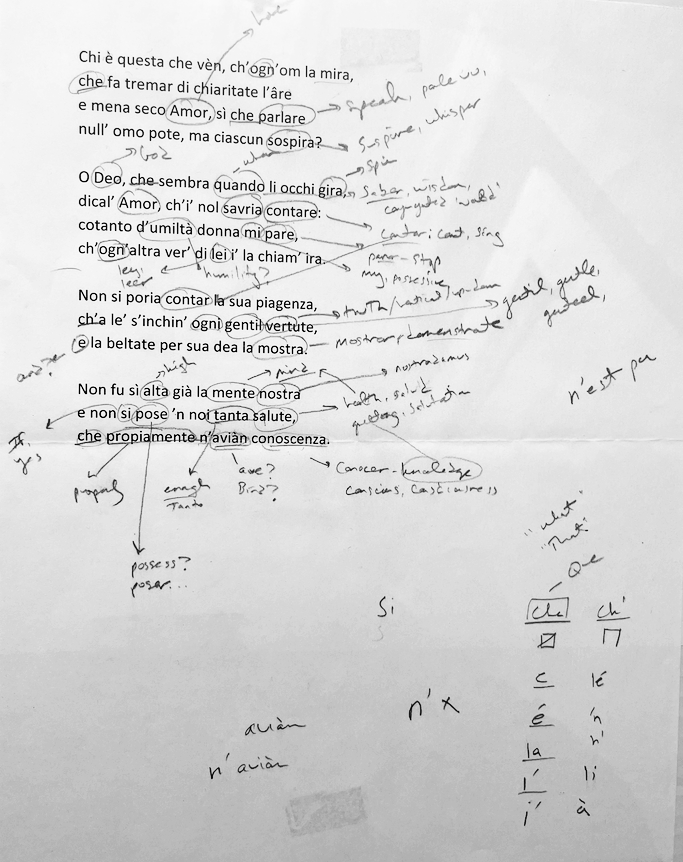

Later that week we got lunch and the subject came up: how could someone who doesn’t know anything about a complex topic have equal intelligence about that topic to someone who does know a lot? I said that Ranciere claimed we had to assume this equality as a hypothesis and then test it over and over again, so I asked my friend: are you working on any medieval Italian poems right now? He said yes. I said, give me a copy of one and then let me look it over for fifteen minutes and let’s see what happens. He produced a copy from his bag.

I didn’t know anything about medieval Italian poetry. But I took the paper and started noticing things. I saw certain words and letters that reminded me of other words that I do know.

I noticed grammatical marks, dashed and apostrophes and accent marks, and made a diagram tracking all of them. I circled the words I thought I recognized from Latin roots and guessed their meanings in the margins, tracking also different potential forms of grammar: what I thought were verbs, prepositions, nouns. I used these clues to think through what possible themes of the poem might be, including god, love, soul, etc.

After fifteen minutes I had a bunch of observations, questions, and notes. I turned the paper to my friend and said: can I ask you some questions? He looked at me a little surprised, but then seeing my notes he said wow, you don’t have these things all correct but you’re well on your way.

I have that poem framed in my office.

The lesson here for municipal finance is crucial: everyone can encounter finance documents, think things about them, and then make something of them. I’ve been doing it for years now so I recognize some things and have facility with bond documents, audited financial statements, and legislative language. But it’s really just doing this equality of intelligence thing over and over again.

These are the texts that govern the flows of resources to our communities and we are all intelligent enough to look at them and begin to make meaning of them. Ignorance is just the starting position, after which we can read the documents, think about them, and then make something of what we find together.

Ranciere says this is a liberatory pedagogy, challenging the stultifying and oppressive assumptions about the inequality of intelligence. This liberation is especially powerful in public finance.

Campbell Jones wrote that the world of finance is parasitic on the world of us, and that we have to make incursions into the world of finance to get the social world more in tune with our world. The ignorant approach to municipal finance takes a sledgehammer to the wall between the world of finance and us, opening up possibilities to challenge it.

Another important insight here is one about numbers. Perhaps we’re not math people and encountering numbers gives us a feeling of fear or repulsion. This is the result of oppressive math education but also some unexamined premises in critical approaches to quantity.

Desrossiere, in the Politics of Big Numbers, notes that numbers both reflect reality and rely on conventions to do so. Those conventions are subject to ideology just like any natural language with which we might be more comfortable. It’s just a matter of seeing the numbers as discourse as well, with their own powers and ideologies and poetry.

These numbers are subject to and determine struggle in profound ways and we need not fear them, even if we were taught otherwise. Those of us more prone to the theoretical and theatrical than the quantitative should not see a dichotomy here, as statisticians as far back as the 1600s were aware: numbers come with categories.

Just like we bring the dialectic to bear on novels and films and current events we can bring it to bear methodologically on the numbers and policies of municipal finance.

My protocols assume the equality of intelligence, the conventionality of numbers, and the need for dialectical categories, but proceed in concrete steps:

1) Map the municipality in terms of property value, race, segregation, and climate vulnerabilities.

2) Find reporting and discourse about the exact points of contention in municipal finance: news reporting, YouTube recordings of budget committee hearings or meetings, and Reddit threads about the municipality and finance. Triangulate nodes of interest in the conjuncture of the budget crisis.

3) Search the Electronic Municipal Market Access for issuers and issuance, audited financial statements, and event-based disclosures. Then bring the nodes found in (2) to these documents, using control F.

We trace the big increases and decreases of numbers in tables, noting definitions and policies and histories contained in these documents. These become the basis for questions at city council meetings, board hearings, and bird dogging.

They become the talking points of campaigns and social media posts, even slogans. They become the fodder for transformative imaginative policies that take on the structures getting in our way. In so doing we begin to confront the regimes that stand between our movements, electeds, and the world we fight for.