How to do critical school finance

I'm giving a guest lecture at the University of Manitoba, Canada thi week. The title of the lecture is "How to do Critical School Finance." The professor who invited me is teaching a course on education policy and law, reviewing difference approaches to this subject. Since I've been writing this newsletter, my research has gone in this general direction: applying the tradition of critical consciousness to school finance.

In the presentation, I'm going to make the general point that traditional approaches to school finance are more technical, technocratic, and aloof, focusing on the esoteric details of this realm of public policy and finance in relative isolation from the political-economic contexts in which it is implemented and changed. Being critical about school finance means following Max Horkheimer's lucid description of critical theory in his essay "Traditional vs. Critical Theory":

The aim of this activity [critical theory] is not simply to eliminate one or other abuse, for it regards such abuses as necessarily connected with the way in which the social structure is organized. Although it itself emerges from the social structure, its purpose is not, either in its conscious intention or in its objective significance, the better functioning of any element in the structure. On the contrary, it is suspicious of the very categories of better, useful, appropriate, productive, and valuable, as these are understood in the present order, and refuse to take them as nonscientific presuppositions about which one can do nothing.

In general, Horkheimer says that “[a] critical theory of society…is, a theory dominated at every turn by a concern for reasonable conditions of life.” So we have to be suspicious of the categories of better, useful, appropriate, etc., as they're understood in the present order, the way society--namely production--is organized (by which he means capitalism).

What happens when you apply this lens to school finance? I think a couple things. First, you switch from a technical to a political-economic framework that zooms out on the larger social context of school finance and then zooms in on the struggle between social groups within that context. More specifically, it means applying Lenin's imperative to always ask cui prodest? or: who stands to gain from the present order?

In my presentation I'll give a few examples with which readers of this newsletter will be familiar: the case of Philadelphia's toxic school buildings, the toxic regime of financing behind this crumbling infrastructure amid the polycrisis of climate, racial, gender, ability, migrant and other crises. But I'll give these examples to show how to use this method generally.

I thought I'd stop there, but then I thought to myself "you can't just talk about Philly, what about the students' own context?" So then I started doing a whole cui prodest workup on the University of Manitoba. Here are some things I found:

In March of this year, the UM student newspaper reported on recent increases to the university's budget, the provincial government adding $169 million, including a 2.75% tuition increase cap. The article primarily quoted representatives of the student union, which I favor when doing CSF in this case, because students are a population whom the university must serve but typically don't have much say in processes of university financing. I'm curious about student struggles. We can contrast their perspective, for instance, with the university's own triumphalist announcement.

The student union reps were largely positive about the increase, particularly the tuition cap, but remained critical in a few ways. They don't think this slight increase will undo seven years underfunding the institution (this was also the faculty union's position, which the student paper quote early on, good solidarity). Students are also disappointed that the university hasn't included international students in its healthcare plans, leaving these students on their own to take care of their medical needs, as well as difficulties accessing financial aid systems.

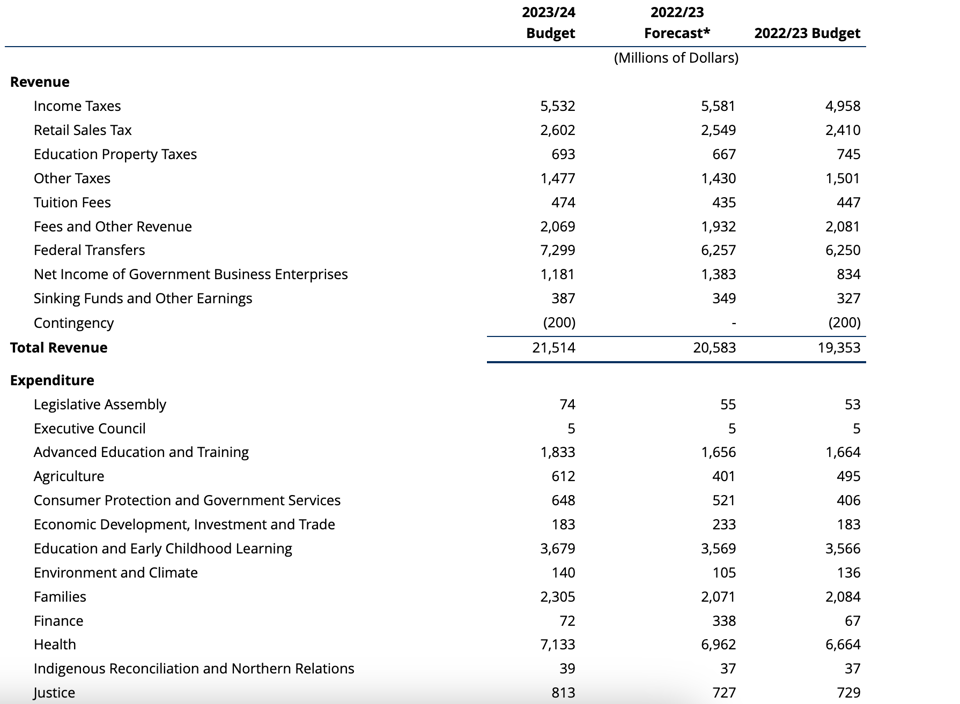

I got curious about a few things in this situation. I have no idea how higher education finance works in the Manitoba province, so I looked up the most recent provincial budget.

Looking at these numbers, I like to watch what's going up and what's going down and by how much. The university's announcement named the Advanced Education and Training line of the budget as being the higher education expenditure. You can see it going up there by about 10%, which isn't nothing. In terms of why, we learn that:

Minister of Advanced Education and Training Sarah Guillemard acknowledged that labour shortages were a factor in increasing funding for post-secondary institutions.

Guillemard projected that the province will need to fill 114,000 jobs within the next five years and that 60 per cent will require post-secondary education.

So there are labor shortages in the province, leading to increases in higher education finance. I wonder why there might be labor shortages? According to an opinion piece in the local news site Troy Media,

In 2022, over 22,000 people moved from Manitoba to another province, an increase of 42 percent compared to 2021. Recently there have been job shortages reported all over the province. Doctors Manitoba recently released a report highlighting that the province has the lowest number of family doctors per capita in Canada. The group also says that two in five doctors are planning to retire, leave, or reduce their clinic hours within the next three years. The Winnipeg Regional Health Authority says there is a 20 percent vacancy rate for home-care workers. Winnipeg is having trouble finding lifeguards and arena attendants, with some pools having to cut back on hours.

Seems like a problem!

But I was also wondering where this increase might be coming from on the revenue side. When we look up to the top of the chart it looks like income tax revenue has actually gone down (is that related to the labor shortage? fewer people, fewer taxes...), while other taxes and fees have gone up a little (I wonder how the education property tax works, eg). Nothing major. But it looks like the federal grants have gone up more than the others, relatively speaking. So Canada is chipping in more to the Manitoba budget. I wondered what the story might be there? Some things are changing in Manitoba politically for sure: an NDP candidate just got elected as Premier there.

The last thread I wanted to follow was regarding the actual flows of revenue from the Manitoba province to the university. I know that it's rarely the case that money just simply arrives in the accounts of government apparatuses. Typically, governments borrow to get the revenues they need up front and then pay back those loans on regular cycles. I wondered how Manitoba's borrowing and repayment regime works, and found the province's debt management and strategy page, laying out some details. They tell us:

To ensure market availability to complete its borrowing program, Manitoba raises funds in both domestic and international capital markets. The domestic market is the primary source for the province for both short- and long-term funding. Manitoba has a well-established short-term borrowing program. This provides the Manitoba government with a cost-effective source of financing while also providing liquidity. These financings are primarily raised through the weekly 91-day Treasury-Bill auction.

Okay, so most of the financing is done through Canadian Treasury bill sales. Basically the federal government is lending directly to the provincial government on this 91-day schedule. But that's just domestic. I wonder what "international capital markets" the Manitoba government borrows in? Which industries or countries does the province get their credit from? They say "the province has formal programs filed with the regulators in the United States, Europe and Australia." So creditors in these places, along with the Bank of Canada, benefit from the province's borrowing, which will most likely increase due to their increase in expenditures on higher education. As people leave the province, Manitoba spends more money on higher education to train more people to fill the vacant jobs, which means more borrowing and interest payments to domestic and international creditors.

It made me wonder about the relationship between international students' healthcare and international creditors--who's getting the better deal here?

And on and on. There are all kinds of threads to follow. I'm hoping students might find stories or documents from their own school contexts to start to ask these questions with one another as an example of how to do critical school finance.