"First Person Shooter"

Before I get to today’s post, an announcement: If you’re in the NYC area, consider attending this amazing event on Green Schools and Labor put on by a bunch of amazing folks that I work with:

United for Green Schools: Labor, Communities & Cities Leading Change in the Face of Disinvestment

Date: Monday, 9/22

Time: 10:30am-12:00pm ET

Location: The Center for Fiction auditorium (15 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11217)

RSVP link: Register here, please.

Notes: Doors open at 10:00am. Light refreshments will be served.

***

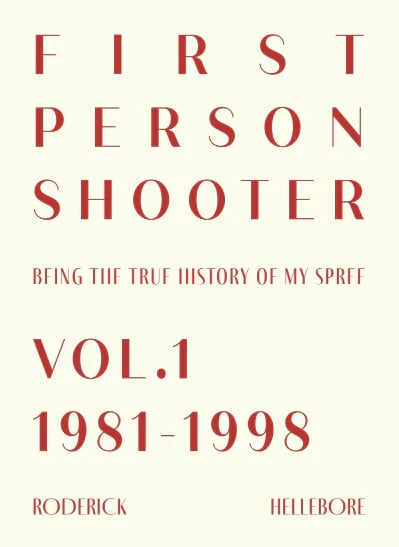

A friend sent me a novel called First Person Shooter: Being the True History of My Spree, Volume 1: 1981-1998. My friend wasn’t the author—it was someone I’d never heard of, called Roderick Hellebore. I hadn’t heard of the press either: Todos Contentos Y Yo Tambien, out of New York City and Valencia, Spain. Apparently, my friend said, the press had been started just to publish this novel. They said I might be interested in it.

I checked it out and I certainly was. I’ve been looking for a book like this, but I didn’t know such a text was possible. Hellebore’s book is poetic in the rawest sense: a bringing into being of that which hadn’t been, a new speaking of the unspeakable, a working-through of the present ideogemically in a ‘novel’ way, both in the literary and newness sense of the term.

The very grammar, semantics, syntax, and structure of the text makes the unsayable sayable and the unthinkable thinkable, the whole thing standing as a kind of awful monument to our moment, this moment, in the United States, that others try to name but haven’t quite accomplished.

I’m writing about the book here because it’s about mass shootings, and so much of the story is about education, school, the implosion of social reproduction; and so it’s about the meaning of the mass shooting, including the school shooting; executed in ways that few have been able to pull off.

The school shooting is a centerpiece of our educational reality, one which many remark briefly upon at their outbreak and then forget, disappearing it from view, pushing to the unconscious because of its unspeakability: how could this happen? Who would do this? Why, for god’s sake? Hellebore’s book is an answer to those questions that socialists and everyone else interested in education and a better society should engage with.

I came by my interest in school shootings somewhat intimately. My seventh grade math teacher’s wife was the principal at Sandy Hook elementary school, in Newtown, Connecticut, the site of the one of more gruesome school shootings in history. That hit home for me back then.

Then after the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas I steeled myself and told myself I’d sit with school shootings, think about them and write about them, because they mean something very important and we can’t just look away. I found ample reporting, some books, but nothing quite metaphysical enough to condense the essence of the situation, diving in and then stepping back and naming in a way that philosophers or literary authors might do.

I wrote an essay about the subject with a colleague, and after pitching it to a major leftist venue, the editors expressed interest. Inexplicably, they ghosted us on it after they’d expressed excitement about the draft. Literally they stopped answering our emails, never saying yes or no thank you, as though they also needed to look away and leave it all unsaid.

The novel forces us to look in a curative, cathartic fashion—much better than what I’d attempted, and quite creatively so. Methodologically, Hellebore made himself into a humanistic large language model, taking in a massive amount publicly reported text from mass shootings, starting, he says, at the year of his own birth, 1981, and then given himself a kind of prompt to re-render the documents and reporting into a literary narrative of ten mass shootings, each with its own chapter, told from the perspective of the shooter, each chapter written in the first person. The effect is eerie, rigorous, and path-breaking from what I can tell.

Like Hemingway, Octavia Butler, and Dan Simmons rolled into one, Hellebore constructs an all-seeing I that is “the shooter” reincarnating over and over (I was also reminded of Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Year of Salt), a violent presence stochastically manifesting throughout the unseen places of this country, the everyday places, the humdrum towns and burned out cities and rural districts where the people who don’t live in the major cities have their being.

This shooter-subject, a ghastly ghostly I, reconstructs each shooting in crisp detail for the reader, leaving no word un-smithed (be warned—it’s hard to read), producing a bracing, eventuating representation of the truth of the shooting. We see the fullness of the character of the shooters, each unique shooter gelling into a single metaphysical Shooter through a particularist retelling of life story, alongside the lifeworlds of their victims, the shooters themselves immanently melting into the more transcendental Shooter, showing us both the concrete details and their abstract similarities via the winding, sad, tragic, or pitiful paths they take towards the Terror they become. While this sounds complex, the sentences are alarmingly simple, almost seductively spaced out and easy to read.

In the process, we get a social novel of the American 1980s and 1990s: the Cold War, the gun culture, the alienation, the go-go successes and alienation, sexism, racism, exploitation, ableism, the smug and smarmy pop culture of those days, the music and the franchise restaurants and the highways, the ontology of flowering neoliberalism. We see it all through the sharp and distorted mirror of the “metempsychotic” Shooter subjectivity Hellebore constructs through each chapter.

The Shooter thus appears like Simmons’s horrifying Shrike on the scene: a creature from eternity traveling in and out of flowing linear time to murder ruthlessly and at random, an incomprehensible revenge from the unknown future on the past in the name of a forever-present soaked in blood and senselessness no expert or research or policy can name. It’s American Psycho but in a portrait that is both true and truer than the reality.

There are risks in the text; it toes and perhaps transgresses several fine lines. The fine line of found language, for example: whose words are these? Where does Hellebore’s re-rendering begin and where do the source documents end? Whose voices are we hearing? I wondered this while reading and I found it a little distracting to constantly be guessing about the provenance of the voice. There’s also a fine line of retraumatization: to what extent do these stories retraumatize us and those involved—proximately or distally— by Hellebore’s crisp and unnervingly engaging retelling, and thus what’s at stake in this retelling? Is it doing harm (or might it even be read as perversely celebrating these acts)?

In both cases, I think Hellebore pulls it off. There’s a clear statement at the front of the book about how dramatically the text was re-rendered, assuaging us about the voice. I also think that, while the violence is gratuitous, the retelling of it isn’t: the prose is spare where it could be more detailed, which is a humane choice, and there’s a clear valence throughout the text viz. the shootings: this is not something to celebrate. The reader is given space both in the narration and on the page to breathe through the difficulty and necessity of the prose. But the business is risky nonetheless and I could see some readers wonder and even feel concern about these risks and whether Hellebore does in fact pull it off.

I read the book in the days after Charlie Kirk was shot and, that same day, a white supremacist 16 year old shot up his own high school. It’s old hat at this point for us and still we haven’t come to grips with it. Well, please read this book and talk about it with friends and family. Assign it for your social work and education policy classes. Write about it. Hellebore has done us a favor, at great cost to himself, I imagine. Being in the Chinese room with these signifiers and churning out these texts must come with its own kind of trauma. But like all good art, especially literature, it provides us with something to work through our moment with towards a kind of healing and, hopefully, transformation.

As a coda, Hellebore includes an author’s note at the end laying out his process, signing off from Plymouth, Massachusetts, which, for all I know, could be a fiction as well, Plymouth being one of the ancestral places where the first violent and extremist white settlers landed in this territory and began their wild and dispossessive project whose name is ‘America,’ fighting against a Satan they thought was an external threat but ultimately was a force of their own unconscious, one that that they embodied like a call coming from inside the house, a devil-force Hellebore projects into a specular Big Other, producing a portrait of a face of our culture and country in terrifying and terrific detail that few others have had the stomach to attempt.