Don't be mean, Bloomfield Hills!

I’ve been getting a lot of awesome feedback and comments on my work looking into district budget crises by request on tiktok. This week I’m looking at Bloomfield Hills School District in Michigan.

The commenter asked me particularly about paraprofessional pay, which she said is the “worst in the county even though we’re the richest.” Searching around, I couldn’t find any reporting on this issue. I did find an old petition that the Michigan Education Association (MEA) put out a couple months ago that members supported. I can’t see breakdowns of para pay, but the MEA has a page for their paras caucus here.

Why wouldn’t Bloomfield Hills pay their paras well? We could assume a few things, like that paras are typically diverse working class folks, mostly women of color, and maybe the district leadership are being kinda racial-capitalist about para pay. The commenter implied this when she said that the district leadership told someone “we have no money to give extra money to people who tie shoes and make copies.”

There’s certainly a racial capitalism of paraprofessionals in education and this kind of language could be an interpellation of that structure. Bloomfield Hills district is 75% white and has only 3.8% poverty.

But let’s get into some numbers. Why would a school leader say something like that, materially? What kind of numbers might be underlying this charged language and the compel the MEA to pressure Bloomfield Hills to pay their paras more? And what could community members and union ask about to get para pay up?

Seems fine?

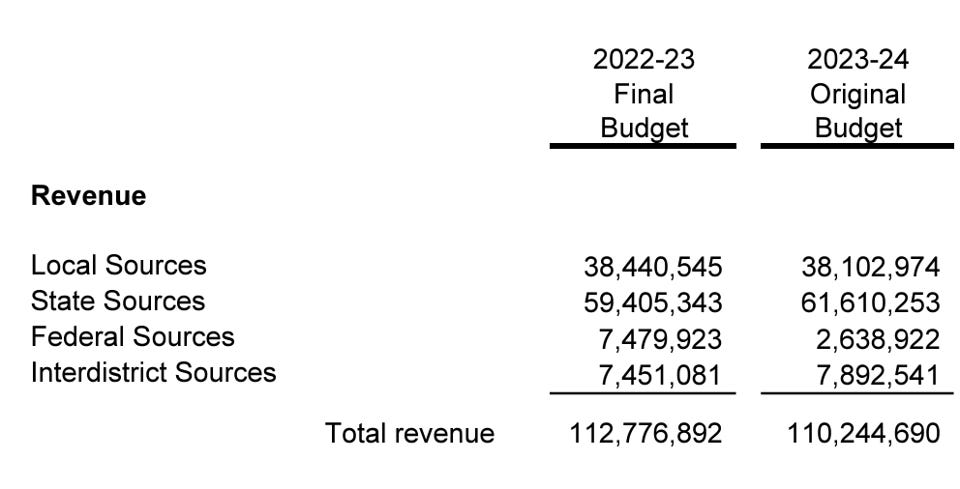

So when I look at the numbers, things seem more or less fine. Here are the budget documents I’m working with (sent to me by my contact on tiktok), which show the following:

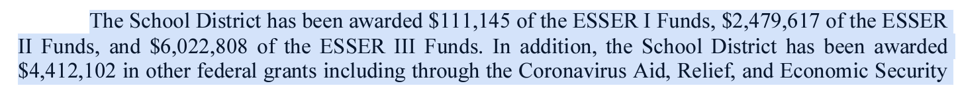

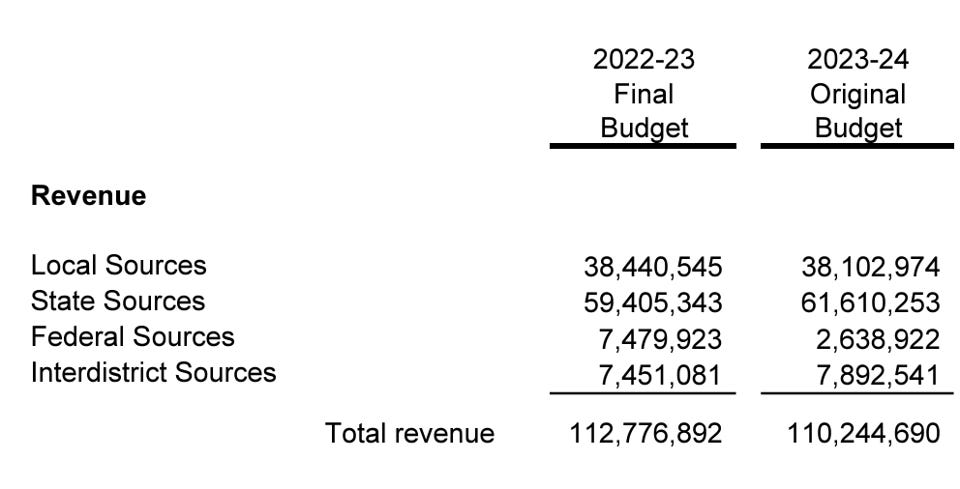

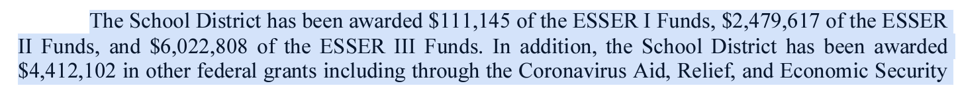

The audited financial statements I’m seeing show a $5 million decrease in federal funds, which is the fiscal cliff so many districts are facing. This district did get the most ESSER funds last year, in addition to other federal grants that are going to dry up.

So yeah, they’re headed for a tiny fiscal cliff to the tune of $2 million, but it’s not that big. When I look at their budgets everything seems sort of fine, which is one response to the district who says they don’t have money. They’re actually doing okay. There’s a slight decrease in local sources of revenue, sure, but both of those drops (local, federal) are sort of made up by an increase in state money.

So what’s the issue here? I think there’s more stuff happening beneath the surface.

Holding harmful

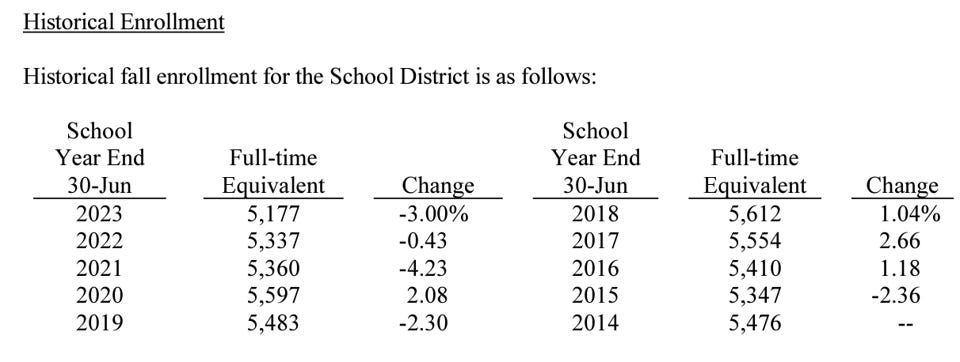

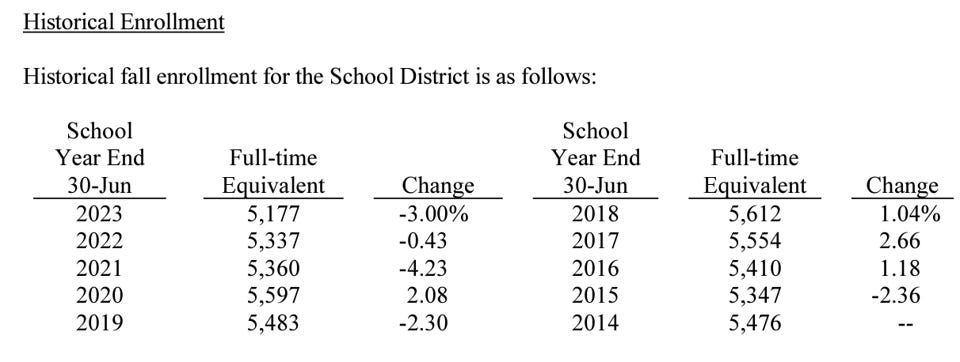

The district’s trends aren’t looking great. Enrollment is dropping: it’s gone down almost 8% over the last three years.

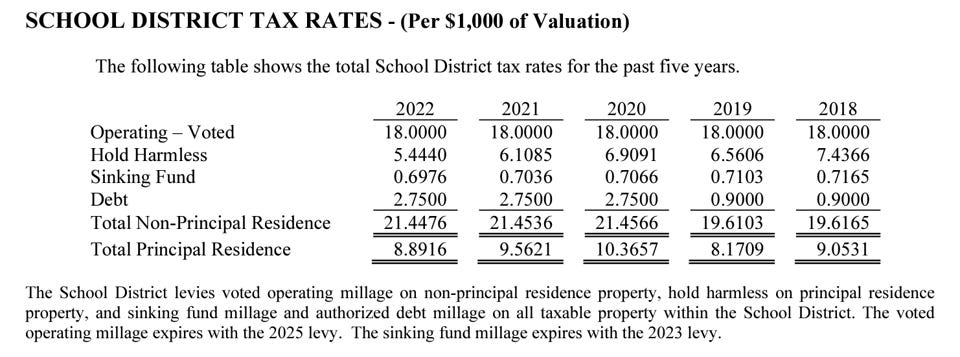

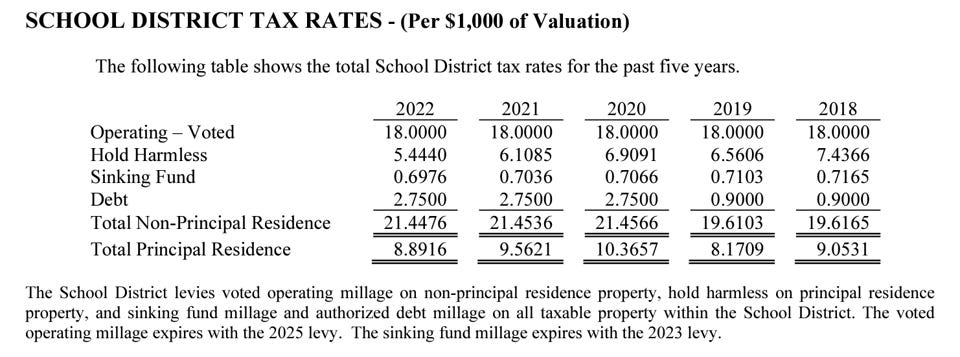

As the enrollment drops, there are some unpropitious fluctuations in tax rates. The tax rate on local revenues held harmless from year to year has decreased pretty significantly between 2018 until now. It was 7.436 in 2018 but by 2022 it had fallen 5.4. It dropped by about third!

Something I don’t understand is whether/how the hold harmless rate is controlled by the district. On the one hand, it seems to me that the state or some other entity would control a hold harmless rate, which then might shift depending on enrollments. But on the other hand, we see the hold harmless tax rate stays the same between years when there are drops. Why did that hold harmless rate drop in 2022 but not in 2021, for instance? And what is it now?

Also, the district’s tax rate for debt went up during that period, starting at .9 mills and jumping up to 2.75. The tax rates for grant revenue to the district are going down while the tax rate for debt is increasing. That’s creating a pressure on district leaders. Let’s look at the debt.

Taking it out

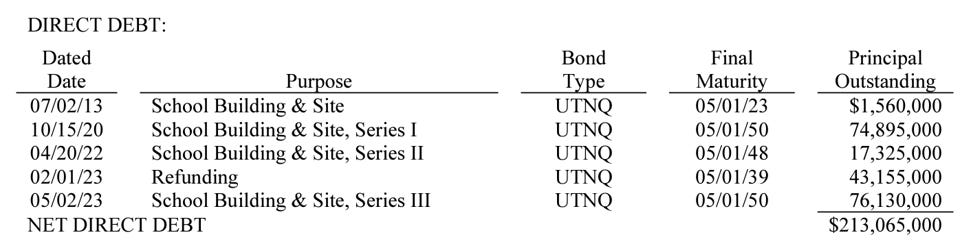

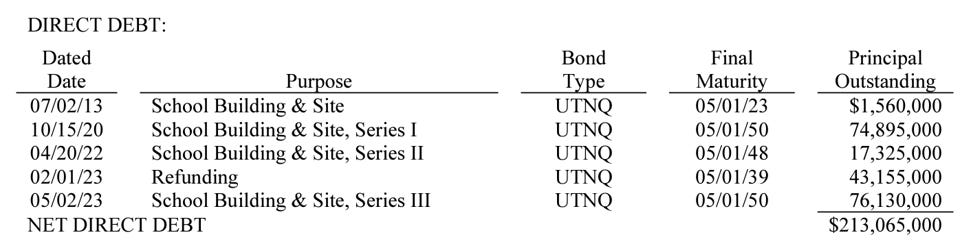

Some answers come when we look at the debt load that the district is taking on. Debt has arguably exploded since the pandemic. In 2013 the district had $1.56 million in principal outstanding. Then the district decided to take on a sequence of relatively large debts: $74 million in 2020, $17 million, $43 million, and then $76 million over the next three years. This all adds up to $213 million of debt.

When we look at the purpose of the bonds, it looks like the same as in 2013, “School Building & Site” but in three series upwards of $150 million if we don’t count refunding bonds.

People in Bloomfield Hills would know better, but this big bond project was undertaken in 2020 to work on the district’s infrastructure. The list from the bond document itself is below. It’s a lot of stuff, including fixing the pool. Also note their plan to build a new transportation center for new school buses.

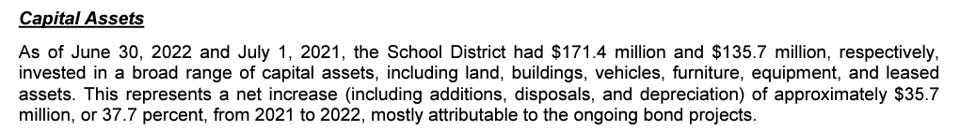

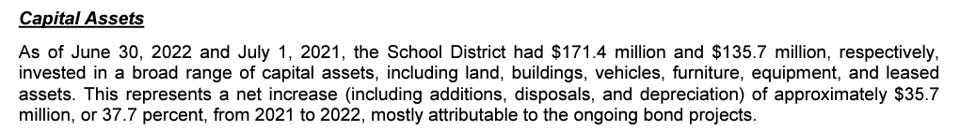

Audited financials from 2022 from Plante Moran (I guess that’s a known Michigan entity, since Ann Arbor is using them) tell us that capital projects went up by 37.7%, a big jump!

I’ve been getting a lot of awesome feedback and comments on my work looking into district budget crises by request on tiktok. This week I’m looking at Bloomfield Hills School District in Michigan.

The commenter asked me particularly about paraprofessional pay, which she said is the “worst in the county even though we’re the richest.” Searching around, I couldn’t find any reporting on this issue. I did find an old petition that the Michigan Education Association (MEA) put out a couple months ago that members supported. I can’t see breakdowns of para pay, but the MEA has a page for their paras caucus here.

Why wouldn’t Bloomfield Hills pay their paras well? We could assume a few things, like that paras are typically diverse working class folks, mostly women of color, and maybe the district leadership are being kinda racial-capitalist about para pay. The commenter implied this when she said that the district leadership told someone “we have no money to give extra money to people who tie shoes and make copies.”

There’s certainly a racial capitalism of paraprofessionals in education and this kind of language could be an interpellation of that structure. Bloomfield Hills district is 75% white and has only 3.8% poverty.

But let’s get into some numbers. Why would a school leader say something like that, materially? What kind of numbers might be underlying this charged language and the compel the MEA to pressure Bloomfield Hills to pay their paras more? And what could community members and union ask about to get para pay up?

Seems fine?

So when I look at the numbers, things seem more or less fine. Here are the budget documents I’m working with (sent to me by my contact on tiktok), which show the following:

The audited financial statements I’m seeing show a $5 million decrease in federal funds, which is the fiscal cliff so many districts are facing. This district did get the most ESSER funds last year, in addition to other federal grants that are going to dry up.

So yeah, they’re headed for a tiny fiscal cliff to the tune of $2 million, but it’s not that big. When I look at their budgets everything seems sort of fine, which is one response to the district who says they don’t have money. They’re actually doing okay. There’s a slight decrease in local sources of revenue, sure, but both of those drops (local, federal) are sort of made up by an increase in state money.

So what’s the issue here? I think there’s more stuff happening beneath the surface.

Holding harmful

The district’s trends aren’t looking great. Enrollment is dropping: it’s gone down almost 8% over the last three years.

As the enrollment drops, there are some unpropitious fluctuations in tax rates. The tax rate on local revenues held harmless from year to year has decreased pretty significantly between 2018 until now. It was 7.436 in 2018 but by 2022 it had fallen 5.4. It dropped by about third!

Something I don’t understand is whether/how the hold harmless rate is controlled by the district. On the one hand, it seems to me that the state or some other entity would control a hold harmless rate, which then might shift depending on enrollments. But on the other hand, we see the hold harmless tax rate stays the same between years when there are drops. Why did that hold harmless rate drop in 2022 but not in 2021, for instance? And what is it now?

Also, the district’s tax rate for debt went up during that period, starting at .9 mills and jumping up to 2.75. The tax rates for grant revenue to the district are going down while the tax rate for debt is increasing. That’s creating a pressure on district leaders. Let’s look at the debt.

Taking it out

Some answers come when we look at the debt load that the district is taking on. Debt has arguably exploded since the pandemic. In 2013 the district had $1.56 million in principal outstanding. Then the district decided to take on a sequence of relatively large debts: $74 million in 2020, $17 million, $43 million, and then $76 million over the next three years. This all adds up to $213 million of debt.

When we look at the purpose of the bonds, it looks like the same as in 2013, “School Building & Site” but in three series upwards of $150 million if we don’t count refunding bonds.

People in Bloomfield Hills would know better, but this big bond project was undertaken in 2020 to work on the district’s infrastructure. The list from the bond document itself is below. It’s a lot of stuff, including fixing the pool. Also note their plan to build a new transportation center for new school buses.

Audited financials from 2022 from Plante Moran (I guess that’s a known Michigan entity, since Ann Arbor is using them) tell us that capital projects went up by 37.7%, a big jump!

If I had to guess, given the trends they’re seeing nationally and in their own numbers, they’re feeling a little tense about (regretting? right-sizing?) the big bond project they took on in 2020, which was most likely put together way before that since capital projects take a long time to plan.

I’m thinking this because of a defeasance note I’m seeing from last year on $46 million of bond debt, where they’re calling the bonds, probably trying to get a better interest rate on them and save money.

Bottom-line: I’d be asking about the drop in that hold harmless tax rate. Is the district saying it doesn’t have money because they bit off more than they could chew in the 2020 bond issuance, while they decrease tax rates in ways that hurt them? Also, don’t take it out on paras and say mean stuff if you’re feeling pressure about your poorly-timed debt obligations! Could you keep the hold harmless rate up and give some raises?

Overall, this is a great example for why we need a national investment authority with a national infrastructure bank. School district leaders shouldn’t be getting tense about the debt they take out to work on their facilities and then taking it out on paras. Public finance for public infrastructure would fix this.

If I had to guess, given the trends they’re seeing nationally and in their own numbers, they’re feeling a little tense about (regretting? right-sizing?) the big bond project they took on in 2020, which was most likely put together way before that since capital projects take a long time to plan.

I’m thinking this because of a defeasance note I’m seeing from last year on $46 million of bond debt, where they’re calling the bonds, probably trying to get a better interest rate on them and save money.

Bottom-line: I’d be asking about the drop in that hold harmless tax rate. Is the district saying it doesn’t have money because they bit off more than they could chew in the 2020 bond issuance, while they decrease tax rates in ways that hurt them? Also, don’t take it out on paras and say mean stuff if you’re feeling pressure about your poorly-timed debt obligations! Could you keep the hold harmless rate up and give some raises?

Overall, this is a great example for why we need a national investment authority with a national infrastructure bank. School district leaders shouldn’t be getting tense about the debt they take out to work on their facilities and then taking it out on paras. Public finance for public infrastructure would fix this.