Capping in Seattle, or: b(ii) brute?

I’ve gotten a number of messages from separate people in Seattle about the budget crisis there. After chatting with them and doing some digging, I learned something interesting about the state of Washington’s special education funding policy.

For context, the Seattle Public Schools’ superintendent says there’ll be a $40 million shortfall in the 2025-2026 school year, on top of a significant shortfall this past year (as he reiterates at 1:05 of this public meeting recording), citing the usual stuff: declining enrollments, expiration of federal funds, and space under-utilization. The district went from proposing the closure of around 20 schools to closing just five, and recently has set up a committee to take a more participatory approach to the situation. But they’re threatening to continue the closures over the next few years if more money doesn’t come in.

Beneath these crises usually lurk more peculiar, occult, and problematic policy trends that the district doesn’t include in their narrative, either because it’s inconvenient or it’s not part of their messaging, or it may be just too confusing. A person involved in the budget fight there told me about one such policy that they don’t understand: the state’s special education funding multiplier, known more colloquially as the special education cap. I didn’t know anything about it before so I took a look, and wow.

State government as private insurance

Here’s an analogy to go into this wonky stuff thinking about: private health insurance. You know how private health insurance companies set up a game of rates, thresholds, and limits? Like, your out-of-network out-of-pocket and your deductible limit how much of your expensive care gets covered, and then, on top of all that, you have to submit your claims to be approved, etc?

These numbers and magnitudes and policies seem complex, but ultimately they tell a very simple story: the insurance company doesn’t want to cover you. They want to pay out as little as possible. It’s bad for business to be paying out on claims, so they try not to, and the way they launder their profit-driven stinginess is by applying this swarm of technical-sounding policies to justify their ultimate goal of not covering healthcare costs.

That’s sort of what’s happening with Washington state’s special education multiplier policy, specifically for a grant called the State General Apportionment for special education. Seattle Public Schools, located in a city with a lot of advanced treatment options for children’s health needs, could be getting, by my calculation, $71 million more dollars for students receiving special education services on top of a larger budget crisis situation. But the state doesn’t want to pay, and they use a policy called the b(ii) limitation to justify not paying.

Multipliers and dividers

Here’s the special education multiplier law. Districts get more money for special education programs because they’re more resource intensive. The state government calculates how much more money the district will get. How do they calculate this “excess cost”? After bracketing the 3-5 year olds who aren’t in kindergarten yet, they use a few numbers to come up with how much money they’ll give school districts. It’s a lot of counting and multiplying. And then dividing.

First, they figure out how many students in the district need special education services. They call that number the “annual average enrollment” of disabled students in the district. They multiply that by the “base allocation” for a full-time equivalent student, a base state grant.

They then multiply that by the “special education cost multiplier rate,” which varies according to whether students receiving special education services are in the general education setting for more than 80% of the time (1.12 rate) or less than 80% of the time (1.06 rate).

Pausing, I’m wondering how the district evaluates students to decide whether they put them into the general education program or not? Is there any disproportionality there? If there’s a disproportionate number of students less than 80%, you get less money, for example, but it could be racism if the students are disproportionately of color.

Okay, here’s the kicker, these multiplier rate numbers are subject to a limitation, which the law calls (b)ii, the cap of the special education cap. Here’s where the dividing comes in.

If you’ve got a reported number of disabled students above 15% or so, like if you report more than that total number of disabled students (no matter how many are in the gen ed program), then the amount of money you get has to be adjusted. Yikes. How do they adjust it? The calculation figured out at the rates previously mentioned have to be multiplied by .16 and divided by whatever your enrollment percent is. The exact wording is “must be adjusted by multiplying the allocation by 16 percent divided by the enrollment percent.”

So basically you can’t have too many disabled students. If you have more than 16% of your total enrollment, you get adjusted down relative to that number. The state doesn’t want to pay. Looking at the 24-25 budget, here’s how it actually works.

Coulda been $71 million

In the budget, there are two numbers for state special education spending. There’s the “special education excess cost adjustment” in item 4121, which is a bigger number and includes all kinds of things, and then the “general apportionment” number in item 3121, a smaller number. Combined, these make up the K-21 special education monies from the state. So we have to look at those. This is tough stuff and I’m not sure I’m getting all of it, but here’s what I’ve been able to gather. I took screen shots so you could share in the fun.

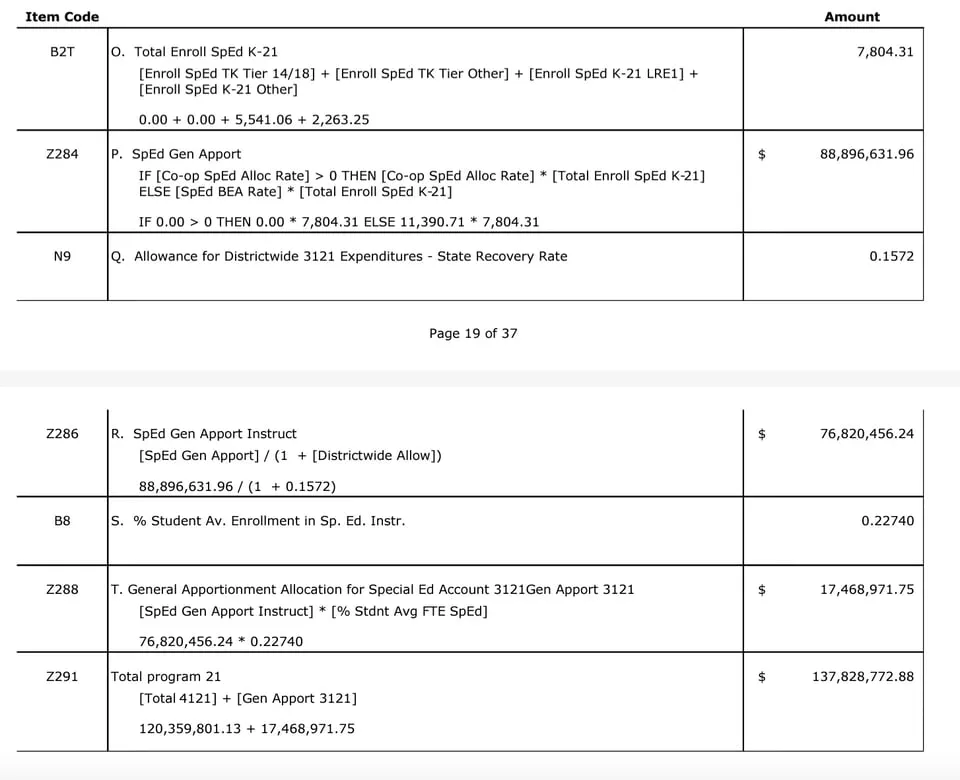

In the 4121 number, it looks like the district put 2,263.25 students in the 1.06 category and 5,541.06 in the 1.12 category, which, when you factor in the basic education allocation for all students (which is 11,390.71), yields Seattle schools about $100.8 million for K-21 disabled state funds.

Take a look below at how they break it all down, it’s sorta fun if you’re into logic, even if it feels like a skeleton’s finger is in your brain. Follow the IF THEN sequences and you’ll get a sense of how I spent my Tuesday morning:

A couple questions. Again, at this point, I’d ask why it breaks down this way, like how’d they assess the students into those categories? I’m also curious about something called a federal funds integration rate of 22.32 works, since it looks like you ultimately have to subtract that in the adjustment process. I have to look that up.

Okay, but that’s not everything. There’s the 3121 general apportionment to think about, which is where the special education multiplier’s b(ii) limitation, the infamous cap, comes into play.

For this grant amount we first take that total number of disabled students and multiply it by that the BEA rate, which again is 11,390.71. All the disabled students together is 7804.31. (I wonder who the .31 of a student is, lol jk.) You get $88.89 million.

It’d be cool if the district got all that money, but it doesn’t. Seems like it’d be an interesting demand to say just give us that amount! It’s like, we’ve got this number of students and the state’s BEA rate is what it is, just give us that money. But yeah, they don’t.

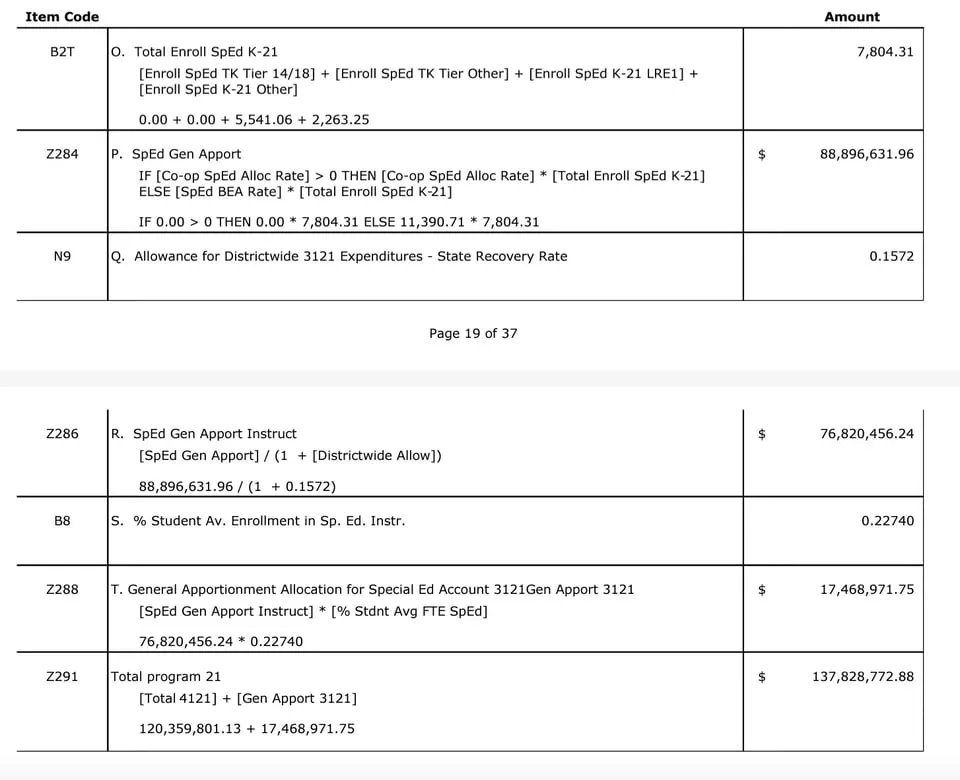

Instead, the state takes that $88 million number and divides it by an “allowance for districtwide expenditures,” what they call a state recovery rate, which is .1572. Here’s the 16(ish?)% rate I mentioned before I think. The law says “if the enrollment percent exceeds 16 percent, the excess cost allocation calculated under (b)(i) of this subsection must be adjusted by multiplying the allocation by 16 percent divided by the enrollment percent.” So when they apply this state recovery rate for the allowance, that brings the general apportionment down again to $76.82 million.

Want to know more about that rate? Too bad. This is the only place place in the whole budget we see this number. How’d they get .1572 rather than 16? If they’re gonna fudge it by .28 why not raise the ceiling rather than lower it? Seems arbitrary to me (it used to be lower at 13.5, and looks like the union fought for and won the increase). As an aside, I found a spreadsheet listing every district in the state and their associated “federal indirect rates” (is that the same as the integration rate?) and the state recovery rates.

Anyway, it’d be cool if the district got that $76.82 million amount, even though it’s less than the first big number. But the district doesn’t get that either. Here’s where we see the b(ii) cap take full effect.

The total number of the disabled students, as a percentage of the student population, is over 16%. It’s 22.74%. So the state takes that $76.82 million number and multiplies it by .2274 and then they get the general apportionment number, which is a relatively paltry $17.46 million. So that’s what the district ends up with.

If I’m following all this right, and I certainly might not be, it looks like the general apportionment number for the state’s special education grant could be as high as $88 million, but because of the b(ii) limitation in the multiplier law, it gets reduced to $17 million. That leaves $71 million on the table that the state just doesn’t want to pay the district, sort of like a private insurance company. Even though the district has these special education needs, the state has a policy—which they insultingly call an allowance—to limit that expenditure, like a private insurance company.

I’m told this policy creates some perverse incentives for the district. Since they’re not going to be reimbursed for all the services they provide disabled students, they’re more hesitant to provide those services, thus creating undercounts. The powerful legal arrangements around provision for disabled students pushes the district to shy away from intensive services that students could really benefit from. (I’ve also heard that there’s a program called the safety net reimbursement system for high cost students, which, for some reason, many students haven’t qualified for, and could net the district more funds.)

I think a movement could reasonably push on this as a demand, like the union has already. I’m hearing rumors this kind of change could be on the docket for the next legislative session and it might help the situation. I don’t know if it’ll keep the schools from closing, but maybe!