Bond/failure

One of my favorite sources of school facilities news is American School and University's Schoolhouse Beat. It's an almost daily and free subscription to articles covering news about both K-12 and higher education facilities. You get a real sense of the system for we have for financing these facilities.

But it's probably more accurately called "systems," since each state and sometimes each region or district has its own set of policies. The coverage reveals some of this complexity.

A story from Provo, Utah caught my eye recently. A group of parents in the Alpine School District are suing that district because it's looking to close five elementary schools. The reason for this closure points to everything that's wrong with the US's capitalist approach to financing school facilities.

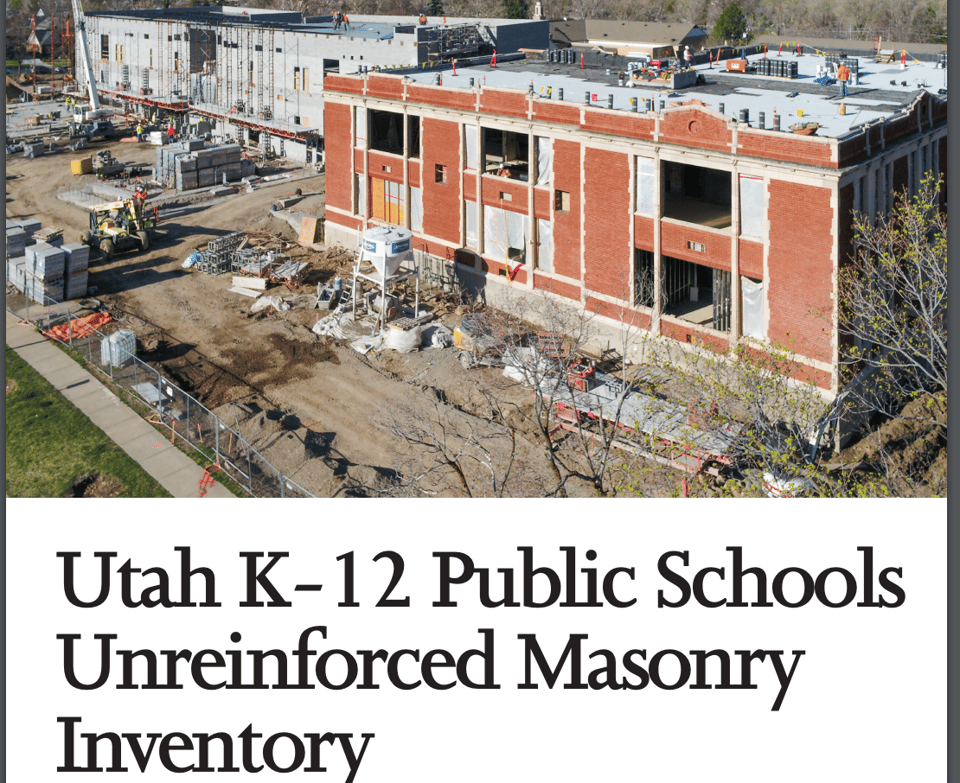

These five schools were listed on a state registry pointing to public buildings that aren't earthquake-safe. The registry is notably called the "Unreinforced Masonry Inventory," which makes me think of all the buildings that collapsed in Turkey recently. If buildings' masonry isn't properly reinforced, it can be quite dangerous. The report notes that much of Utah has a high earthquake hazard.

So the state found that these elementary schools, where little kids and teachers and staff, are spending their days, are not built to withstand an earthquake. The district quite logically took steps to put together a facilities plan to update the buildings so they wouldn't collapse and kill the people in them.

Here we have a paradigm case of what researchers call the "lumpiness" of capital expenditure. The district now had a big, one-time expense they have to find money for: updating the masonry of these elementary schools. Where do they get the money? Like most districts in the US, Alpine district has to get a private loan from Wall Street, on the municipal bond market, to pay for this capital-intensive project. They have to sell their district on the market as an investment commodity to make sure these schools don't kill their kids.

Also like most districts, it has to consult its taxpayers before it can take out that loan. Because the district would have to increase its property taxes by some amount, they need to put it to a vote. If the voters agree to pay a little more in taxes to fund the project then the district can take out the private loan.

Just to pause here for a moment. I generally think voting is great, it's democratic, I completely support it. But when a school district needs to get voter approval from property owners to make sure five of its elementary schools are safe from earthquakes, I don't think this arrangement is the best one we could have. Ideally, private property markets and their value should have nothing to do with this. The district would work with the state and federal government to cover this collective cost with pay-as-you-go grants.

What happened in Alpine School District is a case in point. When you involve private property markets and the people that own that private property, the likelihood that they'll raise taxes on themselves and their property is much lower, since now they have an opportunity to put their own property and paychecks into the equation of whether elementary schools should be safe in case of an earthquake.

Thus, the voters rejected Alpine's bond referendum. They voted no. They didn't want the property values to go up, so they didn't want to pay. This is bad for all kinds of reasons, not least of which is that the district's enrollments have been increasing incrementally over the last decade. They've got more students and now less space for them.

This actually happens pretty frequently. The data is ten years old, but Ballotpedia reports that, for the 40 states that require these referenda, acceptance of bond votes was 72% in 2012. That means that about 30 percent of the time, you wouldn't get the money you needed for your school facilities in these states.

This whole system leads to some perverse outcomes. I just read a very disturbing piece in ProPublica about Idaho school facilities. Districts there need a 2/3 majority to pass bond elections. So the buildings are falling apart. (The bonds that recently passed in three big Texas districts, for instance, wouldn't have passed in Idaho.) Some people, like the unbelievable Paul Dorr, make it their goal in life to thwart bond elections and prevent school districts from getting what they need. He literally said, on record, that "Public education is a sin against God." Wonderful.

This shouldn't be possible. School districts should get public money for their facilities as they need it. They shouldn't have to be entangled in private property relations. The Alpine bond failure, and sheer existence of policies like Idaho's and people like Dorr, is a failure of American capitalism. It's structural.

People in Alpine School District know this intuitively, because a group of parents sued the district for planning to close the five schools they couldn't afford to make safe in earthquakes. Their only other option was to rezone their existing catchment boundaries to make due with the safe school buildings they had. The parents in Alpine were rightly pissed and now they're suing the district.

The terrible irony here is that the school district will have to spend money on legal counsel to resolve the court case. If the case exceeds their allotted budget for legal defense, they may have to raise property taxes.