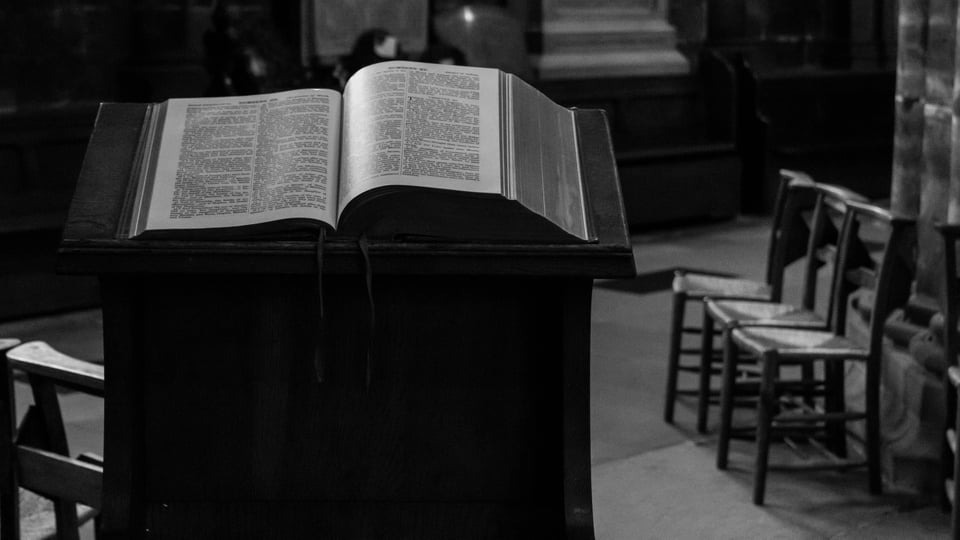

The Poet-Preacher

The challenge and promise of preaching wonder in an utilitarian age.

The latest issue of Comment includes an article by Walter Brueggemann adapted from his book about preaching, Finally Comes the Poet, first published in 1989. In it, Brueggmann advocates for a form of preaching akin to poetry, by which he means "language that moves like Bob Gibson’s fastball, that jumps at the right moment, that breaks open old worlds with surprise, abrasion, and pace."

Such poetic preaching is urgently needed and not only because "the gospel is simply an old habit among us." More than familiarity, our experience of the gospel has been diminished by the society which shapes our imaginations. "[Our] technical way of thinking reduces mystery to problem, transforms assurance into certitude, revises quality into quantity, and so takes the categories of biblical faith and represents them in manageable shapes."

Brueggmann goes on to show how poetic preaching can break through these reductionist forms and allow the gospel to sing its subversive song. For now, though, I'm interested in the claim that the particular nature of our cultural formation - mechanistic, reductionist - requires a radically different form of communication. I'm interested because I'm not sure Brueggmann's assumption about the reducing nature of our society is, even all these years later, self-evident to many of us who climb into pulpits each Sunday.

In Brueggmann's warnings I hear hints of what Pope Francis, a few decades later, would describe as the "technocratic paradigm" in Laudato Si'. The following selection gives an idea about what he means.

This paradigm exalts the concept of a subject who, using logical and rational procedures, progressively approaches and gains control over an external object. This subject makes every effort to establish the scientific and experimental method, which in itself is already a technique of possession, mastery and transformation. It is as if the subject were to find itself in the presence of something formless, completely open to manipulation. Men and women have constantly intervened in nature, but for a long time this meant being in tune with and respecting the possibilities offered by the things themselves. It was a matter of receiving what nature itself allowed, as if from its own hand. Now, by contrast, we are the ones to lay our hands on things, attempting to extract everything possible from them while frequently ignoring or forgetting the reality in front of us. Human beings and material objects no longer extend a friendly hand to one another; the relationship has become confrontational. This has made it easy to accept the idea of infinite or unlimited growth, which proves so attractive to economists, financiers and experts in technology.

For Francis, contemporary people, unlike our not-so-distant ancestors, inhabit a world which has been made completely subject to domination and extraction. Not only has the earth and its creatures been reduced to exploitable resources, people too have been shaped by the technocratic paradigm. In so many different ways, we've been told that we are cogs in some corporation's wealth-generating wheels. Or, rather than being producers or even consumers, we are now the products whose intimate details are monetized and sold.

It is a reduced and commodified people who show up for Sunday worship. So pervasive and powerful is our utilitarian age that many of us don't know to want a different kind of word from the preacher. We assume that, like the other narratives with which we're familiar, the gospel story is meant to help us survive the status quo.

I've a sneaking suspicion that many of us pastors have succumbed to these diminished expectations as well. Why else do we so quickly grasp for the technological tools offered by the profiteers? Why else do we embrace the ways of marketers and advertisers, the assumptions of the capitalists and hoarders? We justify their use by dreaming of those we will reach, those who would otherwise exceed our limited grasp. Conceding the logic of scarcity, we compete for attention and commitment. We invest vast sums in eye-catching websites, livestreaming cameras, climate-controlled sanctuaries, and impressive audio visual systems. Or, we're jealous of those who can.

"We shall not be the community we hope to be," warns Brueggmann, "if our primary communications are in modes of utilitarian technology and managed, conformed values." We shall not, we might add, become the sorts of people who follow a despised and rejected Messiah if these are the modes we rely on.

Not that a contemporary congregation can completely avoid the diminished values of our technocratic age. We ought to be gracious and honest about our capacity. But if we are to begin moving to the rhythms of a different song, we could do worse than starting with poetic preaching. Such preachers will be honest with themselves about our own captivity to scarcity and utilitarianism. We'll confess the times we treat the People of God as a means to our predetermined end. We'll step into the pulpit with fear and trembling, not simply for the Word we proclaim but because of the poetic folly which characterizes our proclamation.

The poet-preacher also steps nervously into the sermon because she knows the people haven't been conditioned for poetry. We are looking for the practical stuff of self-help and how-to. A sermon meant to inculcate wonder and worship, repentance and rebirth, hope and more hope... well, this is a strange and seemingly useless thing to those who traffic in utility and productivity. Preacher, what's the point?

The gospel, though, is a world unto itself, a world being woven by Word and Spirit into the exploited and exhausted landscapes of our lives. And such a world simply cannot be described or displayed with the tools of our technocratic age. And despite the reducing conditioning we've all experienced, the congregation senses this too. We may not come ready for the poetic gospel word but buried beneath our diminished desires is a hunger for the real thing.

Deep calls to deep- the expansive Word proclaimed reverberates in a people's imaginations, waking us up to forgotten ways of living and loving. Alerting our numbed hearts to the resurrecting presence of good news.

(Photo credit: David Gallie.)

The View From Here

Book Updates

My editor sent me the Plundered copyedited manuscript earlier this week. I've got about a month to go over it before sending it back. The other thing I'm working on is reaching out to potential endorsers. If you've got any suggestions, please let me know!