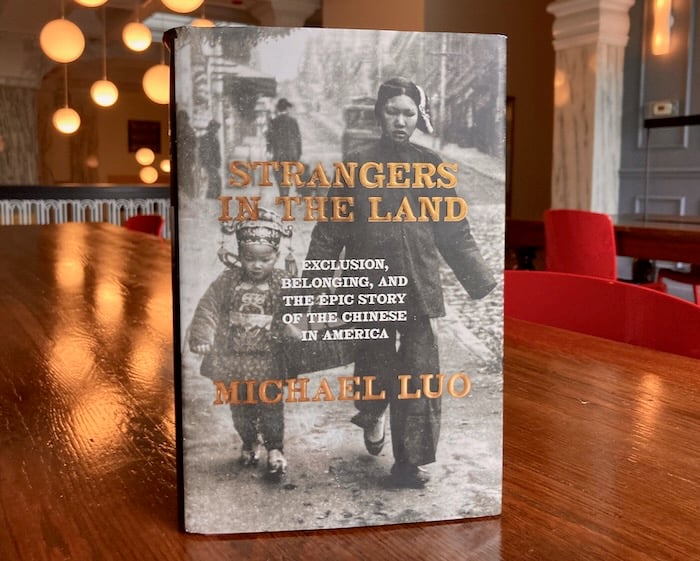

Strangers in the Land

Echoes from the early days of Chinese migration

I recently finished Michael Luo’s phenomenal new book, Strangers in the Land: Exclusion, Belonging, and the Epic Story of the Chinese in America. I’ve read some really good books this year, but Lou’s riveting history of the first Chinese migrants to the United States is at the top of the list. Drawn extensively from primary sources, Luo writes with the precision and grace you’d expect from a The New Yorker editor that he is. Covering the global push and pull factors which attracted and repelled Chinese migrants to and from America’s western shore, the author excavates story after intimate story which explores these forces through the men, women, and children most impacted by them.

Strangers in the Land deserves a thorough review (here’s a good one in the The New York Times) but that’s not what I want to do here. Throughout the book, as he told the story of the first group of people to be systematically and legally excluded from the country, I found it hard not to consider the contemporary analogues. As we live under a political regime which scapegoats migrants while pursuing a policy of mass deportation, it was both troubling and instructive to hear themes from a previous period echoing in our own days. Here are a few of those thematic echoes.

Exclusion and Expulsion: Many readers will be familiar with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which prohibited Chinese immigration while also denying the possibility of citizenship to American residents of Chinese descent. Using political power to exclude specific groups of people is a tactic the country continues to use, as evidenced by the presidential administration’s directive to deny asylum claims without a hearing and barring citizens from twelve nations from traveling to the U.S.

In the era covered by Strangers, exclusion wasn’t enough; Chinese migrants were often expelled from cities, towns, and the country itself. Expulsion was often deadly, with some migrants being murdered and others losing property to mob violence. Liu writes that, at the turn of the century, immigration officers “began conducting regular raids on Chinese businesses, schools, and other establishments.” In one case in Boston, officers “approached the quarter in pairs to avoid raising alarm” before “encircling the the quarter and sealing off escape routes.” Reading this, it was hard not to leap forward to the ICE raids that are terrorizing immigrant communities and neighborhoods today.

In another contemporary echo, Liu writes about what we’d now call “family separation” as practiced by immigration inspectors on Angel Island where the majority of Chinese migrants were processed after their arrival in the U.S. in the early 1900s. Remembering the experience of her grandmother who was separated from her children for fifteen months, Connie Young Yu “later described the emotional toll inflicted upon [her] family as ‘incalculable.’”

Money: While it’s not the focus of Liu’s history, the role of money and its many relations – poverty, wealth, greed, etc – runs throughout the book. The Chinese migrants were provoked to leave everything and everyone behind for the chance to escape the grinding poverty then impacting much of China. It was the discovery of gold in California that accelerated migration and made the Chinese men welcomed when the need for more men was high and a perceived threat as competition grew. When labor was in high demand, as with the construction of the transcontinental railroad, Chinese migrants were described as industrious and loyal; when wages were driven down and capital consolidated, they were maligned as perpetual foreigners who could never assimilate to American culture.

One can almost always find, just beneath the racist stereotypes leveled at the Chinese migrants to justify their exclusion and expulsion, severe economic anxieties. Similarly, in today’s racist rhetoric which associates immigration with criminality, we can often find material fears about stagnant wages, housing prices, the cost of higher education, and so on. By defining certain of the country’s residents as not “real” Americans because of racialized stereotypes, populist mobs and elite power-brokers could (and still do) abuse the non-citizen, vulnerable migrants for their own economic ends.

Solidarity: While Lou highlights the occasional white pastor and politician who advocated for their recently arrived neighbors, it was the intersection of Black American’s concerns with those of the Chinese migrants which stands out. For example, in a speech delivered in Boston in 1869, Frederick Douglass responded to growing anti-Chinese sentiment by advocating for their right to settle in America. “Would you have them naturalized,” he asked, “and have them invested with all the rights of American citizenship? I would. Would you allow them to vote? I would. Would you allow them to hold office? I would.”

May God grant us such boundary-crossing solidarity today.

The View From Here

I woke Maggie up earlier than she’d typically rise during her summer break one morning this week so that we could walk to a nearby bakery and then over to the lake. It’s been excessively humid in Chicago and a quick wade in the lake was a great way to start the day.