Reconciliation and Warfare

"It is an outrage upon the soul, a war upon the immortal spirit..."

In the years after he freed himself from slavery, Frederick Douglass traveled to England with his abolitionist message. While there, with the security of the Atlantic Ocean between them, Douglass wrote a letter to the man who’d enslaved him, Thomas Auld, on the occasion of the ten-year anniversary of his self-emancipation. The renowned orator used the impressive power of his pen to make clear to the man who’d claimed to be his master the extent of his depravity. “Your wickedness and cruelty,” wrote Douglass, “committed in this respect on your fellow-creatures, are greater than all the stripes you have laid upon my back or theirs. It is an outrage upon the soul, a war upon the immortal spirit, and one for which you must give an account at the bar of our common Father and Creator.” (Emphasis mine.)

In addition to the innumerable harms committed against those they enslaved, the abolitionist understood Auld, other enslavers, and the beneficiaries of the slave economy to be warring against the God who created Douglass and his family in the divine image.

The acknowledgement of evil, of the spiritual warfare intrinsic to confronting systems of cruelty, inequity, and exploitation, is critical to a Christian understanding of racial reconciliation and justice. It’s not inanimate societal structures or uniquely wicked individuals who are the source of the opposition we face. As we represent God’s righteousness in unjust situations and systems, we find ourselves battling “against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this age, against spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places.” (Ephesians 6:12)

This theological understanding animates Malcolm Foley’s new book, The Anti-Greed Gospel, in which he claims that the invention of race was not “primarily about hate and ignorance. It’s about greed.” It’s an argument I’m deeply sympathetic to and it allows Foley to connect race with the idolatrous power of Mammon. “The stakes are cosmic,” he writes, “we are engaged in a battle of gods.”

Often, though, when it comes to ministries of racial justice and reconciliation, the fact of spiritual warfare gets lost in the search for effective strategies and enlightening information. We attend conferences which promise to inspire our commitment to racial righteousness and join learning cohorts with like-minded ministry leaders. I’m grateful for these resources and have benefited from many of them, but I’ve also noticed how easy it is to begin relying on these tools rather than on the “whole armor of God” which follows Paul’s warning about the true nature of our fight.

Thankfully, there are contemporary examples of leaders who are not confused about the necessary weapons of our warfare. Late last month the AME Church Council of Bishops shared an Episcopal Statement in response to the immediate actions of the new presidential administration. The bishops identified six things AME congregations can do in this environment. First,

we must recognize that we are at war and fighting as the Book of Ephesians warns "against spiritual wickedness in high places." Elected, ordained, appointed, nationalist, terroristic forces. This fight is not simply political; this is spiritual warfare. Therefore, we must put on "the whole armor of God" and fight the good fight of faith.

So, how do we know if we our efforts at racial justice and reconciliation are engaging the true fight? To begin with, we can notice what role prayer plays in our efforts. A community which recognizes spiritual warfare won’t get distracted by the silly debates about whether it’s more important to respond to injustice with action or prayer. We understand that our actions will be discerned in prayer and that prayer is never devoid of action. And because the cause of racial exploitation and exclusion is deeper than its many manifestations, we’ll make prayer – and, at times, fasting – a regular rhythm of our justice efforts.

And second, we’ll notice whether, in our attempts to nurture reconciliation, we ever dehumanize those who aggravate divisions and profit from exploitation. This week Elon Musk referred to groups of people as “the parasite class.” It was unabashed dehumanization of the sort that has become increasingly common among those representing the presidential administration. It’s tempting, for me, when confronted with such objectively degrading slander to respond in kind. I want to see those who engage in such blasphemy as less than the humans they are; it gives me license to respond to cruelty with more cruelty.

Of course, the instant we succumb to dehumanization, the battle has been lost. We’ve aligned our minds and methods with the enemy’s tactics of deception and destruction. Recognizing this means we’ll interpret the humanizing nature of our speech and tactics not as some vague spirituality but as visible, material choices to remain on the side of God’s righteousness and justice.

(Photo credit: Aadi Samuel)

This is the fourth part of an ongoing thinking-out-loud series about the faith-rooted racial reconciliation movement during these chaotic days. Here are part one, part two and part three.

Brown Faces, White Spaces

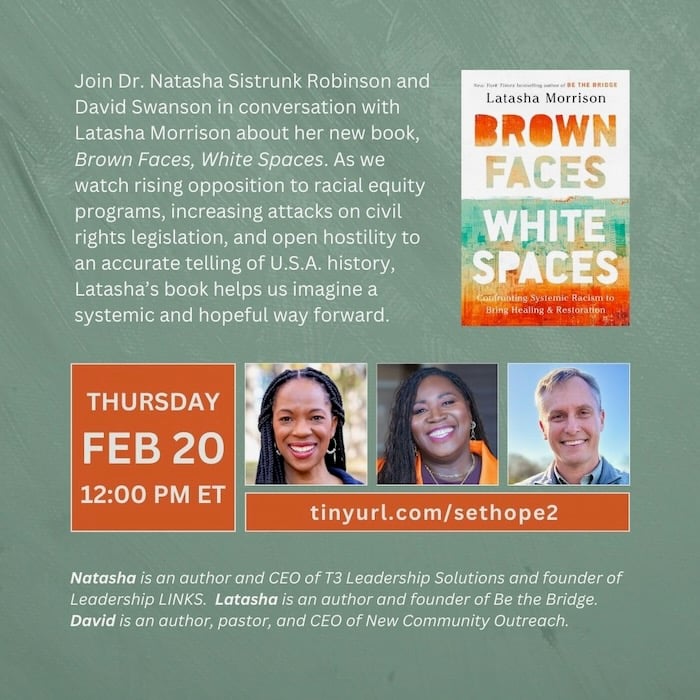

Following up on our recent conversation, next week Dr. Natasha Sistrunk Robinson and I will engage our friend Latasha Morrison in conversation about her new book, Brown Faces, White Spaces. You can register here to join us.

The View From Here

A snowy train ride to the loop on a chilly morning earlier in the week.