Reconciliation and Repair

Multiracial churches that aren't (only) for white people

When white people join an intentionally multiracial congregation, they are often hoping to form racially diverse friendships. Compared with other racial groups, white people continue to live in the most segregated communities. This means that, by the time they’re seeking a multiracial church to join, a white person has typically experienced some sort of awakening in which they’ve come to recognize the segregation they’d previously overlooked. They come to this new, diverse church looking for something different.

Additionally, white culture is generally oriented toward the individual rather than the collective. This means that most white people who wake up to racial segregation are primed to think about their experience through a relational lens. This person will join a congregation committed to racial reconciliation expecting to experience the kind of friendship that segregation made impossible and to evaluate the success of their new church through this highly relational perspective.

Many multiracial churches have been built on the assumptions and needs of recently awakened white people. Such churches help white people move out of their segregated relational networks but do very little to address the material realities which burden the lives of many of the white person’s new friends. Which is to say that a multiracial church whose mission is limited to reconciling relationships is a multiracial church for white people. As I wrote in my first book,

[Racial] segregation is less about separateness than about the material damage of our racially unjust society. It is possible to build a multiracial ministry that leaves structures of racism and white supremacy totally undisturbed. In fact, it is easy for multiracial churches to bend toward the comfort of white people rather than the well-being of people of color.

While there are those in the racial justice world who, because of white-centered relational assumptions, simply set aside the possibility of reconciling friendship networks. For a number of reasons, mostly because I’m a Christian, I can’t follow their lead. But if reconciling relationships are going to be good for everyone in the congregation, another r-word needs to balance it out: repair.

A Christian reconciliation paradigm which includes repair is sensitive to humanity’s vocation, the witness of Scripture, and the times in which we live. In Plundered I argue that humanity’s God-given calling is to live as the world’s priestly caretakers. Moving freely between the Creator and our fellow creatures, humanity is meant to call creation to worship its Creator and to bless our creaturely kin with the Creator’s love. We enact our priestly work as caretakers, giving and receiving affectionate care within our local communities of creation. Honoring our vocation as caretaking priests is meant leave the places and people we love better off simply because of our presence.

Scripture reveals that repair can be applied to relationships, but it isn’t limited to relationships. Isaiah writes to a besieged people of a hopeful day to come when, “Your ancient ruins shall be rebuilt; you shall raise up the foundations of many generations; you shall be called the repairer of the breach, the restorer of streets to live in.” (58:12) Here is a thoroughly material and social vision of repair. Of course it includes the reconciliation of individuals to one another, but it does not neglect the societal structures impacting those same individuals.

Finally, including repair in our reconciliation paradigms opens our eyes to the devastation we’ve learned to accommodate. A reconciling community is called to much more than friendship-making amidst mass deportation, climate change, and the lucrative business of war-mongering. No, representatives of God’s kingdom spill themselves like so much yeast and seed into the cracked places and among the shattered people, attentive to the Spirit’s renewal. Where others can only see valleys filled with dry bones, God’s reconciling communities will discern watersheds to protect, redlined neighborhoods to resource, and tyrants disguised as politicians and technocrats to defy. Not because we are capable of saving anything or anyone, but because we’ve come to love and be loved by our places and their people.

(Photo credit: Feyza Daştan)

This is the third part of an ongoing series about the faith-rooted racial reconciliation movement during these chaotic days. Here’s part one and part two.

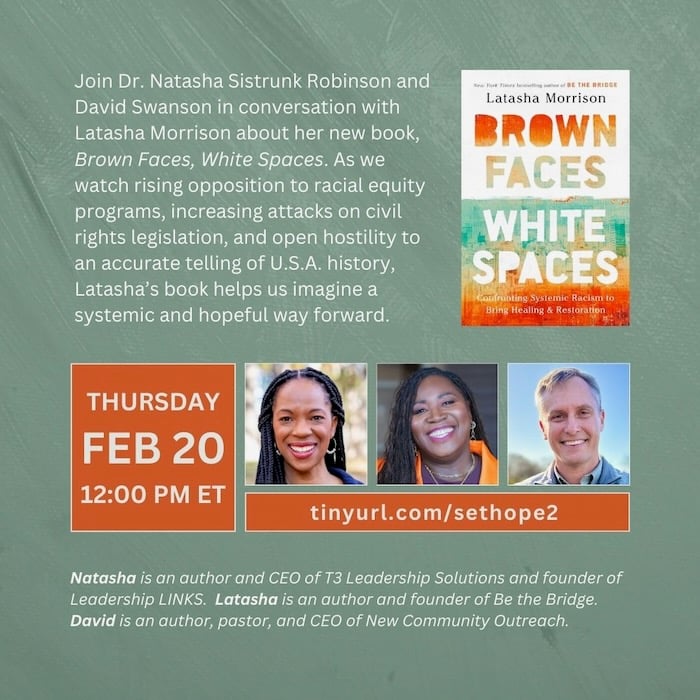

Brown Faces, White Spaces

Following up on our recent conversation, later this month Dr. Natasha Sistrunk Robinson and I will engage our friend Latasha Morrison in conversation about her new book, Brown Faces, White Spaces. You can register here to join us.