Reconciliation and Politics

Racial reconciliation as "being political"

We’re living through a time of exacerbated partisan polarization. One implication of this for racially reconciling churches is that much of our ministry will be misunderstood through partisan frameworks. This can be summarized with the feedback some pastors receive when beginning to apply the obligations of discipleship to racial injustice: “Why are you being political? Just stick to the gospel!”

As crazy-making as this kind of feedback can be, it’s not surprising when coming from those whose spiritual formation has ignored certain cultural realities. It’s often the case that the same person who views racial justice as problematically “political” wouldn’t consider, for example, abortion through the same framework. If a Christian has been discipled in communities which have outsourced many social justice concerns to partisan media sources, it’s not surprising when they struggle to make the connection between the mandates of Scripture and responding to systemic racism and white supremacy. This person has been led to understand abortion as a theological concern and racism as a so-called political one.

Though they’ve likely conflated partisanship with politics, the people accusing their pastor of being political are at least partially correct. Most simply, politics is how a polis – a citizenry – organizes itself and pursues its priorities. Though we were once “strangers and aliens,” according to Paul, disciples of Jesus are now “fellow citizens with the saints and also members of the household of God.” (Ephesians 2:19) Unlike those whose politics are oriented by the whims of a nation’s elected officials, cultural trendsetters, or fundamentalist ideologues, the Christian’s “citizenship is in heaven.” (Philippians 3:20) Which is to say that our politics, our churches’ norms and priorities, are organized around God’s good and righteous will.

The politics of any local church, existing as an alternative polis, will often appear out-of-step with the dominant politics in its community. Fundamentally, claiming that Jesus is Lord means renouncing all the ways a society’s politics demand our allegiance. However, many Christians in this country come from traditions which have long been enmeshed in our culture’s political norms and priorities. As members of the cultural majority, white Christians, both conservative and liberal, have been particularly prone to syncretizing Christian faith with partisan politics. As long as these congregations conform their message and ministries to the assumptions of the political majority, it won’t feel to their members as though the churches are being political.

It’s much harder for intentionally multiracial churches to get away with this kind of political conformity disguised as political neutrality. It’s true that even in these anti-DEI days, most places in this country would affirm the value of racial diversity. But a congregation which commits to undermining the material forces which maintain the racial hierarchy should expect a less enthusiastic reception.

Take, for example, the ongoing connection between race and economic exploitation. In Plundered I write,

It’s commonly understood that racism led to the genocide of Native Americans and the theft of their lands as well as the kidnapping and enslavement of Africans. But this is a chronological mistake… By identifying entire races who were supposedly intellectually and morally inferior, those identified as white could treat other humans similarly to how they treated new lands, as sites of extraction… For many white Christians, the racial hierarchy provided theological justification for insatiable greed.

A racially reconciling church which understands this historic rationale behind the invention of race won’t be content to attract a diverse roomful of people. Rather, the community, the polis, will understand the importance of resisting the crooked economic system for which race has provided the explanatory narrative. Given how contrary to the dominant culture this kind of church is, its politics will inevitably be very visible, a marked contrast to the cultural genuflections at the altar of extractive capitalism.

(Here is another reason that multiracial churches need the Black church tradition. Given their location outside of mainstream American politics, these churches have generally seen those politics for what they are. When Ida B. Wells wrote that the “appeal to the white man’s pocket has ever been more effectual than all the appeals ever made to his conscience,” she was noting the material, extractive intentions behind the lynchings she was then battling. It’s no surprise that it is Black churches organizing the boycotts targeting the corporations backing down from their racial justice commitments.)

The point is not that racially reconciling churches are more political than other churches, but that these congregations don’t have the luxury of pretending to not be political. To exist as a purposefully racially righteous community in a racialized society, built on plundered communities and justified, in Bryan Stevenson’s words, by the “narrative of racial difference,” is to be a visibly counter-polis organized by a politics radically at odds with the status quo.

To be a racially reconciling church, then, is to embrace being political– to grasp the absolutely distinct type of community the citizens of heaven are called to embody along with the surprising politics such a community requires.

(Photo credit: Caleb Oquendo.)

This is the sixth part of an ongoing thinking-out-loud series about the faith-rooted racial reconciliation movement during these chaotic days. Here are part one, part two, part three, part four, and part five.

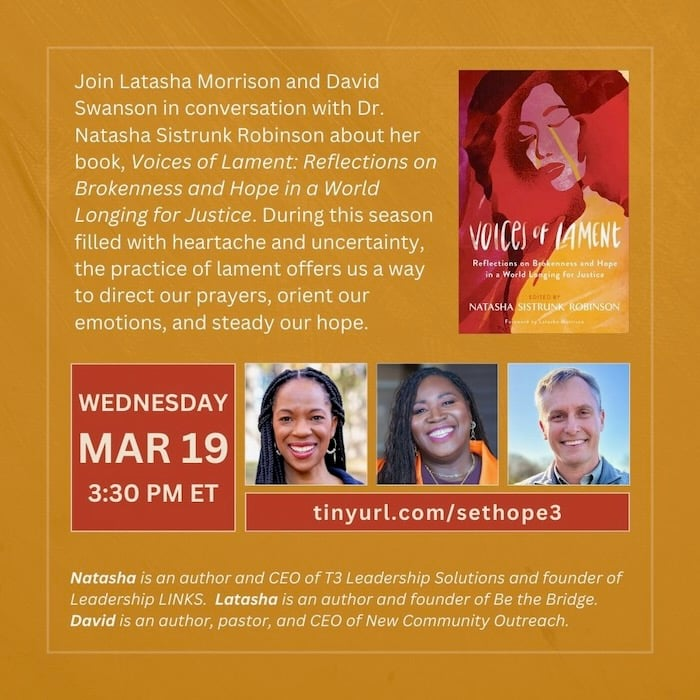

We’re a week away from another conversation with these two friends, this one centered the beautiful book edited by Dr. Natasha Sistrunk Robinson, Voices of Lament. I hope you can join us.