Reconciliation and Place

The patient work of making a home

One of the motivations behind Plundered was my experience of the precarious nature of racial reconciliation. Of course, congregational life is rarely predictable because the lives of its members are rarely predictable. Still, there’s something uniquely tenuous about participating in a racially reconciling church.

This characteristic of multiracial, multicultural community comes, in part, from how rarely most of us have experienced community that is genuinely culturally diverse. It’s true that white people remain the most relationally segregated group of people in the USA. It’s also true that most people, regardless of race, have found their safest community among racially and culturally similar people. It’s not uncommon for someone in our church to tell me that a particular person in the congregation is their first true friend of a certain race or ethnicity. The very newness of the racially reconciling experience introduces an element of unpredictability.

There’s another source of uncertainty that impacts multiracial churches. The volatility and cruelty common in a racialized society is particularly felt by a community prioritizing reconciliation. Over our church’s fifteen years, there have been countless of these instances which have impacted members of the church: the murder and subsequent cover-up of Laquan McDonald in Chicago; the massacre at Mother Emmanuel AME in Charleston by an avowed white supremacist; the murder of the six women of Asian descent in Atlanta; the election and reelection of a man who continues to demonize immigrants and refugees. These external events impact individuals and groups in the congregation and, often, cause them to wonder how others in the church think about these traumatizing events. In my experience, it’s often these moments which cause people to wonder whether a multiracial church can ever truly be home for them.

Given these destabilizing forces, I’ve often imagined reconciliation ministry as an ongoing attempt to stabilize a small boat on tumultuous seas, or trying to stay upright while walking across shifting and shaking ground, or trying to balance a very wobbly and very fragile plate on a fingertip, or… you get the idea.

At some point, though, my image shifted. What caring for a multiracial church most felt like to me was trying to remain relationally connected to a community made up of people who are each hovering a few inches above the ground. Just as it seems like we are coming together, a gust of wind threatens to set us adrift.

This image of detached community helped me recognize that my vision for reconciliation had ignored a critical member of the community: our place. Typically, conversations and strategies about racial justice and reconciliation ignore the place where these reconciling communities have made their home. If it is thought about at all, place is simply the backdrop for the real work of multiracial solidarity and justice.

The more I considered the absence of place in our reconciliation efforts, the more absurd it seemed. In Scripture, the redemptive work of God is always connected to place. Living as God’s people involved caring for their places, including the people and animals which made them their homes. The ministry of Jesus can only be understood within the specifics of his Galilean place. On and on we could go; the redemptive work of God is always expressed in relationship to particular places and their people.

I wonder if we’ve pursued reconciliation while ignoring our relationship to place because we’ve lived detached from place long enough that we’ve forgotten how strange and damaging this way of life is. This inhumane detachment isn’t accidental. “When human life and the earth itself are reduced to commodity forms,” writes Daniel Castillo, “they both become acutely vulnerable to various forms of abuse and exploitation.” Pope Francis describes this detaching, commodifying impulse as the “technocratic paradigm.” Castillo describes it as a “500-year project” of colonialism. Macarena Gómez-Barris sees “extractive capitalism” behind the trajectory of our severed relationship with place. However it is described, the point is that there is a long history in which powerful forces have made what was meant to be an affection relationship between a place and its people increasingly fraught.

This disconnection from place, while common to contemporary life, is experienced differently. Those with the privilege of mobility are prone to view place in terms of what they can take from it, whether a higher-paying job, a more status-granting university, or a climate more suitable to one’s leisure preferences. Those who come from, as Castillo describes them, the world’s “zones of extraction” experience this disconnection more violently: climate refugees, asylum seekers, migrants fleeing racial terror, residents subject to polluted air, etc. The degrees of severing are very different even if the results – a tenuous relationship to place – are similar.

I’m convinced that recognizing our disconnection from place is critical for reconciling churches for two reasons. First, these ministries are primed to respond to the forces tearing our world apart. Understanding the reconciling logic of the gospel, intentionally multiracial congregations have the character and disposition to engage in the slow, patient work of making a home together in our places.

Second, by including our places – Creation itself – in our reconciliation paradigms, we leave behind our tenuous, floating-above-the-ground tendencies. By learning to reattach to our places, we discover verdant soil into which we can sink our stabilizing roots. External gusts of wind will still come and there will always be the internal challenges which come with individuals learning to be a people, but now the congregation has shared ground from which to contribute to and care for their community.

How we reconcile with our places is the creative work that local, rooted congregations have the joy of discerning. The ministry of reconciliation – whether with one another or the places which are slowly becoming home – can never be franchised. It is for particular people, growing to love their particular places to discover together.

(Photo credit: Kelly.)

This is the eighth part of an ongoing thinking-out-loud series about the faith-rooted racial reconciliation movement during these chaotic days. You can find previous entries here: part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six, and part seven.

Plundered Webinar

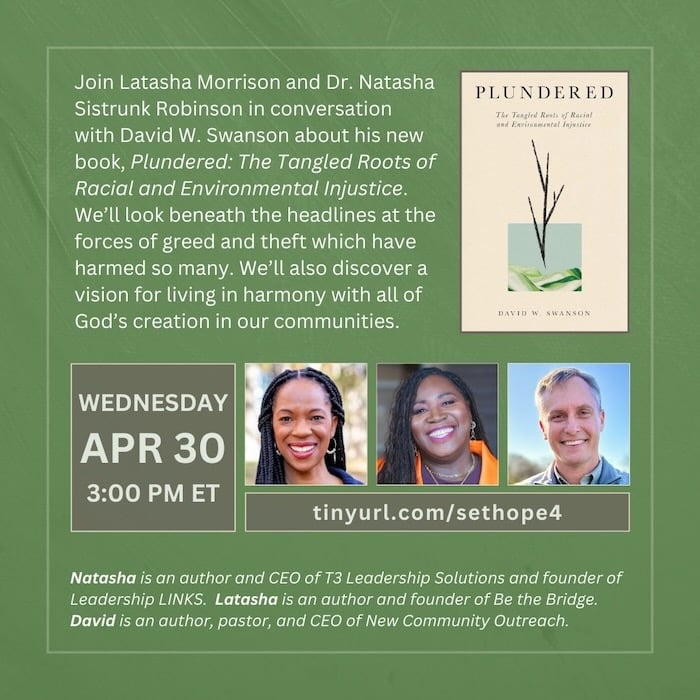

I’ve been so grateful for the monthly conversations Latasha Morrison, Dr. Natasha Sistrunk, and I’ve been hosting this year. Our next one, on April 30, will use my book as a jumping off point. I hope you can join us.

Whitworth Ministry Summit

I’ve mentioned this in a previous newsletter, but I had a video call with the summit organizer, speakers, and worship leader earlier this week and am genuinely excited about what is bubbling up. If there’s any way you can get to Spokane in late June, I don’t think you’ll be disappointed!