Reconciliation and Joy

Potlucks, gardens, and joy in the Holy Ghost

“One last question,” asked the professor who’d invited me to join his class for a lecture about racial reconciliation. “You’ve described a lot of the challenges and difficulties related to reconciliation. But is it good?” It was a reasonable question. I’d spent a lot of time describing the social dynamics and history which make multiracial congregations rare. I’d also talked about some of the ways racial whiteness exerts its force to undermine multicultural community leading multiracial churches to operate as a monoculture. Is racial reconciliation good?

There’s an easy way to answer this, which is to make the case for the good things racial reconciliation does. It is good for racism to be confronted, for social barriers to be crossed, for injustice to be identified, and for isolating segregation to be transgressed. Theologically speaking, it’s very good for a church to bear witness to the kind of righteous belonging that the gospel brings to life. But that’s not what the professor was asking; he wanted to know if the experience of reconciliation, the day-to-day ministry of reconciliation is good.

Over the years, I’ve noticed that multiracial, justice-oriented congregations attract earnest people. I should know, I’m one of them! These are people with a keen sense of what is wrong in the world, how things could be better, and why Jesus calls us to be about that better-making work. And while these are definitely the people you’d want by your side when going up against long odds, we’re not always the first ones you’d invite to a party. We’ll end up rehearing a litany of the president’s latest terrible choices or inviting you to the next Tesla Takedown protest when you were just hoping for a fun evening. Though we’re motivate by a vision of goodness, it doesn’t always seem like we’re enjoying ourselves in the process.

In fact, racial reconciliation isn’t just good as a goal, it’s joyful as an experience. Not always, of course; there is plenty of struggle, opposition, and defeat along the way. But the women and men who continue to nurture reconciling community over the long-haul are sustained by more than a vision of the good; it’s the joy of multiracial solidarity that keeps us going.

As I think about my own life, there’s a lot of evidence of the joy of reconciliation. Can I give you a couple of glimpses? Years ago, this introverted pastor recognized that any church that depended on me to foster community was always going to be supremely stunted. So the church began hosting potlucks on the first Sunday of each month. For nearly 15 years, following the celebration of the Lord’s Supper, we roll out a bunch of round tables, set up the food, and settle in to eat, talk, and laugh. There’s lot’s of laughing. I’ll sometimes look around the gym, full of kids and adults sharing food and stories, and truly wonder at the community God has gathered to himself. It’s impossible not to rejoice.

Another glimpse: Our church’s nonprofit organizes a community garden on the grounds of a local elementary school. Around 8:30 each summer Saturday morning, volunteers begin gathering to water, weed, and harvest whatever herbs and vegetables are ripe. These are added to a delivery of surplus produce from a friend’s suburban farm and placed into bags that are shared with our neighbors. There’s no happier place to be in Chicago on a Saturday morning. Neighbors from the senior living facility across from the school hang out with young adults, a bit sweaty and grimy from gardening. Little kids help sort and bag the produce while neighbors catch up on the wooden bench near the distribution table. In a city that remains predictably segregated by race, this little garden nurtures a riot of diversity.

But while these snapshots provide some evidence for the joyful experience of reconciliation, they don’t quite get at why joy can be found here. For this, we need Jesus. The author of Hebrews writes that it was “for the joy that was set before him” that Jesus endured the cross. That joy includes the reconciliation of all things which Jesus accomplished through his death and resurrection. When we align our priorities and decisions with Christ’s reconciliation, we are doing more than just agreeing with God's good purposes; we are wading into the river of God’s joy. Delicious potlucks and bountiful garden harvests are small expressions of the kingdom of God which, as the King James puts it, is “righteousness, and peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost.”

(Photo credit: Miguel Á. Padriñán.)

This is the seventh part of an ongoing thinking-out-loud series about the faith-rooted racial reconciliation movement during these chaotic days. You can find previous entries here: part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, and part six.

Voices of Lament

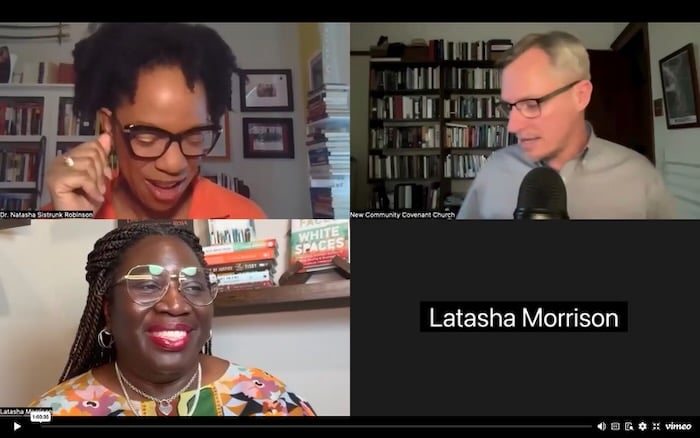

Thanks to everyone who joined Latasha Morrison, Dr. Natasha Sistrunk Robinson, and me earlier this week. If you missed our conversation about lament, you can watch it here any time.

The View From Here

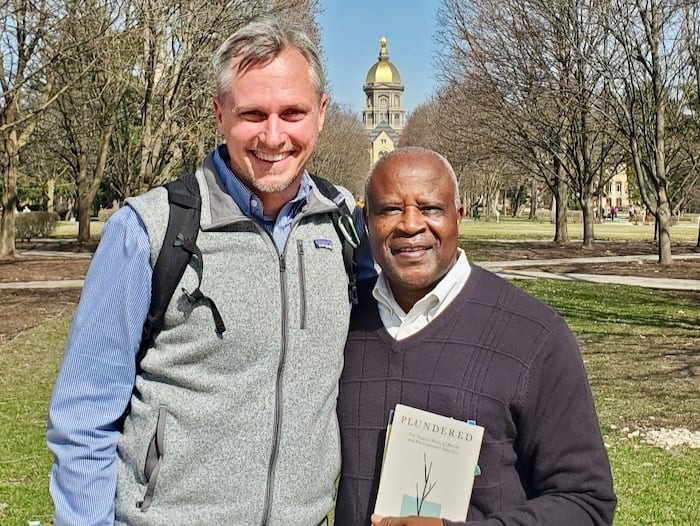

I had the immense privilege of spending Thursday morning with Father Emmanuel Katongole at Notre Dame. The author of a whole bunch of books – Born of Lament is on the top of my stack – and someone I’ve looked up to from a distance for a long time, the chance to talk about reconciliation, environmentalism, and his work in Uganda was such a gift.