Questioning the Brown v. Board Model of Reconciliation

When proximity to whiteness isn't the goal.

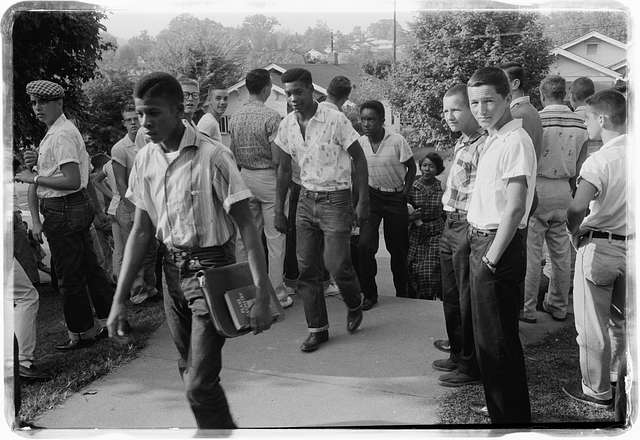

The 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision struck down legislation allowing “separate but equal” racial segregation in public schools. A year later, the court ordered that states desegregate their public schools “with all deliberate speed.” That same year, Zora Neale Hurston, the author and anthropologist, wrote a short essay in which she questioned the conventional wisdom that Brown would benefit African American students. Assuming that at least some “Negro schools” had access to “prepared instructors and instructions, then there is nothing different [about these schools] except the presence of white people.”

Hurston’s concern, as she elaborated a couple of years later, had to do with the assumption that Black people would be inherently better off by integrating with white people. “It has to be believed,” she wrote, “that mere physical contact is advancement itself… One has to be persuaded that a Negro suffers enormously by being deprived of physical contact with the Whites and be willing to pay a terrible price to gain it.” The price Hurston was thinking about was paid, for example, by an African American girl who integrated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas and was ambushed by a group of white girls who forced “her head into the toilet bowl.”

Derrick Bell, one of the NAACP lawyers who worked on school desegregation legislation, eventually came to see the court’s decision from Hurston’s perspective. Looking back on those years, he writes in Silent Covenants, “We were aware that using court orders to send black students into white schools where they were not wanted could be dangerous and always traumatic. For a long time, I pointed to the strong kids who survived and even prospered under the pressures… Regrettably, I paid far less attention to all those students less able to overcome the hostility and the sense of alienation they faced in mainly white schools. They faired poorly or dropped out of school. Truly, these were the real victims of the great school desegregation campaign.”

The negative impact of legislated desegregation, according to Hurston and Bell, transcended the experience of individual students. “When districts finally admitted more than a token number of black students to previously white schools,” writes Bell, “the action usually resulted in closing black schools, dismissing black teachers, and demoting (and often degrading) black principals.” Legislation may have led to some levels of public school integration, but the ongoing presence of white supremacy ensured that anti-Black racism continued it's ugly impact, both personally and structurally.

I’m reflecting on Hurston and Bell’s critical observations not as a legal expert or a school administrator but as a pastor of an intentionally multiethnic church. For some time, much of the multiethnic church movement has been built on what might be called a Brown v. Board model of ministry. An assumption underlying this model is that proximity across lines of racial segregation is the goal of multiethnic ministry. Reflecting on the trauma experienced by the Black students who integrated white, hostile schools, Hurston asks, “Can such a degrading experience be gloated over as ‘advancement’? Yes, if more physical contact can be regarded as the ultimate goal and ideal. No, and emphatically no, if my own dignity and self-respect are taken into account.”

The traumas experienced by some people of color in intentionally multiethnic churches aren’t as obvious as the violence associated with school desegregation. Yet research has regularly shown the costs paid by these members for the sake of relational reconciliation. (See, for example, Korie Edward’s The Elusive Dream or this article on the impact of multiethnic congregations on white people and people of color.) Though rarely identified so plainly, too many of our congregations act as though success is realized by diversifying culturally white congregations with the presence of people of color.

This vision ignores the cost paid by those who, having left racially and culturally hospitable churches, are the evidence white people can point to of their racial reconciliation. Hurston, thinking again of those integrating students, asks, “Is the price regarded as cheap for the pleasure of bringing the White students and their parents to the place where they will eventually tolerate you in the same class-room? They too were expendable. The end, perhaps, justifies the means. What price proximity?”

I fear that many of our multiethnic churches, by assuming that people of color will assimilate to white cultural norms and practices, have treated these members as expendable. The ends of multiethnic diversity and racial reconciliation have justified the means of assimilation, appropriation, and, at times, exploitation.

Bell, imagining an alternative to Brown v. Board, writes that rather than forcing integration, “we should concentrate on desegregating the money.” I take this to mean that, instead of assuming that Black people need to be proximate to white people for their success and well-being, the focus should have been on the material causes and impacts of racism under which African American citizens have always endured. That is, instead of seeing school integration as de facto evidence of racial justice, efforts should have been directed toward ensuring that Black people had the same access to material resources as their white neighbors, regardless of their proximity to those neighbors.

Despite the failures of the multiethnic church movement, I still believe that Christians have a particular call to reconciliation as evidence of the gospel’s power. This is, of course, different than the kind of societal racial integration that Bell and Hurston were grappling with. But their critique – that legislated integration which didn't address material equality often harmed Black people and their institutions – is one multiethnic churches must seriously consider. Are our reconciliation efforts mostly about the kind of proximity which upholds white cultural dominance while assuming the assimilation of people of color? Or are we willing to imagine something different?

That different would ask this question: Is this multiethnic church good for Black people and other people of color? And by good, we would imagine a holistic good which includes the spiritual, emotional, physical, and financial goods historically nurtured by African American congregations. (Everything I’ve written so far can be read as an apologetic for Black churches and other culturally conscious congregations which refuse the lie that proximity to whiteness is evidence of advancement of any sort.) A multiethnic church which prioritizes the holistic good of its Black members does so not as an act of charity – never that! – but as a way to deal truthfully with the exploitative racial status quo. It is to refute the promises of whiteness with the truth of God’s all-encompassing shalom.

(Photo credit: O'Halloran, Thomas J. O'Halloran.)