Loving Opposition

Henri Nouwen, MLK's principles of nonviolence, and community-building confrontation.

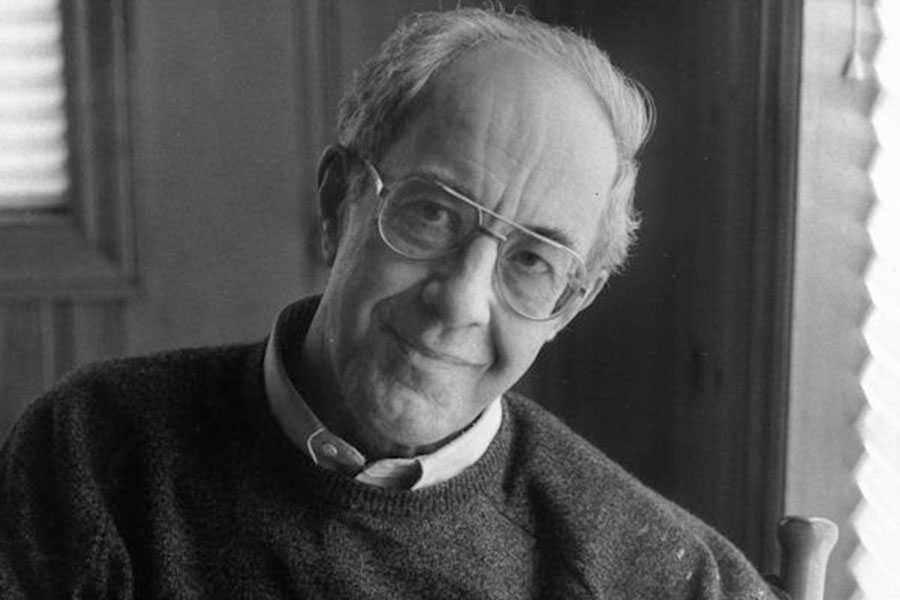

In 1989, Henri Nouwen, the Catholic priest, author, and academic, published a series of talks he gave on the topic of Christian leadership in the twenty-first century. In the decades since, In the Name of Jesus has become one of those rare classics which continually crosses Christianity's typical silos. I'm rereading it slowly with one of our church's leaders and finding Nouwen's insight to be as illuminating today as it must have been to those who first heard his lectures.

For those who haven't read this small book, Nouwen organized each of its three sections as movements- from relevance to prayer, from popularity to ministry, and from leading to being led. Nouwen had recently left a position at Harvard for L'Arche in order to practice ministry among the mentally handicapped, "men and women who had few or no words and were considered, at best, marginal to the needs of our society." It was from his place among this new community that he approached the theme of leadership.

Each of the three movements is structured by a temptation, a question, and a discipline. So, the first movement, from relevance to prayer, features the temptation to be relevant; the question, Do you love me?; and the discipline of contemplative prayer.

Nouwen is concerned that Christian leaders are succumbing to the temptation to be relevant to a society whose values are at cross-currents with those of Christ. He writes, "While efficiency and control are the great aspirations of our society, the loneliness, isolation, lack of friendship and intimacy, broken relationships, boredom, feelings of emptiness and depression, and a deep sense of uselessness fill the hearts of millions of people in our success-oriented world." To enter into "deep solidarity with the anguish underlying the glitter of success," Christian leaders "will be those who dare to claim their irrelevance in the contemporary as a divine vocation."

Nouwen borrows his question from Jesus' post-resurrection query of the disgraced Peter, "Do you love me?" This is a question Christian leaders will repeatedly hear themselves being asked by their Savior. It is not a question about productivity or accomplishment. It cannot be answered with metrics or data. It is a profoundly relational question, one that pulls us from the isolation Nouwen believed defines contemporary society. To love Jesus is to know Jesus' love for us and "when we live in the world with that knowledge, we cannot do other than bring healing, reconciliation, new life, and hope wherever we go."

This week I had lunch with a Christian leader, well-known in our city for his quiet faithfulness and collaboration with diverse networks of pastors, non-profit leaders, and others. He told me about a three-year cohort of leaders he has organized. The first year focuses on the character of the leader. Only after twelve months exploring intimacy with Christ and spiritual fruitfulness do they move to the nuts-and-bolts of ministry. Like Nouwen, this leader understands that, more than anything else, Christian leadership is bringing an experience of the transforming love of God everywhere we go.

To be the sort of person who can continue to hear Jesus' question, Do you love me?, Nouwen offers the discipline of contemplative prayer. By this, he means the choice to "dwell in God's presence, to listen to God's voice, to look at God's beauty, to touch God's incarnate Word, and to taste fully God's infinite goodness."

While his vision is distinctly and self-consciously mystical, Nouwen has in mind the very this-worldly scenarios Christian leaders face which further our society's relational splintering. He writes that words like "'right-wing,' 'reactionary,' 'conservative,' and 'left-wing' are used to describe people's opinions, and many discussions then seem more like political battles for power than spiritual searches for the truth."

Consider the last time you overheard someone deploying this sort of categorizing language, maybe in person, on cable news, or scrolling social media. Was there any meaningful search for deep, spiritual truth in that moment? Or, more likely, was language used in a manner which designated insiders and outsiders, allies and enemies, the enlightened and the ignorant? Once such crude categories are outlined, the quest for power can be consolidated, justified, and leveraged against our enemies.

Our access to so much information from around the world means Christian leaders are under increasing pressure to form and articulate opinions about situations far beyond our embodied experience. This isn't all bad, but it can have the effect of arranging allegiances around personal positions. Soon, if we are not reflective, our identity and purpose creeps from our love for Christ to our partisan passions and ideological priorities.

This shift can only lead to division. "Dealing with burning issues," writes Nouwen, without being rooted in a deep personal relationship with God easily leads to divisiveness because, before we know it, our sense of self is caught up in our opinion about a given subject." Nouwen's insight is profound. So often the charge of divisiveness is leveled against those who speak against injustices in the world or, even more so, about our churches' complicity with inequity. Labeling the truth as divisive allows the beneficiaries of a rotten status quo to protect their power in the name of unity.

Nouwen understands divisiveness differently. For him, divisions among Christians don't result from speaking truthfully but from finding identity in anything other than the love of God. Divisiveness diverges from difference in that it is rooted in opinion and ideology.

To illustrate this distinction, we can imagine two different Christians who both believe former President Trump and the MAGA movement present a threat to democracy and to our vulnerable neighbors. Both are willing to speak directly and publicly about their opposition to this movement and to articulate why their Christian faith compels them to oppose its aims.

What differentiates these two Christians is that the first, let's call him Bob, has found his identity in a certain partisan identity while the other, Melody, remains contemplatively rooted in Christ's love. Because he understands himself by way of the politics he opposes, Bob finds himself unable to associate with those on the other side of the partisan spectrum. They are, inherently, his enemies. Bob is interested in consolidating power to defeat or, at least, diminish his ideological opposites.

On the other hand, while holding just as strongly to her conviction that the former president and his movement are a threat worth opposing, Melody is able to move toward those who believe differently. By abiding in Christ's love as the source of her identity, she is able to do what seems increasingly impossible in our polarized age: oppose her neighbors' ideology because she loves them. It is this loving impulse which orients Melody's opposition toward community rather than division.

We can see the real-world implications of this sort of contemplative prayer in at least of three of Dr. King's six principles of nonviolence: nonviolence seeks to win friendship and understanding; nonviolence seeks to defeat injustice, or evil, not people; and nonviolence chooses love instead of hate. King was explicit that the goal of the nonviolent movement "must be the creation of the beloved community."

King's abiding connection to the love of God animated blunt, public, and confrontational opposition to systems of racial supremacy and their representatives. But that same abiding love provided a platform for, as he said, "redemption and reconciliation." Behind the sit-ins, mass arrests, and political agitation lay the knowledge and experience of God's love which extended to white supremacists and segregationists the invitation to a righteous and repairing relationships.

In 1989, Nouwen looked into the next millennium and imagined Christian leaders whose commitments to ideological relevance fostered divisiveness, inside of the church and out. Evidence of the accuracy of his prediction is all around us. But, despite too few examples of those who've accepted it, the invitation remains. "I am deeply convinced," wrote Nouwen,"that the Christian leader of the future is called to be completely irrelevant and to stand in this world with nothing to offer but his or her own vulnerable self. This is the way Jesus came to reveal God's love."

Reading

I mentioned the principles of nonviolence above. I recently finished Jonathan Eig's new biography about King and can't recommend it highly enough. Last week I read Dennis Edwards's new book about humility and talk about timely! I can think of a handful of public, opinionated Christians who'd benefit from shutting themselves up in a room for a week with this book. Others I recently finished: You Don’t Know Us Negroes by Zora Neale Hurston, They Flew by Carlos Eire (wonderfully weird in the way that well-written history ought to be), and Markings by Dag Hammarsjöld. I just picked up Libéte: A Haitian Anthology in the hope of better understanding what's happening in Haiti.

The View from Here

The Greater Bronzeville Community Action Council is a neighborhood organization I've participated in for over a decade. Our focus is supporting all the schools in our geographic footprint and this past Monday we invited our elected officials - state senators and representatives, city aldermen, etc. - to take questions about what they're doing to support out students. Watching families, educators, and community stakeholders repeatedly show up to advocate for our schools is incredibly inspiring.