Living in the Aftermath of Theft

Learning to interpret a world organized by plunder.

One of the through lines in my new book is how thoroughly theft, on a massive scale, has organized the world. More specifically I show how systems of plunder, and the greed and covetousness behind them, form a network of tangled roots which link racial and environmental injustice. It's the sort of thing that can sound pretty abstract until you start to see it. And then you can't stop seeing the pervasiveness and power of theft.

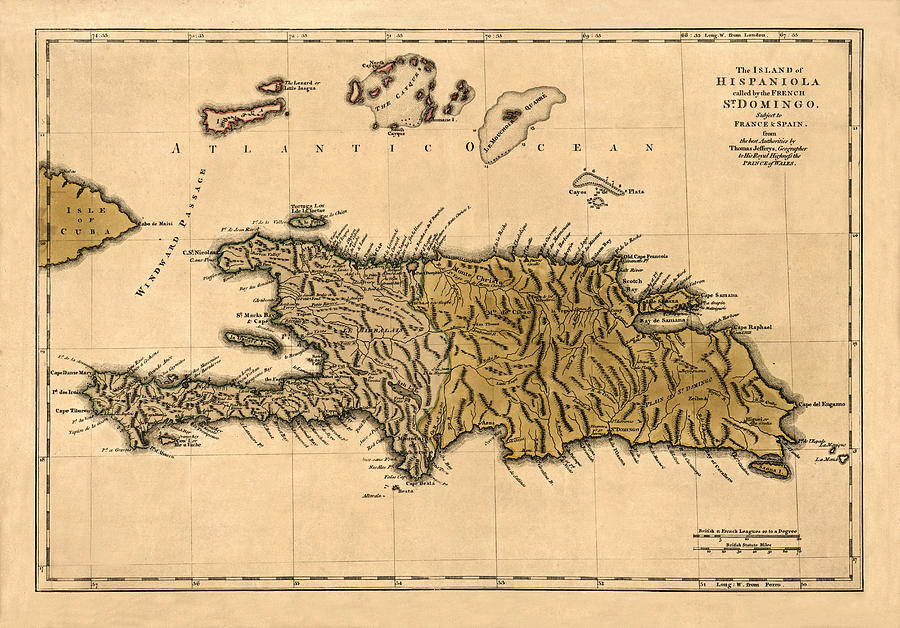

Take, for example, this anthology about Haiti I'm slowly making my way through. Libéte collects different source documents about historical periods and cultural themes, told mostly from Haitian perspectives, to provide a more nuanced understanding of the island nation than we tend to get from the headlines. (I know that's not saying much but, despite that low bar, it's an excellent book.)

The collection begins with excerpts from Christopher Columbus' journal after first encountering the Tainos people on what came to be known as Hispaniola. Columbus was struck by the hospitality shown by the indigenous people to his crew, noting that "they gave us water in gourds and clay pitchers like those in Castille, and brought us everything they had and thought we wanted, all with wonderful openness and gladness of heart." He goes on to say that he'd never "met a people so good-hearted and generous, so gentle that they did their utmost to give us everything they had."

Columbus also anticipated those who might dispute the Tainos' generosity, saying that what they gave "was of little value," by noting that "those who gave us pieces of gold gave as gladly and willingly as those who gave us gourds of water."

On his return voyage, Columbus met this generosity with a letter from King Ferdinand. Among other things, this letter informed the Tainos that the "late Pope gave these islands and mainland of the ocean and the contents hereof to the above-mentioned King and Queen... Therefore, the Their Highnesses are lords and masters of this land." Should the island's inhabitants refuse to recognize "the King and Queen of Spain as rulers of this land," the letter went on to threaten the Tainos severely: we "shall enslave your persons, wives and sons, sell you or dispose of you as the King sees fit; we shall seize your possessions and harm you as much as we can."

Writing about these early years of colonization, Haitian political scientist Benoît Joachim identifies the motivations of the European explorers. "The Conquistadors had not crossed the ocean in order to put down roots in the Indies in general, and Haiti in particular." Their aim, rather, was to "help themselves to new riches – principally gold – and take them to Europe, even if it meant converting these pagans, who stood between them and the coveted riches." Having quickly exhausted the island's gold mines, "the Conquistadors abandoned it almost completely."

As time passed, the Spanish and then the French began importing kidnapped and enslaved Africans to work the Haitian plantations. The Trinidadian historian C.L.R. James writes about the staggering wealth that was extracted from the land by this captive and brutalized labor force. "In 1767 [the colony] exported 72 million pounds' weight of raw sugar and 51 million pounds of white, a million pounds of indigo and two million pounds of cotton, and quantities hides, molasses, cocoa and rum." By means of the violent efficiency of the slave trade, "on no portion of the globe did its surface in proportion to its dimensions yield so much wealth as the colony of San Domingo."

The generous hospitality displayed by the Tainos is placed in sharp and grievous relief when contrasted with European theft. We don't need to appeal to vague idealizations of native cultures to see how thoroughly the colonial enterprise was powered by greed. In theologian Daniel Castillo's phrasing, Haiti has long existed as a zone of extraction, a site to be plundered and whose wealth is transferred to zones of accumulation. Though this narrative runs right up to the present moment of political turmoil on the island, it's a history that is typically forgotten for cruder, exculpatory explanations.

If we are ever to get to the truth behind our world's urgent crises, we'll need to learn to see how the pervasive influence of theft has constructed the contemporary world. Haiti may be one particularly painful expression of the power of systemic plunder but, for those with the care to notice, examples abound much closer to home.

Speaking of plunder, my new book now exists online and is available for pre-order.

I'm especially grateful for the endorsements from friends and colleagues that are beginning to trickle in. This one, from Randy Woodley, is especially meaningful to me.

The West has segmented life into small compartments to the point where few people actually live a whole existence. In Plundered, David Swanson presents us with all the right ingredients: humanity's purpose and our relationship with creation, justice, race, economics, sabbath, and virtue. This book was made to put us back together again and show us how to understand life the way it was meant to be.

The View From Here