Just how much racism is in our DNA?

This week I learned that there's something called the World Socialist Website and that they published an interesting interview with James McPherson who's book about the Civil War is exceptionally good. Anyway, the interview is ostensibly about The New York Times' recently published 1619 Project and it quickly becomes clear that neither McPherson or his interviewer are all that impressed with it. I've not read all of the 1619 articles but what I've read - and the podcast episodes I've listened to - have been well done and informative, so I was interested in McPherson's critique.

Some of you might be interested in the whole thing, but here's the portion of the interview that jumped out to me.

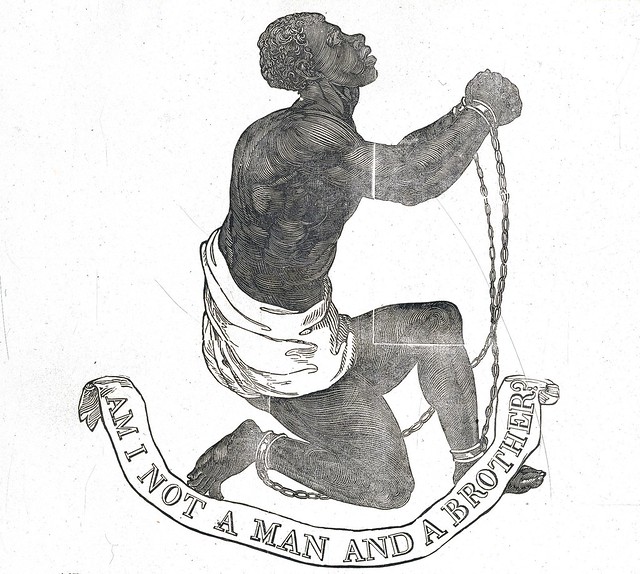

Q. Nikole Hannah-Jones, the lead writer and leader of the 1619 Project, includes a statement in her essay—and I would say that this is the thesis of the project—that “anti-black racism runs in the very DNA of this country.”

A. Yes, I saw that too. It does not make very much sense to me. I suppose she’s using DNA metaphorically. She argues that racism is the central theme of American history. It is certainly part of the history. But again, I think it lacks context, lacks perspective on the entire course of slavery and how slavery began and how slavery in the United States was hardly unique. And racial convictions, or “anti-other” convictions, have been central to many societies.

But the idea that racism is a permanent condition, well that’s just not true. And it also doesn’t account for the countervailing tendencies in American history as well. Because opposition to slavery, and opposition to racism, has also been an important theme in American history.

Q. Could you speak on this a little bit more? Because elsewhere in her essay, Hannah-Jones writes that “black Americans have fought back alone” to make America a democracy.

A. From the Quakers in the 18th century, on through the abolitionists in the antebellum, to the radical Republicans in the Civil War and Reconstruction, to the NAACP which was an interracial organization founded in 1909, down through the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, there have been a lot of whites who have fought against slavery and racial discrimination, and against racism. Almost from the beginning of American history that’s been true. And that’s what’s missing from this perspective.

McPherson, if I'm reading him correctly, takes issue with Hannah-Jones for a few reasons. First, he sees similar themes of racism in the histories of other societies. Second, he doesn't think that anti-black racism is the DNA of this country. And third, he sees certain white people like the Quakers as revealing that it's not only black people who've fought to make America truly a democracy.

I don't think his first concern deserves much of a response; I'm not sure anyone would disagree, including the contributors to the 1619 Project. (Having said that, it's interesting how often those who want to downplay the power of race and the persistence of racism bring up this sort of thing, as though the fact that there is racism in other countries somehow makes it less important. There's plenty to explore about what is distinct about American racism - the unique ways whiteness gets legally codified in the U.S.A., the tortured logic of the founders who had to square visions of liberty with their own enslaving tendencies - but we'll leave that for another day.) The second two, though, are worth exploring for what they reveal about the assumptions under-girding how we think about race.

Is racism a central theme to this nation's founding? McPherson thinks it is but also seems to believe that Hannah-Jones sees it as too central of a theme. This might seem like a quibble, but I actually think it's an important distinction. Over the years I've interacted with white people who are quick to acknowledge that racism is a part of the nation's history, but one that can be quantified and contained to certain moments and individuals. Once the claim is made, as the 1619 Project does repeatedly, that racism taints everything about the U.S.A.'s founding mythology, well, that's where the trouble starts.

In part, I think, this has to do with one's understanding of what racism is. For many it can be located in explicit actions or policies and, when it is, they have no trouble denouncing it. But the argument that people like Hannah-Jones are advancing is that racism functions more like a lens through which the world is viewed. This means that more of our shared history than just the obviously racist stuff has to be reckoned with through this lens.

This leads to McPherson's third concern which has to do with the exceptional white people who bravely stood against slavery. He's right about this, thankfully, though I'm not sure I'd characterize this as optimistically as he does: "there have been a lot of whites who have fought against slavery and racial discrimination, and against racism." Later in the interview he raises Abraham Lincoln up as an example. Yes, he admits, Lincolns views on race were complicated but he evolved over time.

Q. Is it correct to say that by the end of his life Lincoln had drawn to a position proximate to that of the Radical Republicans?

A. He was moving in that direction. In his last speech—it turned out to be his last speech—he came out in favor of qualified suffrage for freed slaves, those who could pass a literacy test and those who were veterans of the Union army.

But the important historical fact that Lincoln's views about African American people changed over time - during the war he lectured a delegation of black leaders about why it was the presence of black people which caused the war and why they'd need to emigrate to Africa after the war - doesn't mean that he shed his racist lens. One of the insights of David Blight's really good biography about Frederick Douglass is that it was very possible to be an earnest white abolitionist and still hold paternalistic and prejudiced assumptions about the very people you worked so hard to free.

So, to say that African American people, as those who've seen clearly the hypocrisies of the democracy, are the ones who've alone fought to hold the country to its promises is simply to notice how race has functioned. As Hannah-Jones writes, "More than any other group in this country’s history, we have served, generation after generation, in an overlooked but vital role: It is we who have been the perfecters of this democracy." This isn't to say that some white people haven't opposed racism and its many expressions - slavery, Jim Crow laws, lynching, mass incarceration, etc. - only that such righteous opposition does not free us completely from our captivity to, as Bryan Stevenson says, the narrative of racial difference. Lincoln could free the slaves and remain captive to this devious narrative.

This is all a long way of saying that how we think about racism - what we think it is - impacts significantly what we think an adequate response to racism is. Hannah-Jones and others are right, in my opinion, to think about race as a smog or an operating system or a strand of DNA. It's not our only story, but we cannot understand any of our shared story without reckoning with racism. And, for those of us who are white, there's actually quite a bit of freedom that comes from admitting our inability to keep this country's promises for liberty and justice on our own.

I have a hunch that Hannah-Jones would agree with McPherson's conviction that racism is not a permanent condition, or at least that it doesn't have to be. The really important question has to do with how we get there. It seems to me that confessing precisely the extent of the problem is the place to begin.

A couple of other related items for your weekend edification:

This article about a black church merging with a white church in North Carolina in The New York Review of Books takes a surprising turn toward the end.

Last summer I met Pastor Kevin Riley at a conference in Spokane. We've kept in touch and it was fun to be a guest on Kevin's podcast to talk about wading into the ministry of reconciliation as a white person.