Attention, Grief, and Love

On not looking away.

Hey! If you’ve read this newsletter for a while, you might remember that once a year I ask if you'll make a donation to the non-profit organization I lead through my participation in the Race Against Gun Violence. I’ll write more about this in the weeks to come but if you’ve appreciated my writing, would you please go ahead and donate here. Thanks!

In one of her essays collected in Vesper Flights, the writer and naturalist Helen Macdonald makes this sorrowful confession. She writes, “Increasingly, knowing your surroundings, recognizing the species of animals and plants around you, means opening yourself to constant grief.”

Reading this tender sentence brought me immediately to the entrance of the Bobolink Meadow in Jackson Park, a short walk from our apartment here in Chicago. A sign at the entrance informs visitors that the meadow was named for a bird that used to migrate through this area. Thankfully, bobolinks still inhabit much of the North American landscape, but their disappearance from our region is a loss I feel each time I enter the meadow.

Macdonald is acknowledging the personal risk of paying attention, the likelihood of heartbreak as we learn to see the impact of climate change on our local places or learn to hear the silence once filled with birdsong or learn to notice the obscuring light pollution that hinders our skyward gaze into the not-so-dark night.

Her observation can, I think, be applied more broadly. A newcomer to our church’s neighborhood might notice the many grass-filled open lots without wondering about their presence. Like me, they will be prone to miss the history behind these recently empty spaces, blocks which used to hold apartment buildings full of neighbors. They’re mostly gone now, casualties of the city’s regularly shifting public housing policies. Former residents, having been scattered far and wide, still gather for summer reunions in nearby parks, remembering the former days.

To know your surroundings, to attend affectionately to your community, is to expose yourself to grief. Not only grief, of course; we learn to see weather and neighbors, migration and culture such that gratitude is the only reasonable response. But also, as our attention is refined, we will be able to see the subtle and slow losses we’d previously missed. How neighborhoods have been rearranged by the force of racialized power. How aquifers have been depleted and watersheds drained by industrialized farming. How partisan binaries claim the allegiances of people whose realities are increasingly mitigated by screens.

This must be one of the reasons why friends and neighbors who once shared our attentiveness have, over time, allowed their interest to be diverted. It’s hard to keep looking, to keep grieving. There is a sort of numbing comfort that comes with allowing our attention to creep beyond our placed particularity to something else. There’s always another show to watch, another online partisan fight to engage, another child’s extracurricular to organize, another vacation to plan, another glittering thing to buy. The responsibilities and desires which used to intermingle with a lived obligation to our place and its people now take up most of our time. The stories we tell about attending with love to our places are told mostly in the past tense.

How, then, de we keep looking, knowing, recognizing? It begins with admitting that the grief which accompanies attention is not an experience distinct or distant from hope. In fact, it seems it is those who’ve most distracted themselves who are most prone to despair. Separating ourselves from the sadness that comes from recognizing the absence of one migrating bird also insulates us from joyfully welcoming so many other winged visitors. Pulling away from exploited communities also distances us from the endurance and resilience common among these neighbors.

The stakes are higher for Christians, who expect to find the presence of Christ among the hungry and thirsty, the estranged and imprisoned. It’s not simply that our hope is rekindled as we attend to the specific griefs and joys common to our home places; we also find in these cracked communities the One through whom creation was made, through whom creation is held together.

Resist the instinct to turn away from the grief in your community. It’s a gift received only by those with the love to see.

(Photo credit: Matthias Behr.)

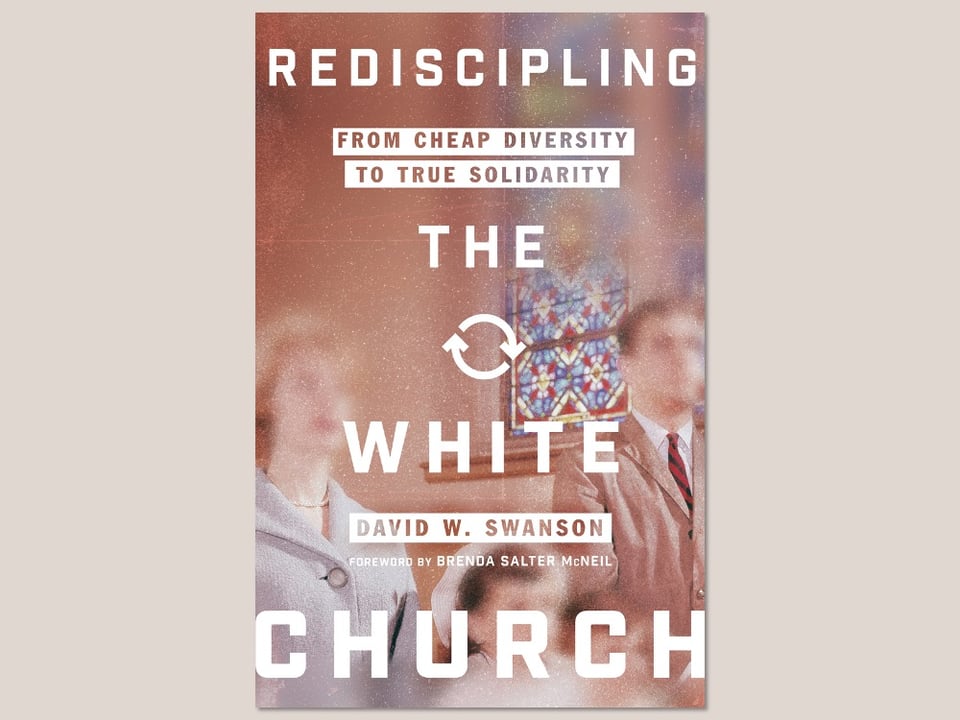

Rediscipling the White Church Four Years Later

Rediscipling the White Church was published four years ago and, in some ways, it feels like a book for this season. While many majority white churches have begun grappling with their role in the ministry of racial reconciliation and justice, others continue to abandon their people to the de-forming ideologies of our racialized and partisan society.

In addition to the book, you can download a free study guide and check out the video curriculum from Seminary Now.

Also, if you’re reading the book with your church or small group, I’d be happy to join your group via a video call for a conversation.

The View From Here