Scrolling through data

This issue is a continuation of the last, where we dove into learnings from our four days of data collection on our sensory experiences during meals.

Phase 1: Data collection

Day 1: texture

Day 2: color

Day 3: sound

Day 4: taste/smell

Phase 2: Data analysis

- Reflection

-

Data entry

-

Visual “scroll”

-

Sound or gesture data representation

Previously, we tackled textures and sound data collection through two phases in our analysis: reflection and data entry. Now we get to the more creative bit (finally!): the sensory scroll, which integrates all of the days of data collection, and sonifying the taste experience. We chose to represent our data through visual and auditory means rather than through taste or olfaction, for example, because the latter poses challenges in a newsletter format. Modern technology has yet to find a way to send a smell or taste via email. Until then…

Scrolling through the Senses

PROMPT: On a single, continuous sheet of paper (you may have to tape multiple pieces of paper together) make a continuous visual sequence (or scroll) that represents the data you collected. Your storyboard can have multiple layers, showing simultaneous properties of the data — whatever you think is relevant. (Adapted from the “Scroll” and “Landscape” activities in one of Arturo Cortez’s classes.)

Max

My scroll is really a grid with circles, two of my favorite graphic elements, where each circle represents the meal in question., Half-way through drawing, I realized I completely missed the point of “scrolling,” but as these are meant to be sketch-like, I kept going, noting ways that I could alter it into a scroll if I had not chosen an analog route (here’s where brief regrets of not using Procreate came in). Yet, we implement analog exercises wherever possible: these representations are meant to be sketches. Iterations, and perfection, are too tempting on the computer, with programs that allow for quick color changes, layers, and erasers that don’t leave an artifact on the paper, not to mention the technical ability required. Using pen and paper greatly reduced the time we spent on these exercises, with the added bonus of the tangible and visceral connection of working hands-on with the data.

This exercise nicely illustrates how metrics inform the shape of the data representation. As mentioned in the last issue, during the data entry phase, I created a separate tab for each data collection day, customizing metrics to suit the sense I was focusing on for that day. Consequently, the only commonality between each day was the meal number itself, which is nicely visualized in my ‘scroll’: four excel tabs → four columns, four meals → four rows on the scroll. A quick iteration I would have made right away if I had been sketching on my iPad would have been to make a horizontal scroll and have each circle take up the width of the page in a rectangular format so they sort of flow from one to another. I think this format would especially suit the first two days: textures and colors. I imagine that my pie chart might warp into a treemap, but I have no hard feelings about that.

Jordan

Explanation of the scroll’s structure: From left to right, each vertical column represents a meal or snack where I collected sensory data. From top to bottom, each row represents a different dimension of the data: an abstract doodle representing the sensory notes I took; a bar chart representing how accurately I felt my notes captured the sensory experience (on a scale from1 to 10); a colored segment indicating the type of meal; a pictogram of the food item; and a textured hash-mark indicating the location of the meal.

I let the materials I had at hand — leftover accordion paper that I had trimmed from blinds that I recently hung in my office windows — dictate the format of my scroll. My raw data had 32 food items, and my accordion paper had 66 pleats, so each food item took up two pleats of real estate.

Image of the scroll:

See it in action!

See it in action!

Notes Jordan jotted down right after creating the scroll:

Wow, that was a physically intense experience. It took a lot longer than I anticipated (about an hour and a half). My hands are now covered in ink smudges and my knees are a bit bruised -- but it was fun and worth it! I felt like I really got physically intimate with my data. I went BIG, mapping my data streams onto the remnants of paper blinds that I installed on my windows -- so my canvas was roughly 11 inches by 65 (??) inches.

The first stage was planning, and that involved deciding which data to include and how much space to allocate for each type of data. First, I counted the pleats in the canvas. Luckily, there were enough so that I could do two pleats for each data point (food item), with a few leftovers to have a legend on the end. Then, I had to divide the canvas horizontally for each type of data. I decided to include observations, how well the observation represented my experience, type of meal, item, and location. I tried to pick these fairly quickly and not spend too much time worrying about them.

For observations, this was the loosest, most abstract representation of the data. Since I love making doodles (I’m always doing them while listening to talks), I decided to make a free-form doodle inspired by the written observations that I took for each food experience. This was by FAR the easiest to do with texture -- those ideas just flowed out of me. And taste on its own was the hardest (both because I was tired upon reaching item 30, and I just had so little to go with.) Color and sound were somewhere in the middle, and the ease of being able to create a doodle depended on the detail of the description.

The scroll exercise marked the first sensory representation (visual) of our data, echoing the format of our data entry. Whereas Jordan’s scroll guides the viewer through her long datasheet, I split mine into 4 parts (one for each day of data collection), which is obvious in my portrayal of four columns with four circles. Furthermore, I didn’t consider my data to be static - for this exercise, and the following, I molded my data to fit the tool or representation I was depicting.

Sonifying Taste

PROMPT: Create a sequence of sounds or gestures that represent the data you collected. You can perform this live, or record it, or represent it as instructions for action (i.e. a score).

Max

When I began working on this exercise, I wasn’t satisfied with the format of the data I had previously entered. I transformed it to fit the data format I would need for my first (!!) sonification, which I created using twotone.io, a wonderful tool for sound sketching data.

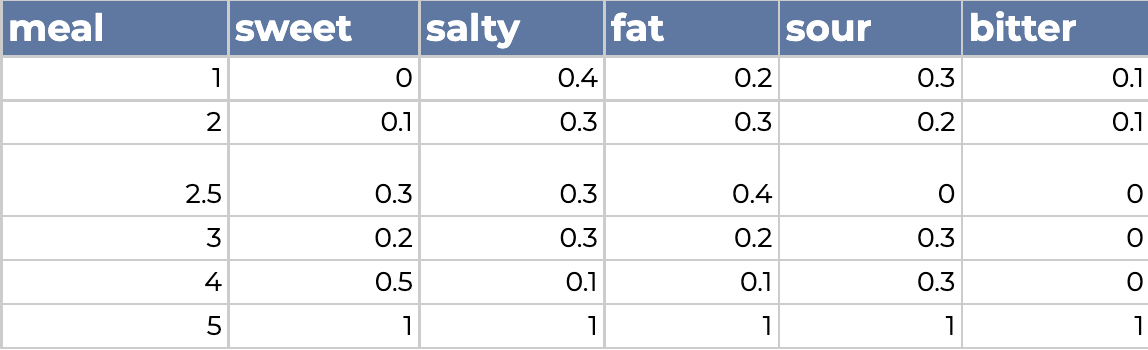

Like the day 4 pie charts from the previous exercise, each taste received a rough proportion of my perception of that taste in a given meal. Because TwoTone is a bit finicky with data and doesn’t naturally recognize proportions, I had to make a fifth phantom meal to tell it that 1 is the highest number any of them could theoretically reach (1 being 100%). This ensured that a sweet .3 (30% of total taste experience) would be just as loud as a sour .3. In each meal (the rows), these 5 tastes add up to 1, and their number reflects the proportion that I perceived to be present in a given meal.

So, in meal #1: 0% sweet, 40% salty, 20% fatty, 30% sour and 0% bitter.

I then assigned an instrument to each taste that I felt represented it best in the limited TwoTone instrument library, with a background piano as a counter for the meal in question. I already think of the tastes as a harmonious combination, so what better way to represent them than through their musical counterpart? Since I’m not too fond of bitter tastes (I make an exception for arugula when it’s on pizza), I assigned it the most somber instrument in the library. Unfortunately, tone.io doesn’t let you save sonifications, and I didn’t write down the mappings (which I’m ashamed to admit, as my academic background in biology taught me better!!), so its up to the listener to try to decipher the mappings themselves.

I set out knowing that neither this data nor this representation would be “true,” but that didn’t bother me - tastes are customized to our upbringing, culture, and experiences, so as long as this sonification sounded ‘right’ to me, I had succeeded in my representation.

Next steps: Jordan and I both agreed that this sound sketch was begging to be coupled with animation. Sounds can be more emotional and abstract, so I am drawn to the idea of pairing it with a visualization to guide the audience.

At the time of these exercises, Jordan was preparing for multiple work interview presentations and responsibly restrained herself from getting sucked into the exercise.

Bringing it Together

Sometimes I am so focused on the flavors of my foods, that I have a hard time focusing or bringing my awareness to what is going on around me. While this data collection was far too short to change or even notice many habits, it is a good taste for how intense, imperfect, frustrating, yet gratifying self-data collection can be.

Jordan: I already had this idea that there's this whole kind of range of sensory inputs that go into eating, and this, just like reinforced that even more so, I think it wasn't like new revelation it was just something that I kind of knew but didn't really think about. It really made me hone in on the importance of texture and sound and color and the environment I'm in, you know.

Max: Yea! For me, it was pretty similar. The exercise put words to my sensory eating experience, and so it was insightful in that way.

Jordan: I think that is important. The context is like the room that you're in at the time of day, like the mood that you're in if you're rushing from one place to another, like all of these things also mediate your sensory experiences.

References

Tools Used:

- TwoTone

- Google Sheets

- Pen & paper